Paying down tech debt

A guide for reducing tech debt effectively, and how to develop a mindset that welcomes the short-term benefits of eliminating it. A guest post by principal engineer Lou Franco

Before we start: since publishing this article, Lou has finished the book Swimming in Tech Debt. You can get it here for $0.99 during a presale period. The below article was originally a paid one, but since 5 Sep 2025 is a free article, to celebrate Lou publishing his book.

Q: “I’d like to make a better case for paying down tech debt on my team. What are some proven approaches for this?”

The tension in finding the right balance between shipping features and paying down accumulated tech debt is as old as software engineering. There’s no one answer on how best to reduce tech debt, and opinion is divided about whether zero tech debt is even a good thing to aim for. But approaches for doing it exist which work well for most teams.

To tackle this eternal topic, I turned to industry veteran Lou Franco, who’s been in the software business for over 30 years as an engineer, EM, and executive. He’s also worked at four startups and the companies that later acquired them; most recently Atlassian as a Principal Engineer on the Trello iOS app.

He’s currently an operating partner at private equity firm SilverTree Equity, and technical co-founder at a new startup. Lou says he isn’t delighted about the volume of tech debt accumulated during his career, but is satisfied with how much of it he’s managed to pay down.

In this guest post, Lou shares insights about how to approach tech debt. Later this year, he’s publishing a book on the subject. For updates on this upcoming release, subscribe here.

In this article, we cover:

Pay down tech debt to go faster, now. It’s common for less experienced engineering leaders to assume that focusing on features and ignoring tech debt is how to move faster. Lou used to agree, but not any more.

Use tech debt to boost productivity. Three examples of when tackling tech debt empowered engineering teams to move faster, right away.

Link tech debt and value delivery. When tech debt is tackled sensibly, it delivers business value. At Trello and Atalasoft, this was how Lou got engineers and management to appreciate the task.

Make tech debt’s effects visible. Dashboards are an effective way to visualize the impact of tech debt. A few examples.

Factor in time saved when thinking about productivity. Reducing tech debt typically improves coding, reviewing, and deployment for everyone.

Use tech debt payments to get into the flow. In a counter-intuitive observation: by making small, non-functional improvements, you gain more confidence in a new codebase, and can start to move faster.

Big rewrites need heavyweight support. Without the backing of management, a large-scale rewrite is likely to fail.

With that, it’s over to Lou:

1. Pay down tech debt to go faster immediately

What is tech debt?

I define tech debt as any problem in the codebase that affects programmers by making it harder to make necessary changes. As a programmer, I wanted to fix such issues because they slowed me down. But as a manager, I had to ensure the team delivered value to stakeholders. I’ve gone back and forth between these roles during my career, and made mistakes in both directions – but I also learned a lot about getting the balance right.

Reducing tech debt pays off immediately in faster builds

In 2010, I was head of development at Atalasoft, a company in the .NET developer tools space. I was obsessed with shipping, and spent all my time worrying about delivering the features in our roadmap. Over time, we improved at this, which showed up in our revenue growth and eventually led to an acquisition.

We were in a competitive market with more opportunities than we could handle. We had fewer than ten developers, but we were bootstrapped, so had to stay profitable and couldn’t just hire ahead of revenue.

The stakes got even higher after we were acquired. We had two years to deliver on an ambitious roadmap, for which there was an earnout bonus contingent upon delivery. If we didn’t deliver, we’d likely be classified as a failed acquisition. Our new owners had just had one such failure, which led to downsizing and an office closure.

My mindset was that any time spent on technical debt meant we’d fail to deliver on the roadmap. We couldn’t risk the deadline by wasting time cleaning up old messes, and had to choose between tech debt and roadmap delivery. In hindsight, I see this was wrong. I learned that the mindset of ignoring tech debt hurt my team.

Following an exit interview in which a departing engineer mentioned tech debt had contributed to their decision to leave, I started asking people during 1:1s how they felt about it. Their responses showed their frustration with me.

By then, I had been a developer for over fifteen years, and had worked in codebases with a lot of debt, so I knew what it was like. But by now, I was a manager who sometimes contributed code, but had forgotten what it was like to be thwarted by the codebase every day. To my team, I was part of the problem. They had been trying to tell me this, but I didn’t get it. Their departing colleague with nothing to lose in their exit interview finally got through to me and helped me understand the depth of the issue, and that it was slowing everyone down.

I learned an important lesson: the cost of tech debt is borne daily by your team, and you risk damaging motivation and raising attrition by ignoring it. Even if you have every reason to move forward without addressing tech debt, being an empathic manager requires you at least do something. Doing nothing – like I did – is not a good option.

So we started making changes. The biggest problems were with our build system and installer because they affected every developer and every product. It was a tangled bag of legacy code that needed constant maintenance, but it wasn’t very big, and I approved a plan to rewrite it with modern tools. It was a small experiment but paid off right away in quicker CI builds and an easier-to-modify codebase. Most importantly, I saw it didn’t derail our roadmap, so we took on other small initiatives.

This taught me another lesson about addressing technical debt. I had thought of it as something that might pay off in the long run. Might. This belief made it hard to justify doing it when I had to deliver on short-term goals. But instead, something else happened:

We paid off tech debt and increased productivity instantly! We had a build with faster feedback loops, less cognitive load, and which didn’t make developers frustrated when they had to add to it, which happened regularly. Updates were made with less code and without breaking things. It was an example of tech debt reduction paying off in increased developer productivity, right away.

Learning the cost of too much rewriting at Trello

I got my next lesson at Trello where I worked on the iOS app. The codebase was three years old when I joined in 2014. It had understandable tech debt because they needed to move fast, after going from 0 to 6 million sign ups. The devs working on it were founding engineers, working as described by The Pragmatic Engineer in Thriving as a Founding Engineer, and seeking product-market fit. Our biggest tech debt issue were some frameworks that made it fast to build a simple app, but held us back as the app got more complex.

Our own choices were influenced by the speed of Apple’s updates to iOS. The iOS 7 update completely changed the iOS design language and its network APIs. Later, iOS 8 introduced presentation controllers that gave developers much control over the animation when new views are shown. Unfortunately, the iOS 8 change broke our navigation code and caused crashes. These added up and started to make our code seem antiquated.

Our code got even more complex when Apple decided to feature Trello on physical iPhones at Apple Stores. To be in stores, we needed a build that worked without an account or a network, so a mock backend was embedded in it for demo purposes. We didn’t want to maintain a separate codebase, so had a lot of random bits of demo-mode logic that stayed for years.

At Trello, I was coding every day and all this was in my face. Luckily, we were a small team of three developers, so my direct manager was also coding every day and was empathetic to the problems.

We did rewrites as we went, but sometimes went too far. To deal with the presentation controller problem of iOS 8, we developed a new paradigm for screen navigation inside the app, and rewrote all navigation to use it. This approach was the exact opposite of what I did at Atalasoft, where I’d ignored all tech debt.

Unfortunately, the approach of rewriting early turned out to be overkill. In hindsight, we could have just corrected the places that had crashed, and then lived with the code we had. Instead, we spent a few months designing and implementing a new, non-standard way of writing navigation code, but forgot a vital lesson that one of our founders, Joel Spolsky, identified in 2000 in Things You Should Never Do:

“We’re programmers. Programmers are, in their hearts, architects, and the first thing they want to do when they get to a site is to bulldoze the place flat and build something grand. We’re not excited by incremental renovation: tinkering, improving, planting flower beds.

There’s a subtle reason that programmers always want to throw away the code and start over. The reason is that they think the old code is a mess. And here is the interesting observation: they are probably wrong. The reason that they think the old code is a mess is because of a cardinal, fundamental law of programming:

It’s harder to read code than to write it.”

On the Trello engineering team, we were all very familiar with this article and quoted it to each other often, but it still sometimes bit us. The urge to rewrite a system instead of fixing it is strong, and we couldn’t resist! We should have addressed the few complex navigation cases that crashed our code without the full rewrite.

Size tech debt payment to be proportional to value. This is the biggest lesson I learned on this project.

I’ve seen both extremes of dealing with tech debt:

As a manager, I was overly resistant to devoting time to dealing with technical debt

As an engineer, I was exposed to its problems every day and didn’t resist the urge to pay it off enough

These two extremes form the fundamental tension of dealing with tech debt. As usual, there needs to be a balance, but finding it is not so easy.

The heuristic I use to pay tech debt these days is this: by reducing a specific tech debt, can I increase developer productivity and deliver business value right now?

If I can’t, then I don’t pay it down.

When the debt is so big that it couldn’t possibly deliver value now, or the value is invisible so nobody sees it, I do something else. Let me break down my heuristic…

2. Use tech debt to increase productivity

I try to pay down a little bit of tech debt regularly by making small cleanup commits as I go. I started doing this more intentionally after reading Kent Beck’s book, Extreme Programming Explained, in 1999, which introduced me to automated unit tests and continuous integration. Then, when I read Martin Fowler’s Refactoring, I started to see how to improve a codebase over time with very small, behavior-preserving changes checked by unit tests. In both books, and in others like Working Effectively with Legacy Code by Michael Feathers, and Kent Beck’s recent, Tidy First?, the authors stress that technical debt is inevitable, and that the main way to curtail it is to be constantly fixing it with small improvements enabled by unit tests and mechanical refactoring. I agree.

Unit tests, refactoring, and continuous integration are ubiquitous in the kinds of software I write, which are B2B SaaS productivity applications. Even making small improvements on an ongoing basis is common among my coworkers. It doesn’t take long, and there are usually quick wins to be had, like making the code more readable, or using a unit test to show how the code is supposed to work. Even in frontend code, Trello iOS adopted Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) so we could test view-logic. We got the immediate productivity benefit of being able to run view code repeatedly without needing to manipulate a running app through several screens to check that our changes worked.

The issue is when the debt is large, which is where I struggled. My problem at Atalasoft was not with small improvements; it was with the bigger ones where I’d have to trade off current benefits like delivering features for the roadmap, for uncertain future benefits.

But I realized something.

You can get productivity benefits immediately, even with larger initiatives. If you do it right, you will deliver feature work faster and with higher quality. In fact, I view tech debt proposals that don’t deliver instant developer productivity gains as suspect.

Rewriting the build and installer at Atalasoft brought an immediate productivity boost. We had a backlog of problems and new additions, but the rewrite took one developer around a month, and when it was done many of the problems just went away because the new system was based on a framework wherein many problems could not occur, meaning we could close a bunch of reported bugs. The new system was unit testable, so we didn’t need to build and install the entire system during development to test our new changes while we were writing it. We also got more benefits later, but the instant benefits justified it.

At Trello, adding unit tests to a codebase helped me finish a project faster. When I joined in 2014, we were just about to start our internationalization (i18n) project, which I took on for the iOS app. One part was to write support for i18n-safe string interpolation (inserting variables or expressions into a string,) and pluralization (adjusting words to plural forms based on the number they refer to, to make the phrases grammatically correct) – which was only partially supported in iOS at the time. It’s standard string manipulation at its core, but in 2014 our iOS app didn’t have unit tests.

Without unit tests, if I had wanted to run the code, I’d need to run the app and then tap-tap-tap until I got to a specific string. I would have to do this for each kind of string I generated. But with unit-tests, I could just list all the examples with their expected results, and run tests in less than a second. So, I proposed to the team to add unit tests to our build and CI.

No one was against unit tests, but it hadn’t been a priority. Most of the code was UI or network code, for which unit tests are harder to write. But the code I was writing was highly testable, and in fact, it’s harder to write without tests. So, I added the unit test project to our workspace and wrote the string code. With the unit test project there, the other developers added tests to their work. I was there for six more years, and saw the benefits of the tests over time, especially in complex code like our sync engine. But that’s not why I did it: I added the unit tests to go faster immediately.

Also at Trello, creating an abstraction layer for the design system made us more productive. Eventually, we created a design system with a reduced set of fonts, colors, and other design attributes and specific rules for using them. Before, it was common to see hardcoded values in view controllers throughout the app, as each screen implemented the designer’s specification for that screen, which wasn’t always consistent. We could have just updated those lines to the new approved values, but it was the perfect time to make an abstraction for the design system itself. Doing this made it faster to write code that matched a design, and when a default in the design system changed, it would be reflected everywhere.

These three examples also adhere to another heuristic I use for finding the right balance with tech debt: coupling it with delivery of value.

3. Couple tech debt fixes with value delivery

It’s hard to talk about technical debt outside of engineering because the problems we tackle exist inside the codebase, which is invisible to people not in engineering, But for us, it's the water we swim in.

When we need to make changes in a codebase with a lot of debt, it’s like swimming upstream. We eventually get there, but others just see the result; they don’t know about the struggle. If we get bogged down, it just looks like we're slow swimmers.

Engineering leaders tend to talk about reducing debt as an end in itself – which is a mistake! When we report a tech debt fix as a deliverable, colleagues not in engineering can’t do anything with this information. If a product marketer comes to your demo to take notes for a launch, you don’t want them to leave with a blank sheet of paper because nothing in the product changed. To mitigate this, pay down debt that makes it faster to implement high priority product changes, and then highlight the benefits of those changes, not the debt.

An analogy helped me understand this. In the early days of surgery, doctors didn’t usually wash their hands before operations, which made infections and deaths more likely. Today, it would be unheard of for a doctor to not wash their hands. But after surgery, doctors don’t talk about handwashing, they talk about the success of the operation.

To take this analogy further, the medical community discusses process improvements a lot. Before it became common, there was debate about the effectiveness of handwashing. Proponents had to evangelize for it and persuade colleagues. We should do the same in engineering, so celebrate your tech debt payments all you want! Share stories with team mates to build a culture that values them. But like patients, who only care about whether the surgery succeeds, our stakeholders and customers only care that the software is better in an obvious way.

All three examples from the previous section delivered business value and boosted developer productivity:

At Atalasoft, the new build and installer were much higher quality, and many bugs just vanished.

At Trello, the unit tests I added made it possible to implement i18n string interpolation and pluralization in a way that was easy for translators to understand, and that’s what I demoed at our sprint review.

Also at Trello, when we cleaned up all the hardcoded UI values and implemented the design system, we showed how screens matched it.

QA understood us, designers understood us, PMs understood us, and translators understood us. When we did it right, marketing and sales could turn sprint demos into webinars and sales pitches. Executives could see alignment with OKRs.

We should not hide tech debt, but make it as obvious as possible to engineering and engineering management. The bigger the debt, the more we need to involve them. But to others, we’re emphasizing the value we delivered because it can be seen, whereas debt cannot.

There are times when you know debt is bad, but paying it won’t deliver on the roadmap. Or maybe you’d like to talk about productivity improvements because of technical debt payments. To address that, I recommend trying to make the effect of the debt more visible.

4. Make tech debt’s effects visible

In 2019, I was at Atlassian which had acquired Trello, when the CTO declared the entire engineering organization would stop all feature development and address company-wide reliability issues for a few weeks. Our CTO later said:

“We didn't allocate enough time on our roadmaps to address technical debt which had accumulated [...] This included the need for reducing technical complexity, improving observability, and addressing root causes when problems occurred.”

All feature development at the company was suspended for projects that improved reliability. I decided to concentrate on the Trello iOS app’s sync system, which lets you make changes offline that would be sent to servers later. We didn’t expect the sync system to be 100% reliable, but had support cases that indicated it was below standard. Since those cases were hard to reproduce, and we weren’t sure how widespread the issue was because we didn’t know our overall error rate, they weren’t given high priority.

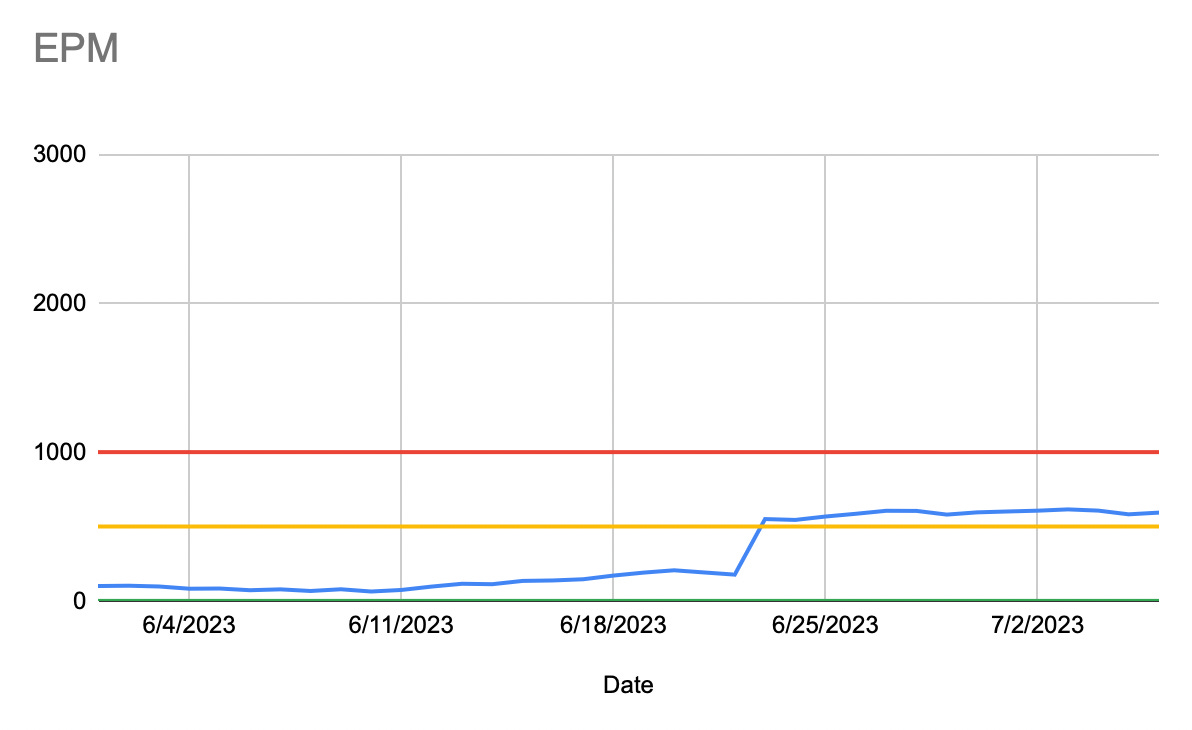

I would have needed more than a couple of weeks to diagnose and address the sync reliability issues, so I worked on the logging and dashboards to at least get a better measurement of reliability. When we could see our error rate, which engineering and product management all agreed was unacceptable, we picked an acceptable error rate and defined an even higher standard of “excellence.” We treated an unacceptable error rate like an incident and wrote an incident response guide for it following Atlassian’s playbook. Over time, the most common problems were fixed, and we reduced the error rate by 75%.

Before the dashboard, we couldn’t justify working on the sync system. But after we built it, we could see exactly how many users had each kind of sync problem, and knew the value of fixing it. More critically, we knew a fix worked after it was deployed.

To get stakeholders to notice tech debt, I made it more visible with an easy-to-understand dashboard. Most teams have some kind of observability requirement, but they’re usually geared towards detecting anomalies that are addressed immediately with small changes. The difference was that I knew a large subsystem of our code had a lot of debt which was causing problems, but I didn’t have proof. I directed observability at debt-laden code to show the problems were big enough to justify more than spot fixes.

Here’s a simplified version of the dashboard. In it, EPM means “Errors per Million.” We defined “excellence” as an EPM below the yellow line (500 EPM) and “acceptable” as between the yellow and red lines (between 500-1000 EPM). Above the red line was “unacceptable”. We used EPM because it’s easier to see the difference than with equivalent success rates. We wanted to go from 99.8% success to above 99.95%. In EPM, it’s 2,000 vs. 500 (4 times fewer errors).

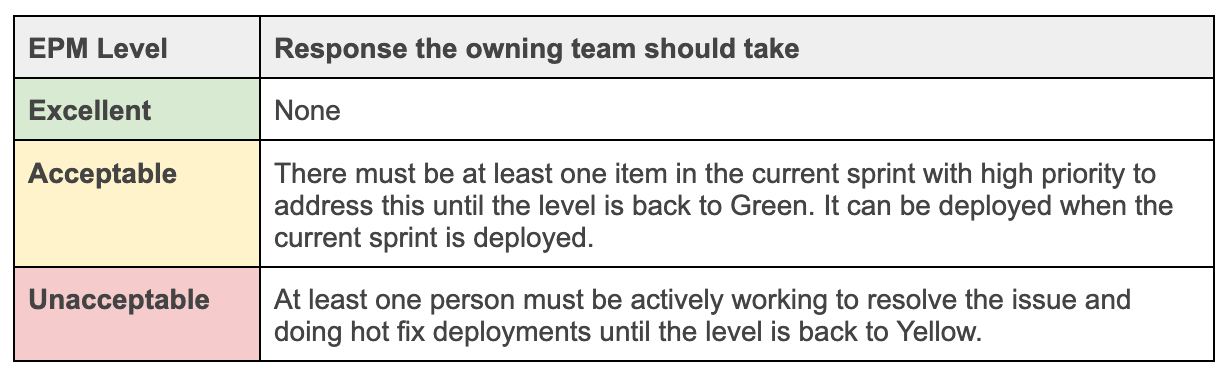

We also defined the response for each level:

These actions were negotiated with management and product managers, so we could just go ahead and fix things, instead of items getting lost in the backlog.

Aim to showcase the effect on customers, or at the very least, quantify the effect on developer productivity. Of course, to quantify developer productivity, you must be measuring it in some way. In my current advisory practice, I see acceptance of DORA, SPACE, and DevX productivity metrics, which I recommend looking at for ideas. In my experience, the kind of metric that works best is one based on reducing feedback loops, like CI build time, or code review time because they are easier to quantify. The Pragmatic Engineer previously covered approaches to measure developer productivity, and other deep dives on developer productivity.

Reducing feedback loops

Feedback loops manifest in a lot of ways. It could be the time it takes to build and test a system locally, how long it takes to get a PR reviewed, how long it takes for a CI run to finish, or how long it takes to get a design question answered. Whenever I had to wait, my biggest frustration was that it increased the difference between estimated work time and calendar time, which made my estimates wrong.

For example, at Trello, our app build times were between five and ten minutes. We complained that our laptops were too puny to build Trello, and got Mac Minis with a lot more RAM. This helped, but not enough.

Once we managed to visualize how unacceptably long builds took, it helped make the case to optimize it. One colleague wrote a small script that published our local and CI build times to the analytics database. Then, he built a dashboard to show how much time we were collectively waiting each day for builds. The results were unsurprising to us, but now we had something we could show.

It could be argued that this was affecting every single project, so it was easy for our manager to prioritize reducing build times. It turned out a big part of the problem was the intersection of Swift and Objective-C code, which gave us more reason to convert more code to Swift, paying off some debt, but directed at reducing build time and speeding up value delivery across the team. The effect of the conversion was visible on the dashboard and could be understood by everyone as a good thing.

Code coverage and code complexity

Another way to make debt more visible is by analyzing the code itself. I use a combination of coverage and complexity.

Code coverage is something we can gather during testing. It shows the percentage of lines that are covered, and in the case that a line is a conditional, it reports how we cover its various permutations.

Code complexity has many formal definitions, but for our purposes, we can estimate it as the number of branches in a function. You should count conditionals and each case in a switch, but also count a loop as a branch. If you use a boolean expression, you should count each boolean operator as a branch. You don't need a perfect count; we’re just trying to categorize it as simple or complex. Once over the threshold, you can stop.

I look for the combination of low coverage with high complexity. To make both of these metrics more evident, I installed the Coverage Gutters and CodeMetrics extensions in VSCode.

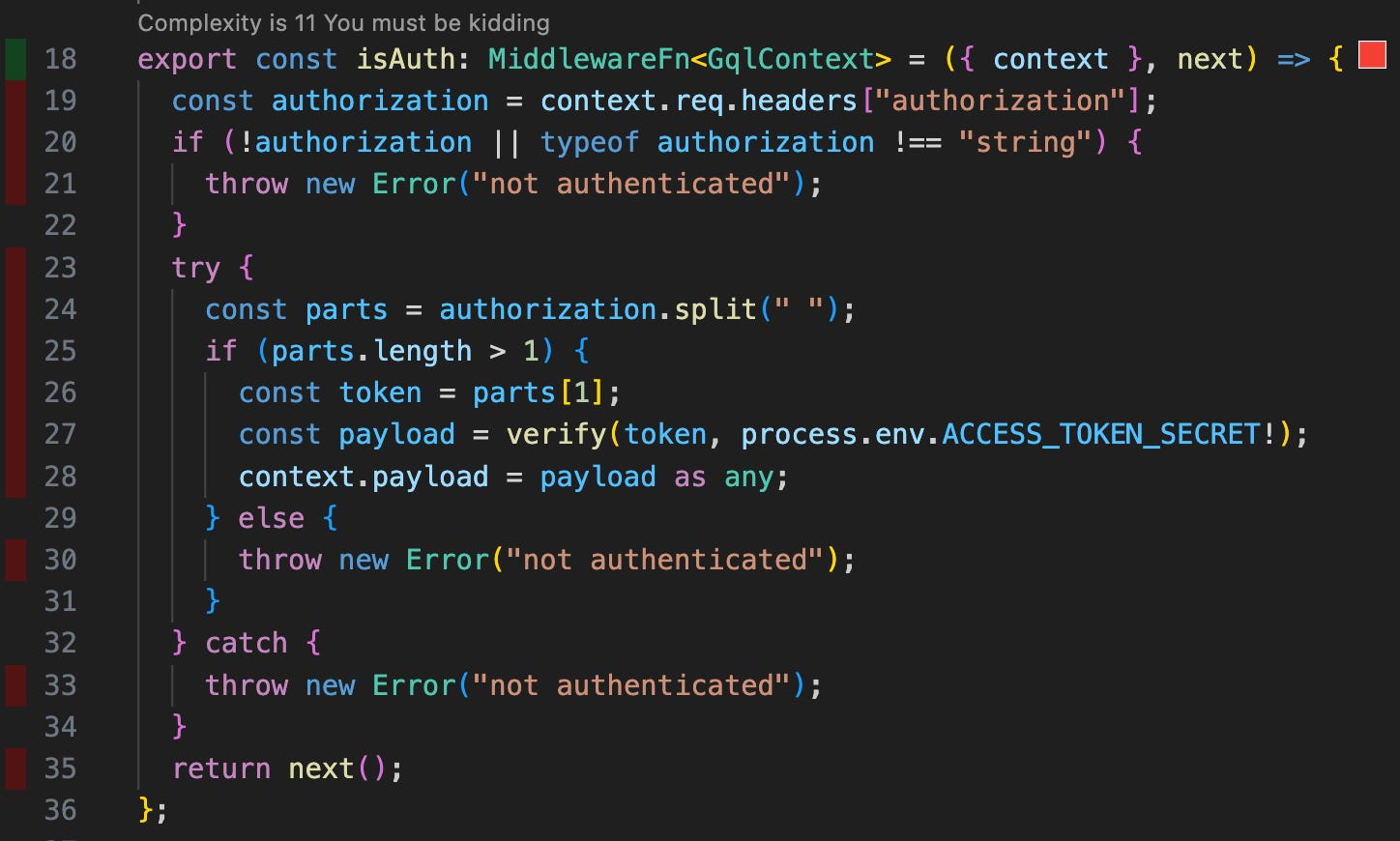

With those two extensions in place, whenever I am in a function that’s risky to change because it’s complex and under-tested, VSCode shows red indicators on the far left and top right, like this:

The faint, vertical red bars on the far left of the line numbers show that a function isn’t covered in testing. The red square at the end of line 18 shows that the function has high complexity, and there’s also a warning above the function.

This function is risky to change, but if needed, the first goal is to make one red indicator turn green. To do that, I can add tests to get coverage, or refactor to reduce complexity. If it’s easy, I’ll do both. In this case, it’s easier to break it down than test it.

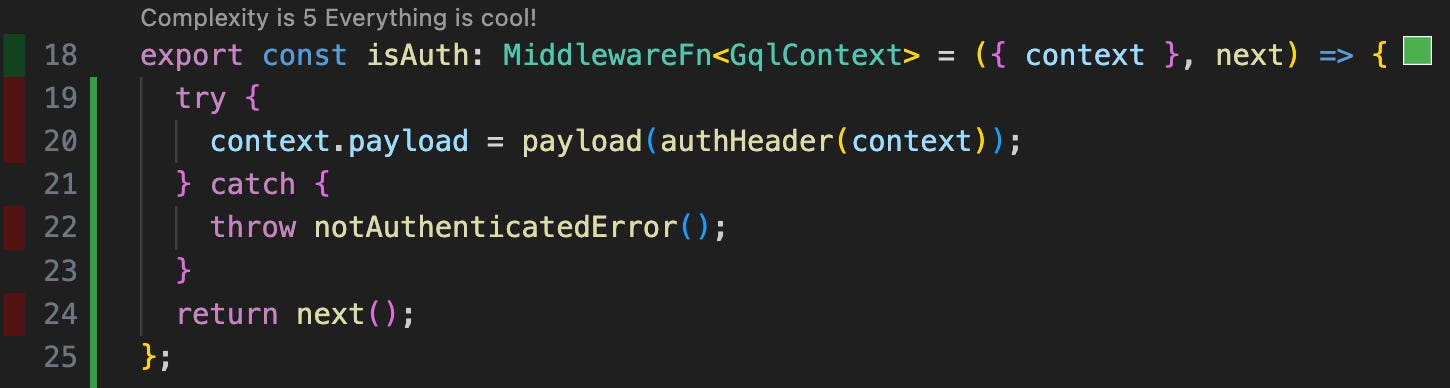

I do this in a few steps, ending up with this function:

This change only took a few minutes. The new functions (payload(), authHeader(), and notAuthenticatedError()) are trivial to test, so I did that too. Now I have four simple functions mostly covered by tests.

Doing this encourages me to make small fixes as I go, but data could also be collected about the entire codebase to show risky areas to change. I recommend using this information in estimates, to show how tech debt will affect a project. When I triage issues assigned to junior engineers, I quickly check the area that’s likely to change; if it’s under-tested and complex, I point that out and ask them to address it first.

To learn more about this metric, see this article on the Google Testing Blog.

5. Factor in time saved when thinking about productivity

My bias is to seek developer productivity gains almost immediately by paying technical debt. I hope there are long term gains too, but I found these often overstated. It’s related to the St. Petersburg paradox: we can always make an argument to invest in something if we add up future gains over an infinite future, no matter how improbable or small those gains might be.

When estimating the short-term impact of reducing tech debt, I include immediate benefits:

Code is easier to change without making mistakes

QA finds fewer regressions

Pull requests are faster to review because the code is easier to read

Build and deployment times are reduced

Here are examples of small changes that make outsized differences in several parts of the software development life cycle:

Adding a unit test. Makes it less likely QA will find a bug, or that new code will add a regression. I have also found that adding unit tests to code makes reviewing PRs much faster. This isn’t just because it’s more likely that the code is right, but also because it’s easier to know it’s right. There are lots of reasons tested code might create productivity gains in the future, but a faster code review pays off now.

Adding comments for ‘old’ code. If it takes time to figure out what code to change, it’s going to take time for a reviewer, too. So, I represent my learning in new comments around the code I am changing to speed up the code review. I also get the benefit that a reviewer may catch a mistake in my assumptions that wasn’t obvious in the code change.

Stacked diffs

No matter how short the review cycle is, it’s likely to still take a few hours. When I’m in the zone and don’t want to stop coding, I start working on the next PR. At Trello, I sometimes used techniques described in Stacked Diffs.

Stacking refers to breaking down a pull request (PR) for a feature into several, smaller PRs which all depend on each other – hence “stacked”. It might sound counterintuitive, but this workflow is incredibly efficient by making it easier to review and modify PRs.

We were working with BitBucket, which didn’t have direct support for stacked diffs at the time, so my biggest issue was dealing with problems in the first PR that rippled to others.

Our team valued small PRs, so I didn’t want to just combine them. But it was much better if the PRs in a stack weren’t overly dependent on previous ones. So, I often followed up a PR with new ones that paid down tech debt in the next area to be changed. When the first PR was approved, I moved on to the next change while the tech debt PR was under approval.

Doing this let me stay in a coding flow without context switching. Along with shorter feedback loops, the DevX model identifies increased flow and lower cognitive load as drivers of developer productivity. These are areas I seek short-term productivity gains from by paying debt. The Pragmatic Engineer did a deep dive on stacked diffs.

6. Use tech debt payments to get into the flow and stay in it

A good reason to add new comments to old code before you change it is to speed up a code review. Adding comments is also a good way to reduce cognitive load. When it takes me time to learn what code does, writing something down helps me remember what I figured out. Clarifying the code is even better.

Reducing tech debt as I go also helps me get into ‘the flow.’ We all know what it feels like to stare at code and wonder what it does, scrolling up, scrolling down, and then command-tabbing over to Slack to procrastinate. By making small changes as I learn the code, I get more confidence, and soon I find myself going from adding tests and comments to making more substantive changes. The tech-debt payments weren’t for some future benefit. They are helping me right now.

Once I have gotten into flow, staying in flow is so important that whenever I feel resistance to whatever change I’m making, I make a small code change to keep me from dropping out of it, applying the same techniques that I used to get into it.

Reducing tech debt as you go is also a great way to learn a new codebase. I learned this at my first job out of college, which was for a company that made DOS software to price foreign exchange options. When I started at the company, I didn’t know what a lot of the code was even supposed to do.

Every program has non-domain specific code. In the early 90’s, DOS programs like the ones my company made had its own Text UI screen rendering system. This rendering system was easy for me to understand, even on day one. Our rendering system was very memory inefficient, but that could be fixed. I spent my first couple of weeks rewriting each “window” of the application to make it more memory efficient. By doing so, I got to see every screen of the system. This project helped onboard me to the software, its structure, its build, and our issue tracking and version control workflows. I incidentally paid down some debt, but also learned how our software stack worked, while doing so!

I did this again when I started at Trello. My first project was supporting i18n (internationalization) in the app. The first step of that was getting each string in the code into a strings file that could be sent to translators. My goal was to fix the debt of hardcoded strings, but I learned a lot about the codebase and our process as I did it.

This has even worked unintentionally. When I was hired to work on a large-scale rewrite, I ended up being an expert on the legacy code as well because I had to read it every day to reimplement its features.

7. Big rewrites need heavyweight support

I avoid large scale rewrites, as I’ve seen them fail or drag on much more often than they succeeded. My biggest mistake personally was trying to rewrite a C/C++ system as memory safe C# code, which seemed like a good idea, but didn’t have the backing needed. It was eventually shelved. Sometimes it’s impossible to do this work in a way that delivers value until it’s done, so lots of commitment is required.

But I was also part of a two-year long rewrite that worked, and learned some things that I recommend to clients when they want to take one on.

In 2004, I was hired by ISO-NE, a non-profit that manages the electric grid in New England. There are ISOs all around the country established by the local energy companies to provide services to themselves – an important one is managing the electricity market, which trades 24x7 and determines the prices for generation. If it isn’t working, then there might be problems delivering electricity.

At ISO-NE, the electricity price publishing system was a pile of Bash, Perl, PHP, and C. These scripts mixed database access, HTML generation, and logic in unexpected ways. Sometimes a script would generate another script. You’d fix a bug in a generated script, and it would get overwritten. It was a mess!

I was hired to rewrite it as a clean Java-based system, and brought in for my experience with the legacy languages and J2EE. They doubled the team size from two to four to include a developer with a lot of Java Server Pages experience, and then later to eight members with contractors who only worked on the new system. They hired a manager who had done this kind of project before, and set a target date of nearly two years. The first lesson I learned about big rewrites was not to underestimate them.

The size of the project was well-understood and planned. Frankly, having two years for a rewrite with such a large team seemed wrong to me. In the end, we needed that time. We got these resources because the current situation was untenable: the code was fragile and mission critical, and our stakeholders ranked reliability as the #1 priority.

We ensured the legacy system was improved during the rewrite. I was hired to work full-time on the new code, but we realized the best thing for me to do was spending some time maintaining legacy code. Contractors were recruited for their expertise in the new system, so couldn’t work on the legacy one. Because I was in both codebases, whenever I did something new with the legacy code I added it to the new code, or updated the spec. By the end of the project, all the non-contract engineers were working on both codebases in the same ratio as each other. The systems were built in parallel and both kept running during an overlap period, much like Gergely describes in Migrations Done Well.

We coupled the rewrite with a user-facing improvement project. We coupled the rewrite – which was invisible to users – with a move to a customer relationship management system (CRM). We branded both projects as “Warp” (Web Application Redesign Project). Our content management was implemented with similar home-spun scripts maintained by the same developers. We moved to an enterprise CRM system and created a fresh design.

Throughout the project, we mostly talked about things users could see, like the new design, the easier way to update content, the content workflow, etc. After the system had been up for a while, we could talk about the reduction of incidents and other improved reliability metrics because these were heavily monitored at ISO-NE, and showed significant improvement.

If the state of your system is untenable and a rewrite in small chunks over time isn’t possible, then ensure everyone in the company, all the way up to the executive management team, agrees and understands what needs to be done. Don’t underestimate what it will take.

This is the most important lesson, and it’s what I saw work at Atlassian fifteen years later in a multi-year rewrite that transformed the business from a mostly on-premises company to a cloud based one.

When doing a large-scale rewrite, the work will require a temporary increase in the number of developers, which can be done with contractors or temporary reassignment if your company has the resources. Recruit expertise in a new technology and front-line managers that have done it before.

It also helped us to couple the project with one that was more visible to stakeholders. This was fine because it was maintained by the same team and had similar issues. If you can find a way to do it, you’ll have something to show when you’re done, and can follow up with quality metrics after measuring them.

Takeaways

Gergely, again.

Thanks to Lou for sharing some hard-earned experience and advice for taming tech debt. As mentioned, Lou is working on a book dedicated to this topic; sign up to get emails from him with more thoughts about managing tech debt, and to be notified when the book is ready. If you have suggestions of topics for Lou to cover in the upcoming book, please connect with him on Linked In, or via his website.

If you’re interested in diving into some reading, Lou recommends:

Tidy First? By Kent Beck (we previously covered three chapters from this book)

Refactoring by Martin Fowler

Working Effectively with Legacy Code by Michael Feathers

My biggest takeaways from Lou’s deep dive on tech debt removal are these:

It’s easier to tie tech debt to business value than you think! Any sensible company — even tech companies! – will resist spending time on things that make no difference to business results. So make it clear that addressing developer pain points will make a difference by improving reliability, development speed, and other areas. Use visuals and dashboards which make your point.

Couple tech debt-removal projects with user-facing work. It’s often easier to build a complex feature if you make large changes to the underlying architecture. So do this when possible!

If there is no visible impact: is it really worth spending time on it? It’s easier to justify the work for tech debt removal when you can showcase the positive impact of the work. Challenge yourself: can you create a dashboard or some other visualization to showcase the expected/actual impact of reducing this debt? Remember: visualizing time saved for developers should be possible with some time on monetary value. If you still struggle to do this: ask yourself why this is, and if the work is really as important as you think it is.

Beware rewrites without sufficient support. Doing large rewrites – in which a lot of engineers help out, or which take a long time – is only sensible if there is support from above. There are plenty of cases when such rewrites are necessary: if so, convince the leadership! Also, link a rewrite with shipping new, better, user-facing functionality, where possible.

I hope you enjoyed this practical take on how to pay down tech debt. As Lou puts it so well: dealing with debt involves a constant tension between delivering business value and maintainability. It’s down to us engineers to strike the right balance as best we can.

> We’re not excited by incremental renovation: tinkering, improving, planting flower beds.

it's a small thing to focus on but I really dislike this quote and this view. it is not true in my experience that we are all, or even mostly, like this. it is my experience that people who like building something new are given greater recognition and reward for their efforts. the industry is self selecting for this trait, and many others get pushed sideways into other roles including tpm, manager, and sre.

a common way this manifests is a project with two implementation proposals - write it in place with fixes to the whole flow so it's all cohesive, or write it in brand new code in a brand new microservice and database table with an if statement. 9/10 times people in power select the latter - because the estimates are a few weeks shorter, and everyone involved will get a big boost to their next performance review. but within a year those 3 saved weeks are long lost - emergency scaling, edge cases going to the wrong flow, backfills, reimplementing guards that exist in the old flow, implementing the next feature twice, and an increased operational load.

a year later, everyone will agree it was a mistake, but yet still dont listen the next time someone speaks up and says "let's fix what we have to handle it."

if we want people to take a step back and think critically about that big rewrite, you should make sure the people who do it naturally are in the room, sufficiently promoted, and their opinions valued.

Very cool article! Totally matches my experience as well.