Good Attrition, Bad Attrition for Software Engineers

What does “normal” attrition look like by the numbers, how should you adjust for it, and how can you get ahead of attrition?

Q: What does healthy and unhealthy attrition look like for software engineers and tech workers?

Attrition – the rate of employees leaving a company – is an important topic for any manager. When it comes to software engineers and tech workers, opportunities to work elsewhere are plentiful, so it’s only normal for attrition to be comparatively high.

Or is it?

I’ve talked with and gathered information from more than two dozen engineering managers working at various tech companies to get a sense of what they consider to be “good” and “bad” attrition numbers. I’ve also sat down with Dominic Jacquesson, who is VP of Talent at Index Ventures, and has advised dozens of portfolio companies on this topic. Dominic is the author of three (free-to-read online) books on startups, including Rewarding Talent: a guide to stock options for European entrepreneurs.

In this issue, we cover:

Attrition categories. Defining what we mean by attrition, and how to think about it.

Attrition numbers. What does “good” and “bad” attrition look like, based on the stage of the company? How is it different for engineering managers?

Adjustment factors. There are many things that can increase or reduce attrition. Some examples of these.

Events that increase and decrease attrition. From a forced return to the office to promoting before people are ready: how do events increase, decrease or delay attrition?

High and low attrition cases. And what were the causes?

Remote work and attrition. What’s the connection, and will remote work always be a differentiator?

Practices for getting ahead of attrition. What are approaches which can reduce attrition?

1. Attrition categories

Attrition means employees leaving their job at a company, which happens for a variety of reasons. People might quit. They might be let go for performance reasons. They might not make it through their probation. And there are other reasons. How do we measure all of this?

I turned to Dominic Jacquesson, as he has been observing this area for more than two decades; initially, as a COO (chief operations officer) at several companies, and for the past ten years as VP of Talent at Index Ventures, where he supports venture-funded startups from the seed stage, all the way to IPO. Here is the model Dominic uses to think about this space:

1. Involuntary attrition. This includes everyone who has not left on their own terms. It usually consists of:

People not passing probation. It’s expected some new hires will not work out and leave during, or at the end of, their probation. Dominic suggests if the probation pass rate is below 90%, this is a flag, and one that warrants investigation. At early-stage startups, Dominic advises it’s good practice to review how each hire works out, to calibrate the recruitment process.

Let go due to performance reasons. Those who are let go because their performance did not meet expectations, even after getting feedback and support.

Let go due to layoffs. If a company makes people redundant, this is termed involuntary attrition.

2. Voluntary attrition. This covers all cases when people leave of their own will. There are two separate buckets:

2.1. Regretted attrition. Dominic phrases this as “leavers whom it’s a shame are leaving”. I’d phrase this as people who the company would rehire with no additional interviews within the next 12 months. Basically, those who would be welcomed back, no questions asked.

2.2 Non-regretted attrition. Dominic described this as very easy to define when a company is small; just ask the question, as a founder: “do I regret this person leaving?” The answer is “yes” if the person in question was a good performer, or if they were an average – as in neither great nor poor – performer, but have skill sets which are difficult to hire for. Dominic also added that it’s not just about performance, but also about the values and behavior of the individual being aligned with the team and the company, and driving positive outcomes.

My definition of non-regretted attrition is that if you answer “no” to the question “can this person rejoin in the next 12 months without any interviews?” then they would be a non-regretted leaver. It means the individual does not have doors open to their return, most likely because they were either a poor performer, and / or had a negative impact on their team’s performance. Ideally, this person got this feedback before they left.

When talking about attrition, most companies focus on voluntary regretted attrition. But it’s important to track all types of attrition. However, non-voluntary attrition is the company’s decision and non-regretted attrition should ultimately be a positive. It is the voluntary, regretted attrition which hurts an employer, and is the type of attrition companies and teams will want to minimize.

When measuring attrition, Dominic suggests to look at this on an annualized basis using like-for-like measurements. Take the number of leavers at the beginning of the period, then see which % of those people count as voluntary attrition.

For example, 10% annual attrition means if there were 100 people 12 months ago, 10 of them have left since. Dominic suggests measuring attrition with various granularities to spot trends sooner.

Annual: the number of people who left in the past 12 months.

Quarterly: which % of people left during the past quarter voluntarily, and multiply it by four to get the annual number.

Monthly: look at the same for the past month and multiply it by 12. Monthly attrition can show scary numbers because of its high granularity. However, it can also forecast attrition problems bubbling up.

2. Attrition numbers

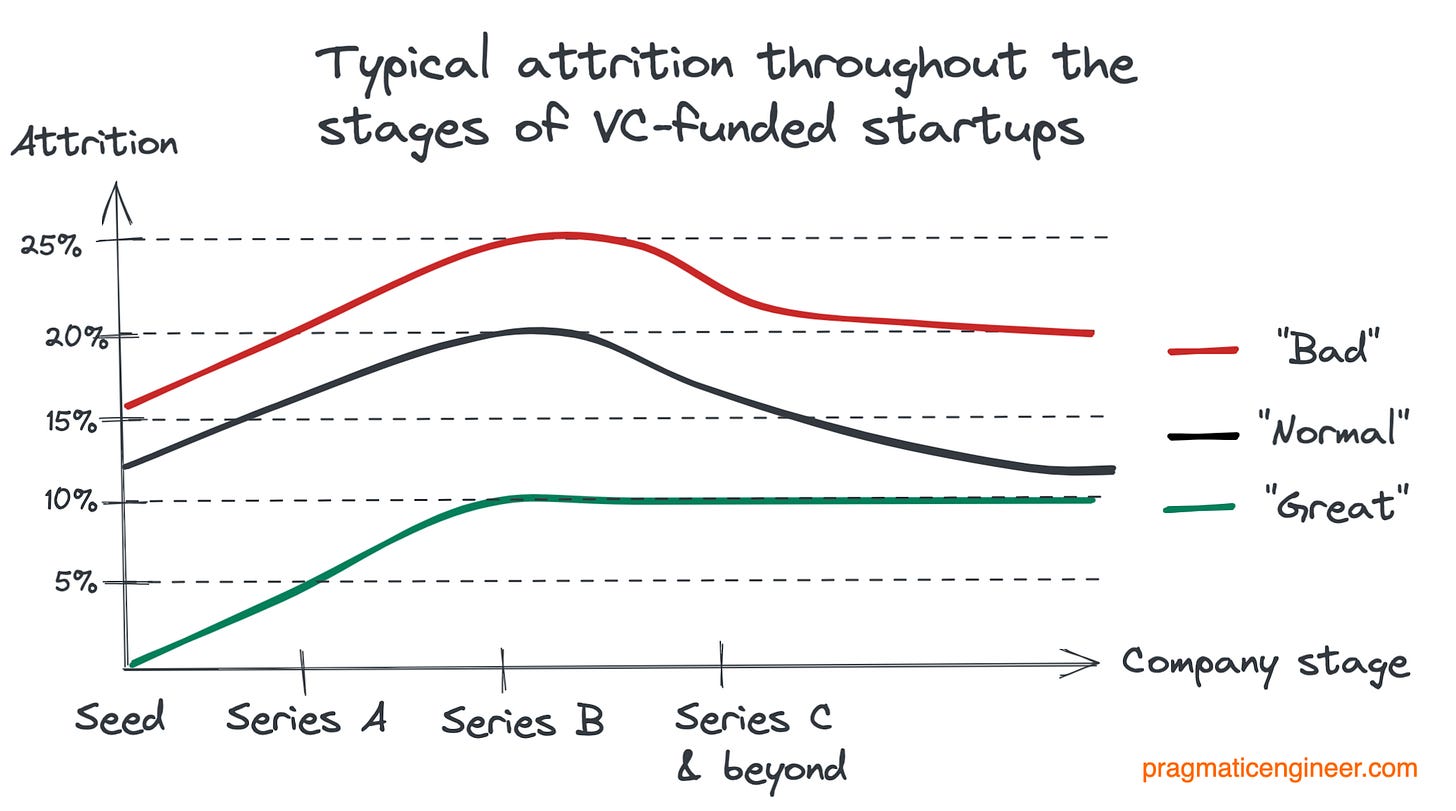

What are “great” and “bad” attrition numbers? After talking both with Dominic and more about 30 engineering managers, CTOs and founders, here are the most commonly cited numbers I found for “great”, “normal” and “bad” attrition.

The figures below are for annual voluntary attrition, including regretted and non-regretted attrition. Categories are separated by funding stage, and I add a category for developer agencies.

At seed stage, attrition is typically low. This is the point when a startup has funding secured, an exciting vision and a mission. Here’s what Dominic says about someone leaving at this point, reflecting the portfolio companies he assists:

“At seed stage, the best startups have no attrition. Every leaver is a cause of heartache and warrants a postmortem as to what happened. At this stage, while everyone reports to the founders, those founders run the show and they should know exactly what is happening.

At seed stage, it’s common to have a tight-knit group. It’s not uncommon to see 50% or more of hires come through the founders’ networks or via referrals. This is the stage set up for the lowest attrition. It will only get worse, as the company grows.”

At Series A stage, attrition starts to go up, and it typically peaks after Series B. This is what Dominic shares:

“As the company grows and middle management is hired, there will be more of a disconnect between the founders and many employees. Middle management can be viewed as a “necessary evil” at any growing company. This layer helps the company scale, but it also inevitably introduces “Chinese whispers” and potential disconnects between the values of the founders, and those actually exhibited by managers.

Attrition typically peaks during the Series B stage. This is the point when a company would expand rapidly, but it does not yet have the related talent acquisition and management processes in place, and those processes are not calibrated. You could call this stage a bit more messy than those before and after it, and this shows with attrition numbers.“Reaching Series B is also when the “family feel” disappears, and more early employees may leave with disillusionment, thinking "this place doesn't feel the same as it used to". At this stage, recruitment has typically not yet adapted and will often hire people who expect to work at a smaller startup, when they are by now joining a larger org.

As the company enters these later stages, it will have established processes to both hire and retain people, with the brand built up. By the time a company becomes a late-stage company or goes public, attrition will drop to around that of earlier stages.”

At publicly traded companies, attrition depends on many factors. Location and the business environment are two major ones. However, outside of locations where competition for talent is high, most of Big Tech plans for around 10% annual attrition during “normal” years.

This was certainly the case when I worked at Uber, where the European offices had around 10% – and sometimes less – engineering attrition in the period 2016-2019. The number was higher in locations like San Francisco where competition was greater and average tenure shorter than in most other offices.

Above 20% annual attrition is a cause for worry at almost all Big Tech companies. Such attrition can happen in exceptional years – for example, during the incredibly hot market of 2021 – and due to some of the adjustment factors we cover below.

Regretted attrition should normally not be above 6-8% during any of the stages, Dominic shares as insight. The attrition numbers above are for voluntary attrition which encompasses both regretted and non-regretted exits. In the phases when attrition spikes, it’s expected that non-regretted attrition increases, and regretted does not. Anything above 8% warrants a look into why people are quitting who are valuable to the business.

I expected developer agencies to have higher attrition than most other companies, but this turned out to not be the case. My thesis was that developer agencies typically cannot pay the top of the market as their cost structure doesn’t allow it. They also move people around to work on client tasks as the demand changes, and tend to hire less experienced engineers – even though the better ones do invest in people.

I talked with founders, CTOs and engineering managers at five developer agencies in Europe and India. Curiously enough, it was not the case that their attrition was outsized.

In the past five years, a large developer agency with more than 500 people in Ukraine saw 7% annual attrition during their best year, 10-11% in most years and 15-20% in the worst years. A UK consultancy with around 200 people that’s regularly targeted by Big Tech to hire from, saw 12% as the lowest (2020) and 26% as the highest over the past five years. An agency in India with around 30 people saw 10% in better years, 25% in worse years.

One sign of definite “bad” attrition at any company in a growth phase is more people leaving than being hired. This is why it’s useful to keep track of monthly or quarterly attrition.

A CTO at a scaleup with about 150 people shared how their leadership teams reviewed quarterly attrition numbers to get a pulse check of where things were. These were their numbers for three consecutive quarters in 2021, for the engineering team of around 60 people:

By the end of Q3, the trend was clear, and the attrition numbers showed no sign of slowing down. Even worse, the company could not keep up with backfilling attrition. Leadership also doubled down on learning the root causes of attrition and put mitigating measures in place as soon as possible.

I wish I could share they heroically turned the attrition around: this did not happen. However, with everyone aware of the problem, the CTO had data to prove the company needed to invest more in engineering; not just with compensation, but with realistic expectation setting, being far more flexible with remote work policies and catching burnout risks early.

3. Adjustment factors

Economic cycles have a large impact on attrition, predictably: