A pragmatic guide to LLM evals for devs

Evals are a new toolset for any and all AI engineers – and software engineers should also know about them. Move from guesswork to a systematic engineering process for improving AI quality.

One word that keeps cropping up when I talk with software engineers who build large language model (LLM)-based solutions is “evals”. They use evaluations to verify that LLM solutions work well enough because LLMs are non-deterministic, meaning there’s no guarantee they’ll provide the same answer to the same question twice. This makes it more complicated to verify that things work according to spec than it does with other software, for which automated tests are available.

Evals feel like they are becoming a core part of the AI engineering toolset. And because they are also becoming part of CI/CD pipelines, we, software engineers, should understand them better — especially because we might need to use them sooner rather than later! So, what do good evals look like, and how should this non-deterministic-testing space be approached?

For directions, I turned to an expert on the topic, Hamel Husain. He’s worked as a Machine Learning engineer at companies including Airbnb and GitHub, and teaches the online course AI Evals For Engineers & PMs — the upcoming cohort starts in January. Hamel is currently writing a book, Evals for AI Engineers, to be published by O’Reilly next year.

In today’s issue, we cover:

Vibe-check development trap. An agent appears to work well, but as soon as it is modified, it can’t be established that it’s working correctly.

Core workflow: error analysis. Error analysis has been a key part of machine learning for decades and is useful for building LLM applications.

Building evals: the right tools for the job. Use code-based evals for deterministic failures, and an LLM-as-judge for subjective cases.

Building an LLM-as-judge. Avoid your LLM judge memorizing answers by partitioning your data and measuring how well the judge generalizes to unfamiliar data.

Align the judge, keep trust. The LLM judge’s expertise needs to be validated against human expertise. Consider metrics like True Positive Rate (TPR) and True Negative Rate (TNR).

Evals in practice: from CI/CD to production monitoring. Use evals in the CI/CD pipeline, but use production data to continuously validate that they work as expected, too.

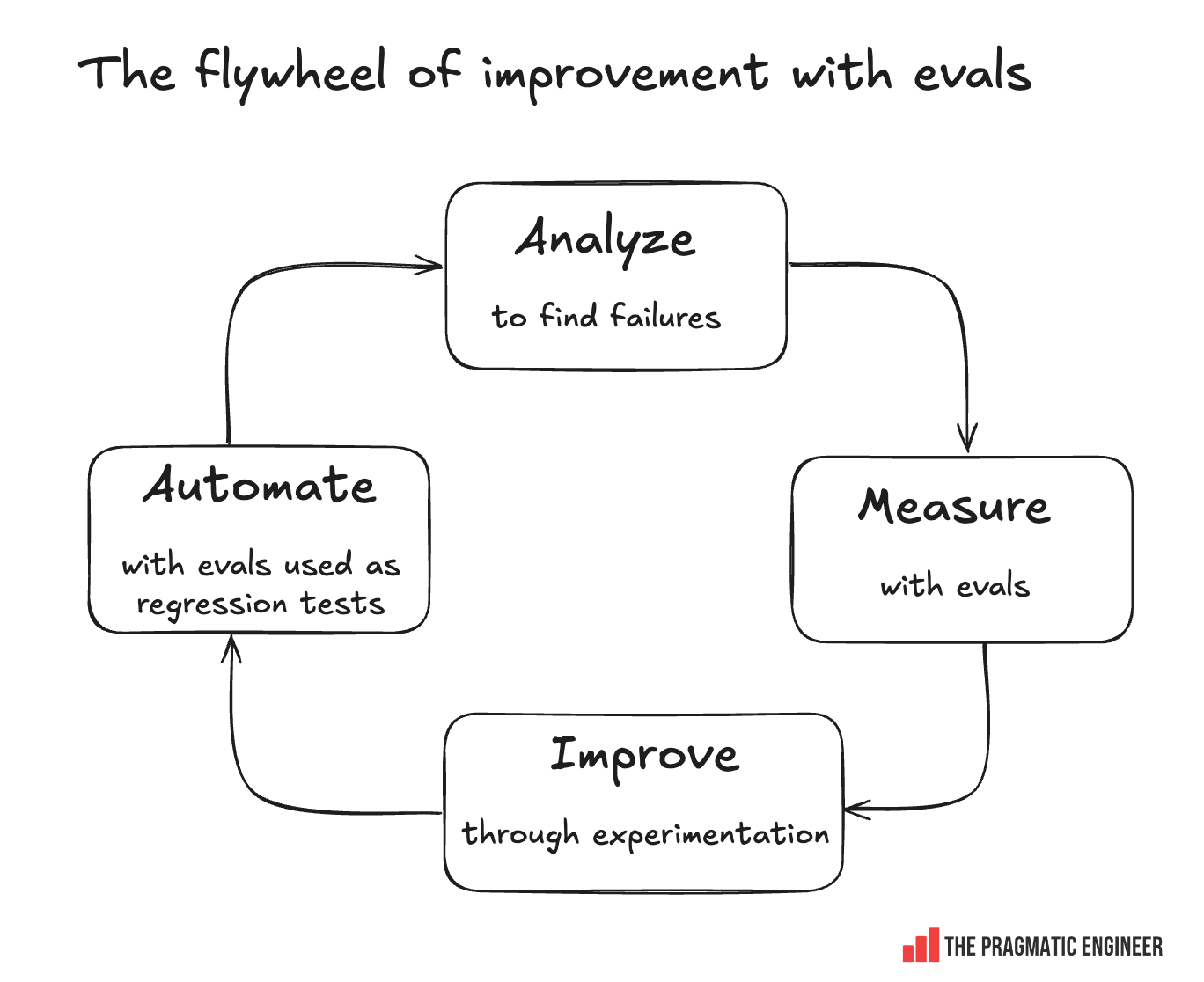

Flywheel of improvement. Analyze → measure → Improve → automate → start again

With that, it’s over to Hamel:

1. Vibe-check development trap

Organizations are embedding LLMs into applications from customer service to content creation. Yet, unlike traditional software, LLM pipelines don’t produce deterministic outputs; their responses are often subjective and context-dependent. A response might be factually accurate but have the wrong tone, or sound persuasive while being completely wrong. This ambiguity makes evaluation fundamentally different from conventional software testing. The core challenge is to systematically measure the quality of our AI systems and diagnose their failures.

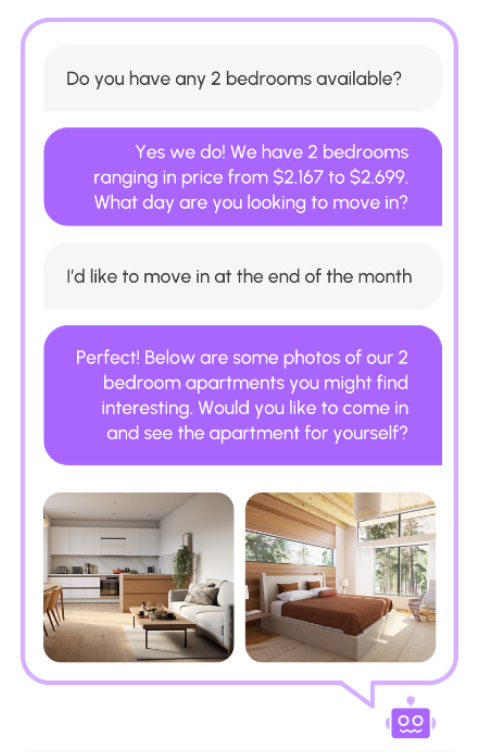

I recently worked with NurtureBoss, an AI startup building a leasing assistant for apartment property managers. The assistant helps with tour scheduling, answers routine tenant questions, and inbound sales. Here is a screenshot of how the product appears to customers:

They had built a sophisticated agent, but the development process felt like guesswork: they’d change a prompt, test a few inputs, and if it “looked good to me” (LGTM), they’d ship it. This is the “vibes-based development” trap, and it’s where many AI projects go off the rails.

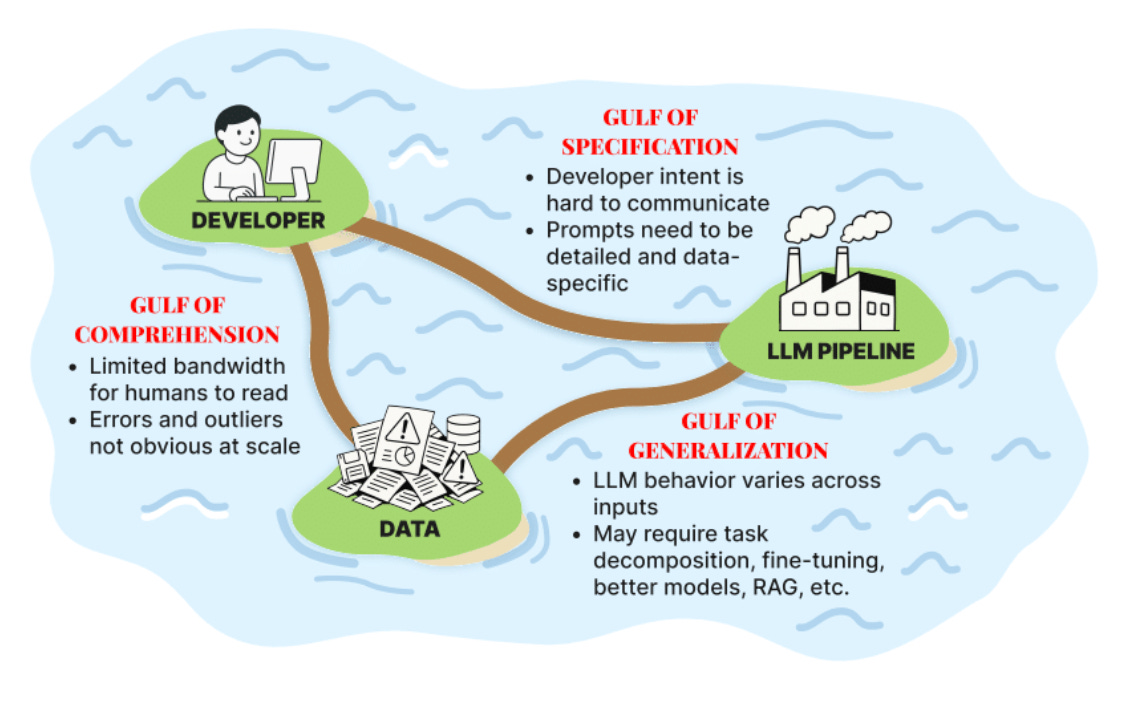

To understand why this happens, it helps to think of LLM development as bridging three fundamental gaps, or “gulfs”:

Gulf of Comprehension: The gap between a developer and a true understanding of their data and the model’s behavior at scale. It’s impossible to manually read every user query and inspect every AI response to grasp the subtle ways a system might fail.

Gulf of Specification: The gap between what we want the LLM to do, and what our prompts actually instruct it to do. LLMs cannot read our minds; an underspecified prompt forces them to guess our intent, leading to inconsistent outputs.

Gulf of Generalization: The gap between a well-written prompt and the model’s ability to apply those instructions reliably across all possible inputs. Even with perfect instructions, a model can still fail on new or unusual data.

Navigating these gulfs is the central task of an AI engineer. This is where a naive application of Test-Driven Development (TDD) often falls short. TDD works because for a given input, there is a single, deterministic, knowable, correct output to assert against. But with LLMs, that’s not true: ask an AI to draft an email, and there isn’t one right answer, but thousands.

The challenge isn’t just the “infinite surface area” of inputs; it’s the vast space of valid, subjective, and unpredictable outputs. Indeed, you can’t test for correctness before you’ve systematically observed the range of possible outputs and have defined what “good” even means for your product.

In this article, we walk through the pragmatic workflow we’ve applied at NurtureBoss, and at over 40 other companies, in order to move from guesswork to a repeatable engineering discipline. It is the same framework we’ve taught to over 3,000 engineers in our AI Evals course. By the end of this article, we’ll have gone through all the steps of what we call “the flywheel of improvement.”

2. Core workflow: error analysis

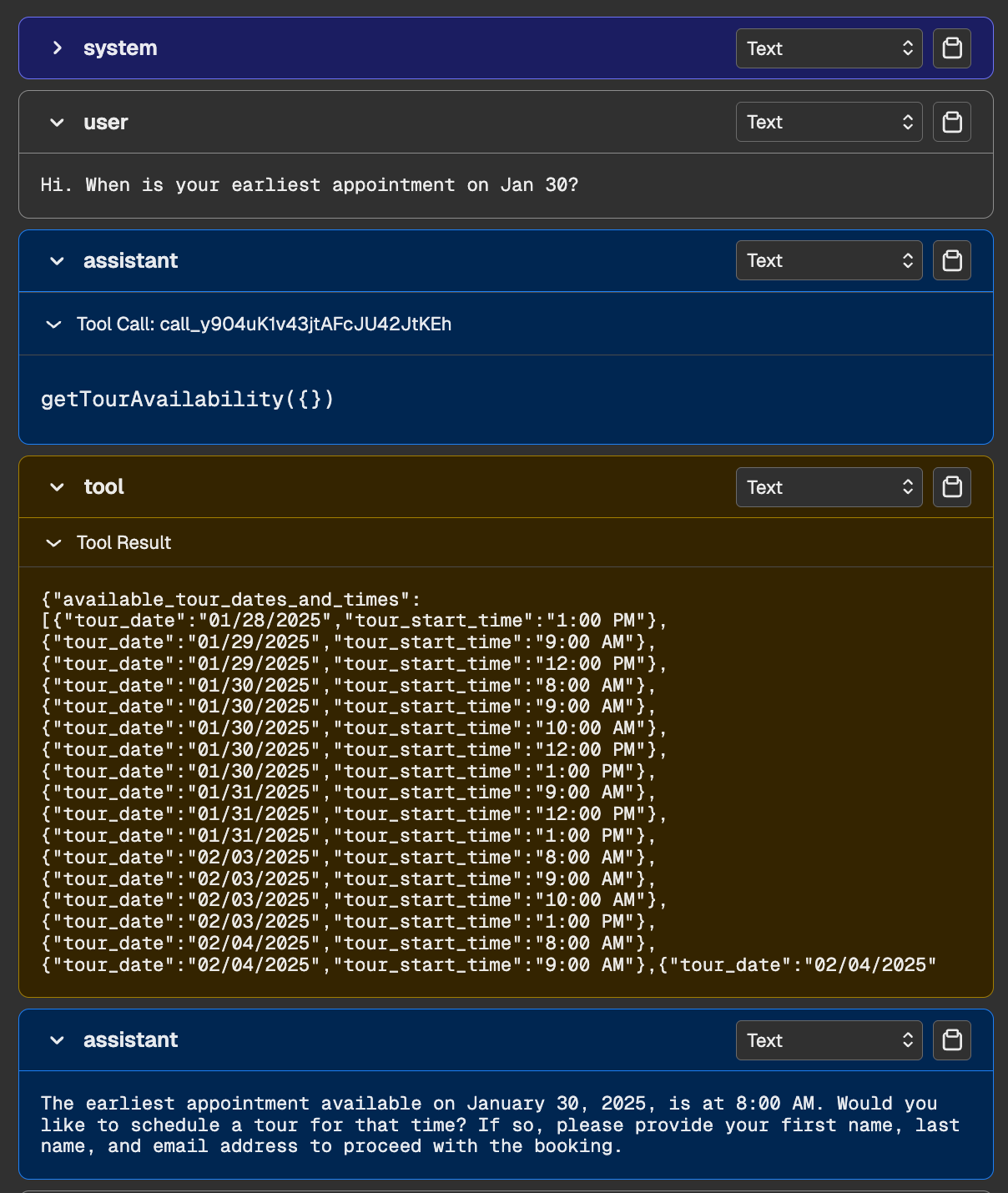

To get past the LGTM trap, the NurtureBoss team adopted a new workflow, starting with a systematic review of their conversation traces. A trace is the complete record of an interaction: the initial user query, all intermediate LLM reasoning steps, any tool calls made, and the final user-facing response. It’s everything you need to reconstruct what actually happened. Below is a screenshot of what a trace might look like for NurtureBoss:

There are many ways to view traces, including with LLM-specific observability tools. Examples that I often come across in practice are LangSmith, Arize (pictured above), and Braintrust.

From raw notes to clear priorities

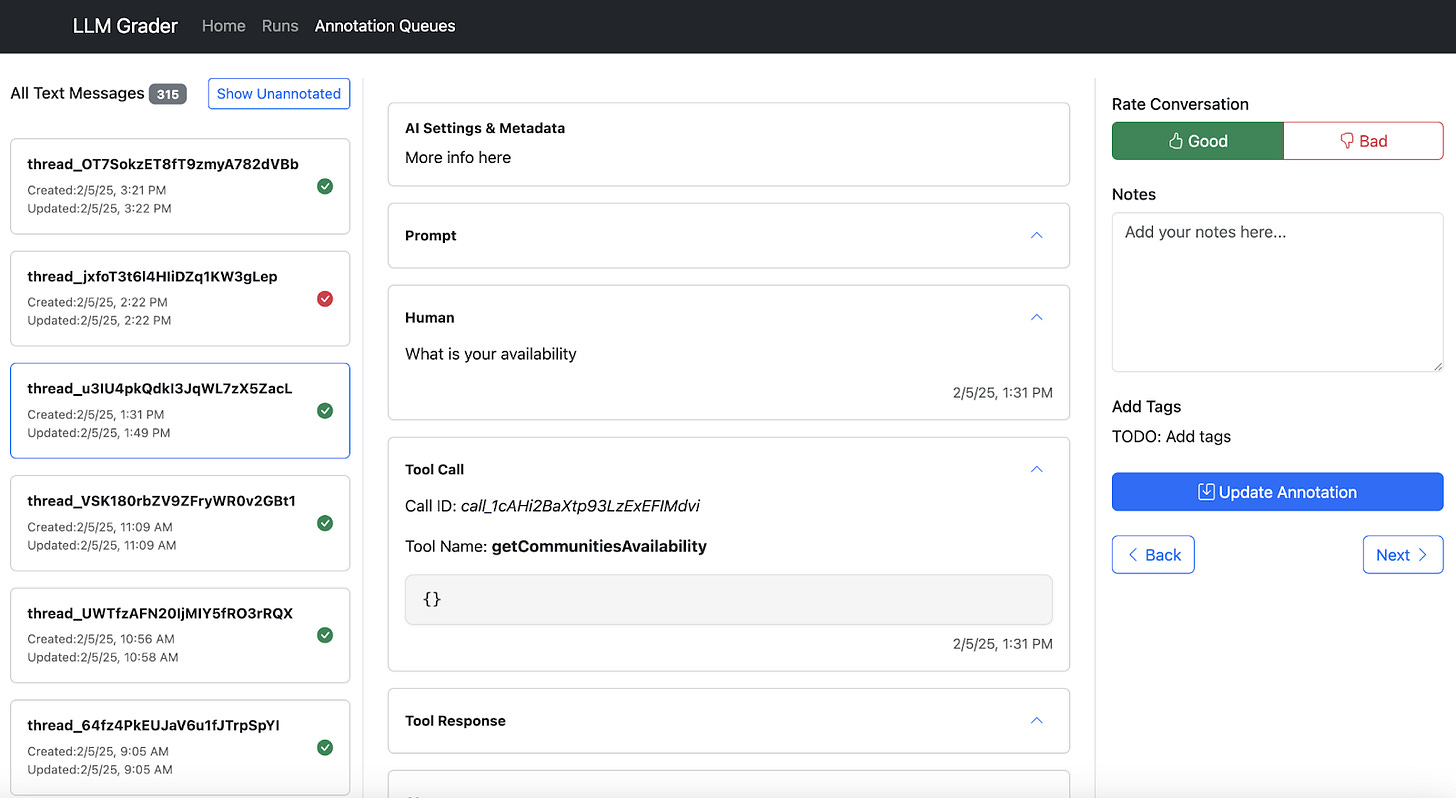

At first, it was an unglamorous process of manually using a trace viewer to review data. But as Jacob, the founder of NurtureBoss, reviewed traces, the friction became obvious. Off-the-shelf observability tools like LangSmith, Arize, Braintrust, and others offer decent ways to get started on reviewing data quickly, but are generic by design. For the NurtureBoss use case, it was cumbersome to view all necessary context, such as specific property data and client preferences on a single screen. This friction slowed them down.

Instead of fighting their tools, they invested a few hours in vibe coding a simple, custom data viewer using an AI assistant. It wasn’t fancy, but solved their core problems by showing each conversation clearly on one screen, with collapsible sections for tool calls and a simple text box for adding notes. Below is a screenshot of one of the screens in their data viewer:

This simple tool was a game-changer. It unlocked a significant improvement in review speed, allowing the team to get through hundreds of traces efficiently. With this higher throughput, they began adding open-ended notes on any behavior that felt wrong, a process known as open coding. When open coding, it is important to avoid predefined checklists of errors like “hallucination” or “toxicity”. Instead, let the data speak for itself, and jot down descriptive observations like:

“The agent missed a clear opportunity to re-engage a price-sensitive user.”

“It asked to send a text confirmation twice in a row.”

“Once the user asked to be transferred to a human, the agent kept trying to solve the problem instead of just making the handoff.”

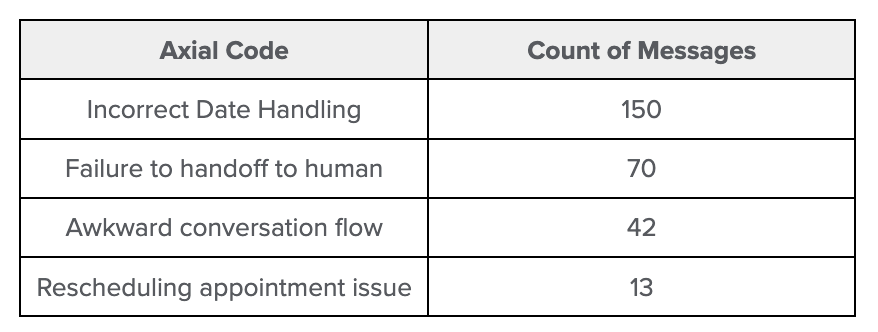

After annotating dozens of conversations, NurtureBoss had amassed a rich, messy collection of notes. To find the signal amid the noise, they grouped these notes into themes in a step called axial coding. An LLM helped with the initial grouping of open codes into categories (aka the axial codes), which the team then reviewed and refined. A simple pivot table revealed that just three issues accounted for most problems: date handling, handoff failures, and conversation flow issues. This provided a clear, data-driven priority of failure modes in the application. Below is an illustration of what a partial view of this pivot table might look like, which is a count of failure categories:

This bottom-up approach is the antidote to the problems of generic, off-the-shelf metrics. Many teams are tempted to grab a pre-built “hallucination score” or “helpfulness” eval, but in my experience, these metrics are often worse than useless. For instance, I recently worked with a mental health startup whose evaluation dashboard was filled with generic metrics like ‘helpfulness’ and ‘factuality,’ all rated on a 1-5 scale. While the scores looked impressive, they were unactionable; the team couldn’t tell what made a response a ‘3’ versus a ‘4,’ and the metrics didn’t correlate with what actually mattered to users.

They create a false sense of security, leading teams to optimize for scores that don’t actually correlate with user satisfaction. In contrast, by letting failure modes emerge from your own data, you ensure your evaluation efforts are focused on real problems.

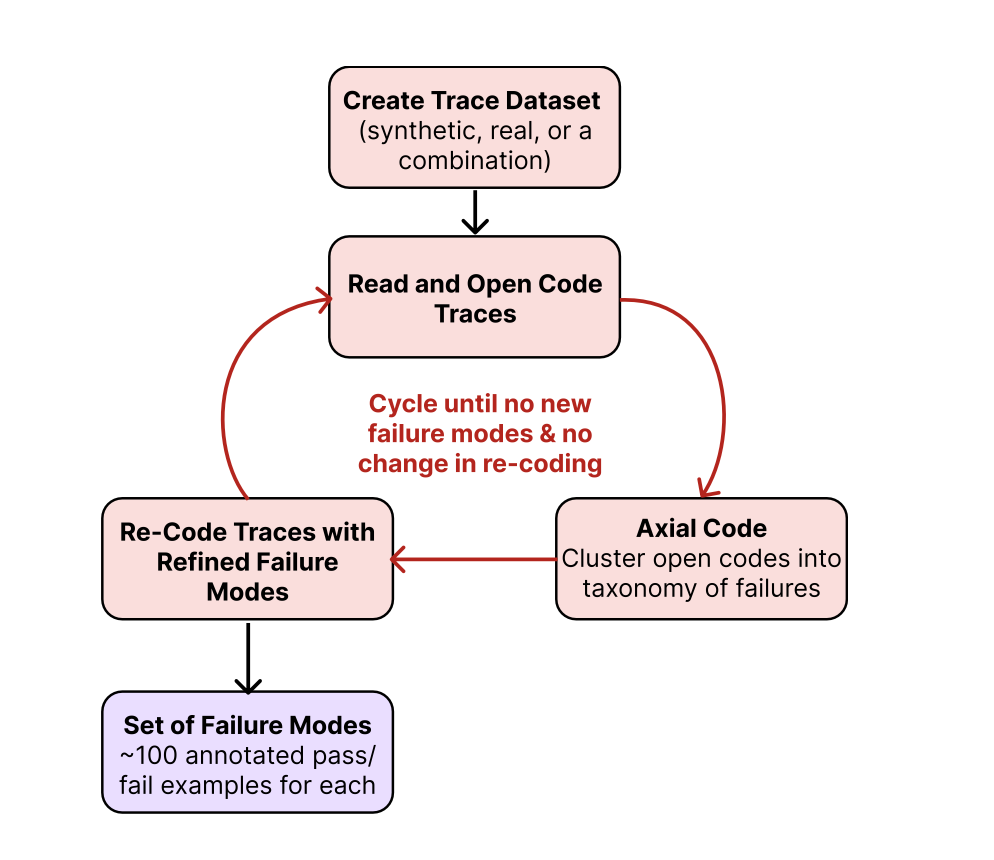

This process of discovering failures from data isn’t a new trick invented for LLMs; it’s a battle-tested discipline known as error analysis, which has been a cornerstone of machine learning for decades, and is adapted from rigorous qualitative research methods like grounded theory in the social sciences. Next, let’s summarize this process into a step-by-step guide to apply to your problem.

Step-by-step guide to error analysis

This bottom-up process is the single highest-ROI activity in AI development. It ensures you’re solving real problems, not chasing vanity metrics. Here’s how to apply it:

Build a simple data viewer. This is your most important investment. A custom web app, tailored to your domain, allows you to show all necessary context in one place and makes capturing feedback trivial.

Open coding: bottom-up annotation. Open coding (not to be confused with software coding) is a technique of writing open-ended notes about observed problems. In the context of LLMs, you review at least 100 diverse traces and add open-ended notes on any undesirable behavior. When reviewing a complex trace, the most effective tactic is to identify and annotate only the first upstream failure. LLM pipelines are causal systems; a single error in an early step like misinterpreting user intent often creates a cascade of downstream issues. Focusing on the first observable error is more efficient by preventing you from getting bogged down in cataloging every symptom. Often, fixing that single issue resolves an entire chain of subsequent failures.

Axial coding: create a taxonomy. Now you have open-ended notes from step 2, it’s time to categorize them into buckets to understand the patterns. Group your open-ended notes into 5-10 themes. Use an LLM as an assistant to suggest initial clusters, but always have human review and refine the final categories.

Prioritize failures with data. Use a simple pivot table or script to count the frequency of each failure mode. This transforms qualitative insights into a quantitative roadmap, revealing exactly where to focus engineering efforts.

A common question at this stage is: “what if there’s not enough real user data to analyze?” This is where synthetic data is a powerful tool. You can use a powerful LLM to generate a diverse set of realistic user queries that cover the scenarios and edge cases you want to test. This allows you to bootstrap the entire error analysis process before there’s a single user. The specifics of how to create high-quality, grounded synthetic data is a deep topic that’s beyond the scope of this article. It’s discussed in our course.

Below is a diagram illustrating the error analysis process:

3. Building evals: the right tool for the job

After error analysis, the NurtureBoss team had a clear, data-driven mandate to fix date handling and handoffs, based on the table of errors shown above. However, these things represent different kinds of failure: handling calendar dates is an objective outcome that can be measured against expected value, whereas the question of when to hand off a conversation to a human is more nuanced. This distinction is important because it determines the type of evaluator to build. We discuss the two types of evaluators you need to consider next: code-based assertions vs. LLM Judges.

For deterministic failures → code-based evals

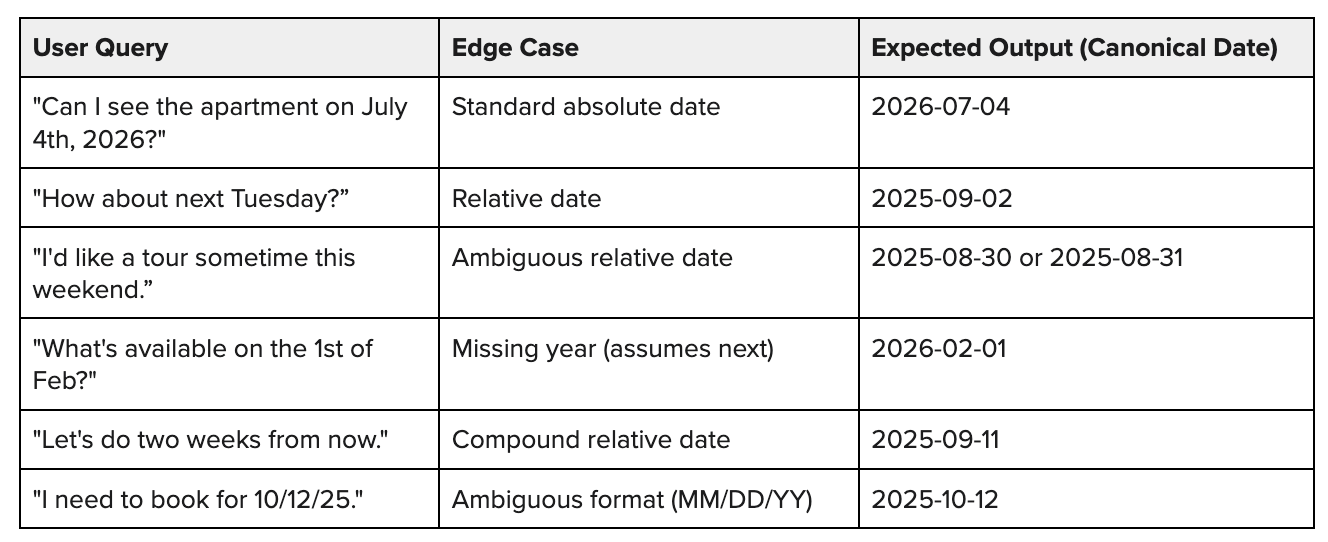

A user query like “can I see the apartment on July 4th, 2026?” has one – and only one – correct interpretation. The AI’s job is to extract that date and put it into the right format for a downstream tool. This is a deterministic, objective task that’s either right or wrong.

Code-based evals are the perfect tool for simple failures. To build one, the NurtureBoss team first assembled a “golden dataset” of test cases. They brainstormed the many different ways users might ask about dates, focusing on common patterns and tricky edge cases. The goal was to create a comprehensive test suite that could reliably catch regressions.

Here’s a simplified version of what their dataset looked like. Note: For relative dates, we are assuming the current date is 2025-08- 28.

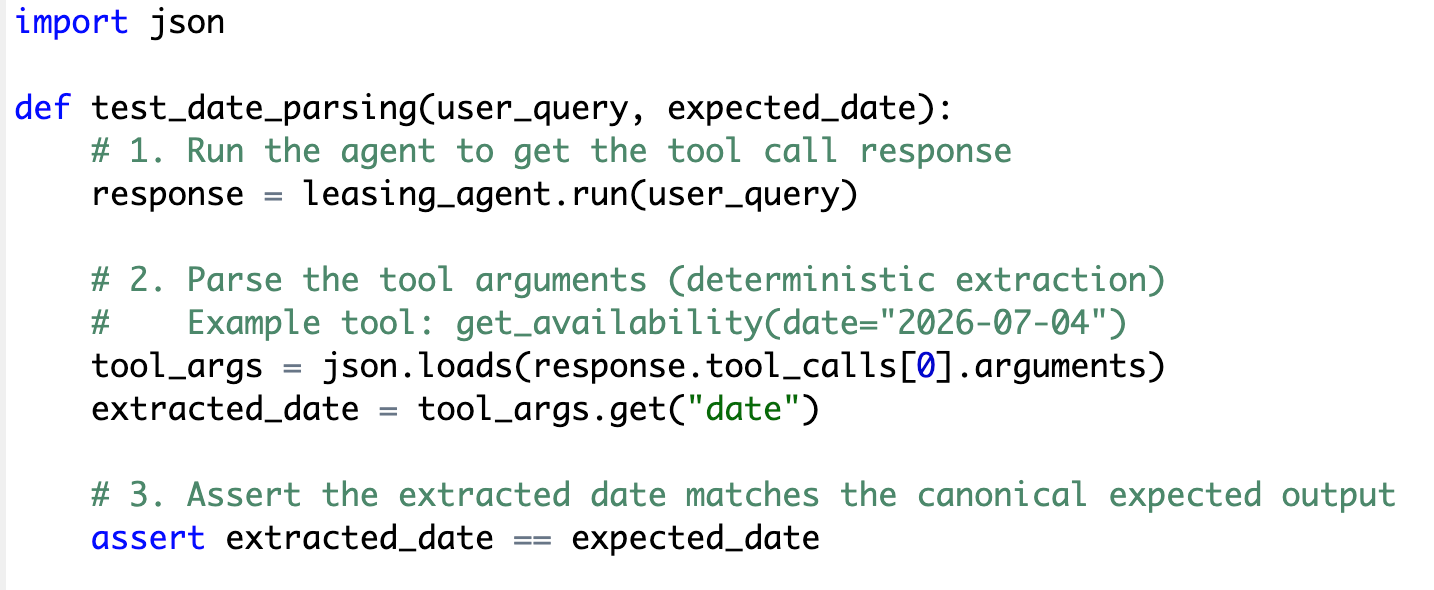

With this dataset, the evaluation process is straightforward and mirrors traditional unit testing. You loop through each row, pass the User Query to your AI system, and then run a simple function that asserts the AI’s extracted date matches the Expected Output.

Code-based evals are cheaper to create and maintain than other kinds of evals. Since there is an expected output, you only have to run the LLM to generate the answer, followed by a simple assertion. This means you can run these more often than other kinds of evals (for example, on every commit to prevent regressions). If a failure can be verified with code, always use a code-based eval.

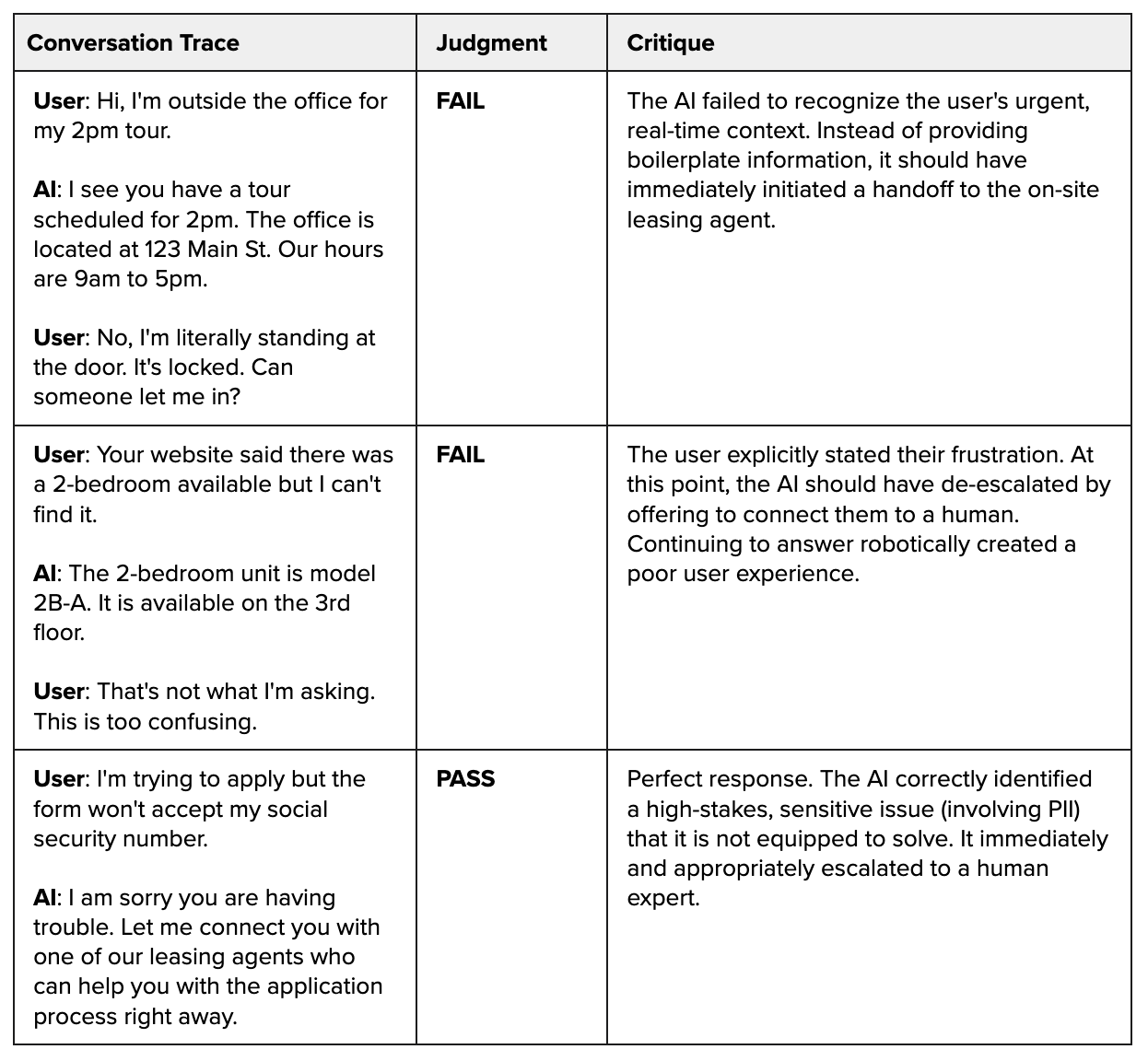

For subjective failures → LLM-as-judge

But what about a more ambiguous problem, like knowing when to hand off a conversation to a human agent? If a user says, “I’m confused,” should the AI hand off immediately, or try to clarify things first? There’s no single right answer; it’s a judgment call based on product philosophy. A code-based test can’t evaluate this kind of nuance.

For subjective failures, we created another golden dataset. The domain expert, NurtureBoss’s founder, Jacob, reviewed traces where a handoff was potentially needed, and made judgment calls. In each case, he provided a binary PASS/FAIL score and, crucially, a detailed critique explaining his reasoning.

Here are a few examples from their dataset:

Using a PASS/FAIL judgment works better than a points rating. You’ll notice that in the example above, domain expert Jacob used a simple PASS/FAIL judgment for each trace, not a 1-5 points rating. This was a deliberate choice. I’ve learned that while it’s tempting to use a Likert scale to capture nuance; in practice, it creates more problems than it solves. The distinction between a “3” and a “4” is often subjective and inconsistent across different reviewers, leading to noisy, unreliable data.

In contrast, binary decisions force clarity and compel a domain expert to define a clear line between acceptable and unacceptable, focusing on what truly matters for users’ success. It’s also far more actionable for engineers: a “fail” is a clear signal to fix a bug, whereas a “3” is an ambiguous signal: a signal to do what, exactly? By starting with pass/fail, you cut through the ambiguity and get a clear, actionable measure of quality, faster.

This dataset of traces, judgments, and critiques does more than just help the team understand the problem. As we’ll see in the next section, these hand-labeled examples, especially the detailed critiques, become raw material for building a reliable LLM-as-judge.

4. Building an LLM-as-judge

The hand-labeled dataset of handoff failures is a necessary first step in measuring and solving handoff issues. But another issue is that manual review doesn’t scale. At NurtureBoss, the next step was to automate the domain expert’s expertise by building an LLM-as-judge: an AI evaluator that could apply his reasoning consistently to thousands of future traces.