Navigating the individual contributor to engineering manager transition

The expectations of the role, your first year as an engineering manager (EM) and growing as an EM.

“Q: I’ve just been promoted to an engineering manager position. What are the things I should expect, and what can I do to make this transition a success?”

For this question, I feel Senior Engineering Manager at Spotify Diego Ballona, is the perfect person to provide an answer. Diego has both gone through this transition himself, and now is coaching engineers to become great engineering managers.

Diego writes a blog on topics including engineering leadership in articles like Managing engineering teams outside your technical expertise, Calibrations for software engineering interviews and Advice on doing well on system design interviews. You can also follow him on Twitter.

Over to Diego:

When I transitioned to my first formal management role, I remember feeling that I was doing well as an engineer with minimal effort. Work just flowed naturally. I gave folks code pointers sometimes without looking at the codebase. When posed with challenges, I knew how to act and get to the solution.

In this new role as a manager though, I barely knew where to start, most of the time.

In all candour, feeling lost is somewhat reflective of the truth. Those who transition from individual contributor (IC) to engineering manager (EM) probably relate to this. The journey from junior engineer to senior engineer feels like a continuum, where your perspective of the work changes with each stage of progression. However, the IC to EM transition means learning an entirely different job. The change starts long before you get the title and takes much longer to complete, afterward.

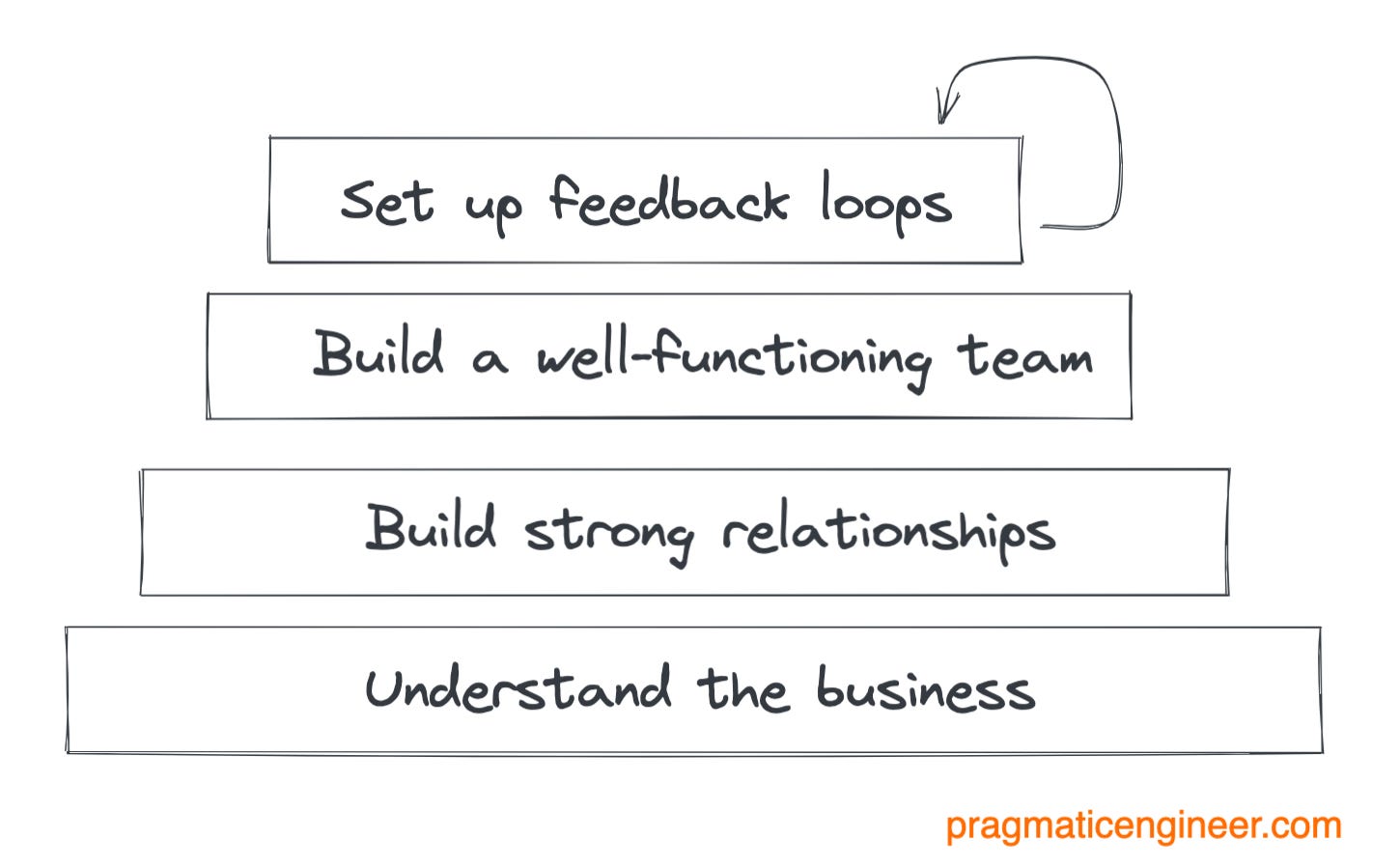

In this article we cover:

Transitioning from IC to EM. What the transition consists of, and how to be prepared for the opportunity when it arises.

Typical transition paths. The more common ways to transition into a manager position.

Your first year in your new role. A primer on the EM role, how to navigate the role change and where to focus your energy.

Building a well-functioning team. Three qualities that are components of well-functioning teams and how to achieve them.

Set up feedback loops. To get better, as a manager, you need to know what is not going well.

Growing as an engineering manager. How to keep growing and learning once you've established yourself in the EM role.

1. Transitioning from IC to EM

In most tech companies, the career progression path in engineering forks at around the senior level into two distinct paths. Once at the senior level, you choose if you'd like to progress in the individual contribution craft, as a staff+ engineer, or the engineering management track.

There are good reasons why this happens at around the senior level. Beyond the senior level, you need some degree of specialisation in order to perform the role. It becomes ineffective to keep shifting between solving complex organisational problems and driving deeply technical challenges toward clarity.

It's natural then that senior engineers might feel interested in trying engineering management to progress their careers. But what does it take to make this career transition a success?

The expectations of the role

Many people don't know what the day-to-day looks like for an EM. After all, what do managers do beyond 1:1s and hopping between meetings all day long?

Perhaps the best way to understand what being an EM means is by looking at your company's career ladder framework, which outlines levels and expectations for EMs. Most of the time, expectations boil down to four dimensions:

Technology Strategy: how this person enables the team to build great technology. How they ensure software being shipped is of high quality, that the team has sound engineering practices, and that there is an underlying tech strategy and vision articulating how the team's systems and architecture will evolve over time.

Business Impact: the impact of the software this team ships, relative to the size of the team. The primary measure is not productivity or throughput, but rather how this team enables the overarching business outcomes and how the EM plays a role in making them happen.

Process & Delivery: how this person organises their team. How well they work and collaborate with external stakeholders, ensure accountability is well defined, risks are flagged in proactive ways, and the team functions sustainably and autonomously.

People Management: how this person empowers the people they support. This is not just what their reports have to say, but how this EM promotes growth, matches people to their strengths and growth paths, hires for gaps in capability, and builds a diverse team that fosters a sense of inclusivity and belonging.

Understanding these expectations hints at what the model of the role is. Rather than just reading about it, a great person to talk about the expectations for EMs, is your manager. Besides knowing the expectations, they can help you understand these expectations from a familiar perspective.

Be prepared for the opportunity

Engineering management roles are rarer: you first need enough engineers in a team for a manager to exist. A significant component of being considered for the role once the opportunity arises is showcasing leadership traits as an engineer.

Know how to manage yourself. While this can sound obvious, it is not an easy task. It's not unusual even for senior leaders to mismanage themselves. Typical examples of mismanaging yourself include:

Seeking hard goals, forgetting to pace yourself and burning out as a result.

Drowning in tactics because of pressure and failing to think longer-term.

Focusing on speed of execution, mistaking motion for progress and noise for signal.

Learning how to manage yourself is a cornerstone of management and leadership.

Know how to manage up. The best reports I ever had made my job easy. Not because they didn't need my guidance and support, but because they held me accountable for what they needed from me.

Managing up is fundamentally doing a part of your boss's work, so it's an excellent way to show aptitude for the role. A good example of managing up is taking ownership of problems in the team and coming up with options and a recommendation, rather than just talking about it.

Naturally, when opportunities came, these were the people I thought of first.

Propose solutions to problems. When you're a manager, accountability becomes an even higher expectation. As a manager, your accountability spans beyond your direct team; it percolates the overarching organisational culture, hiring, fairness, diversity, belonging and inclusion. Leaving issues aside has a much larger blast radius, impacting other people. Holding yourself and others accountable for resolving problems is another key trait that makes you prepared for the opportunity.

When you spot something that feels wrong, flag it to the accountable party, and beyond that, make a recommendation for a path forward. You may not have the answers, but start the conversation.

Prioritise hard. In a high accountability environment, one common trap is trying to solve everything that feels wrong. The issue though is that the more responsibility you are trusted with, the harder it is to get to the bottom of your list of problems. It becomes essential for EMs to prioritize well to avoid hindering the team's ability to focus. These traits are also widely applicable for strong individual contributors; they know what matters most and so focus their energy on that.

Keep a running list of your priorities and every time something new comes in, add it to the list. This same list can also serve as a way to set expectations with your manager in case you are unsure, plus it gives visibility on what you are not doing – which can sometimes be as important as the things you are doing.

Most importantly, you should ask for what you want. Most of the time, doing so goes a long way.

2. Typical transition paths

While there are many paths to engineering management, some seem to be more common than others:

Tech lead to tech lead manager. You may be operating as a "tech lead" (TL) after you have performed the senior engineer role for some time and have a track record of supporting engineers less senior than you. "Tech lead" is a situational role and less frequently a title, and its responsibilities may overlap with EM responsibilities. This overlap makes TLs strong candidates for EM roles. Commonly, TLs will step into the EM role and still do some of their individual contribution work as a tech lead manager (TLM).

Move to a smaller company and become a first-time manager. Another common path into management is moving from a larger company as a senior engineer doing the aforementioned TL role, to join a smaller company as an EM. Sometimes this means leaving as a senior engineer, being hired as a staff engineer, and then moving to management.

Staff+ Engineer to EM: In many companies, the engineering career ladder framework has corresponding IC / EM levels, whereby you can do a sideways career move. In most cases, a staff engineer would move to an experienced EM role, right above the TLM / first-time manager level. For some, a more natural progression is to go through the staff engineer path first and then transition into management.

There are many other transition paths, but the underlying commonalities are that a prospective IC transitioning to the EM role needs to have had some experience of being a senior or staff engineer and has showcased strong leadership traits.

A last missing bit is the need for a new EM to step up. It can come through your manager quitting, a restructuring in the organisation, your team growing to a point where your manager has more reports than they can manage, and many other situations. As the stars align – or you align them yourself by convincing your manager you can manage a part of the team – you'll be on your way.

3. Your first year in the role

So you are given the opportunity to do the role in the interim. After a couple of months, your performance evaluation results come back, and you get the formal title. And alongside the title comes your share of questions.

How are you going to share this with your former peers? How will person X feel about you becoming their boss? Will people still trust you the way they did? Will your new role change the team? Will you even enjoy being a manager?

In your first year as an EM, some fundamentals can help you establish yourself.

Understand the business

In a company, nothing exists in isolation. Everything serves a broader context. As an engineering leader, to be successful, you and your team need to be aligned with the business. You will not be successful if you jump straight into the tech side without understanding the purpose of the team. A large part of an engineering manager's role is building bridges between the team and the broader context. Only with this context in place can you execute against the goals.

Build an opinion as the engineering leader for the team. To build a well-informed opinion, you need two inputs:

Local context: within your team and adjacent ones.

Global context: the company's objectives.

For local context, start building your opinion by making use of Boz's career cold start algorithm. Pick one person in the team and book a 30-minute conversation. During this conversation, ask them:

To tell you what they think you need to know

What the team's current challenges are

For a list of people they think you should talk to

Rinse and repeat until there are no new names.

By doing this, you'll hear stories repeated from different angles, conflicting opinions, and things that may feel confusing. As you go through the process, you’ll start coming up with your own beliefs. You will also begin building the relationships which will enable you to be successful in the role.

For global context, spend time reading and catching up on what's happening at the company. This is necessary to understand how the work you and your team does maps to the broader company mission. It also helps you spot opportunities to be impactful.

If you only focus on local context, you will create a myopic view of purpose. A few ideas for what you could do instead, are:

Block a few hours per week to meet people elsewhere in the organisation.

Attend all-hands meetings for your own team and sibling teams.

Subscribe to internal communications channels.

Have a "read later" list.

The more you understand the business, the better positioned you are to shape its direction. Ways you can shape direction include writing engineering strategy, partnering with product and stakeholders to develop a consolidated roadmap and defining longer-term Objectives and Key Results (OKRs).

Be ready to revisit and adapt your observations regularly. The context changes frequently in fast-moving companies, so you’ll need to keep up. Treat shaping direction as a curious observation, rather than fate or an irreversible prediction. The value of strategy, roadmaps or goals is giving folks around you a sneak peek into the future, as you and your team see it today. Turn these artifacts into an alignment force for your team, peers, manager, and stakeholders, but be open to change if that's the right thing to do.

Build strong relationships

Your success in a leadership role largely depends on your ability to build and nurture relationships. This part of the work has to do with how well you can work with others and support and be supported by them:

With your manager. In a healthy environment, your manager is the second most interested party in your success, after only yourself. Asking for help is fundamental to your success. As a new manager, you might assume that now you have to deal with everything yourself. Instead, learn how to use your manager and be okay with being supported by them.

With your peers. Make your manager's reports your "first team." Do this to avoid the feeling of loneliness that can come with a leadership role. Your manager's reports face similar challenges to yours. They are more likely to have a useful perspective on your challenges.

With your cross-functional peers. Engineering teams are usually part of a broader cross-functional team, with product, data, research, design, operations and other counterparts. As an engineering manager, these partners directly impact the outcomes of your work and your team's work. They are fundamental to your success and your team's success.

With your direct reports. Your team defines the largest portion of your success as a leader. A team is a group of individuals, and your success as a manager comes from building an effective, motivated, and impactful group of people. The way people will get the most from you is by you understanding them as human beings, well beyond their technical skills.

If you don't intentionally invest time in these relationships, they will become strictly transactional. Or worse, the lack of relationships may get in the way of getting work done.

4. Building a well-functioning team

Happy teams share characteristics which are not easy to create but are simple to understand. Here are three qualities that are components of well-functioning teams: