The Software Engineer’s Guidebook: a recap

Reflections on publishing The Software Engineer’s Guidebook two years ago, which has sold around 40,000 copies. Also: an unexpected trip to Mongolia to visit the startup which translated it

Before we start: I’ll be in San Francisco on 11 Feb, 2026. I’m working on something special for engineers and engineering leaders: The Pragmatic Summit. I can’t wait to share more. 11 February – save the date! And see more details here.

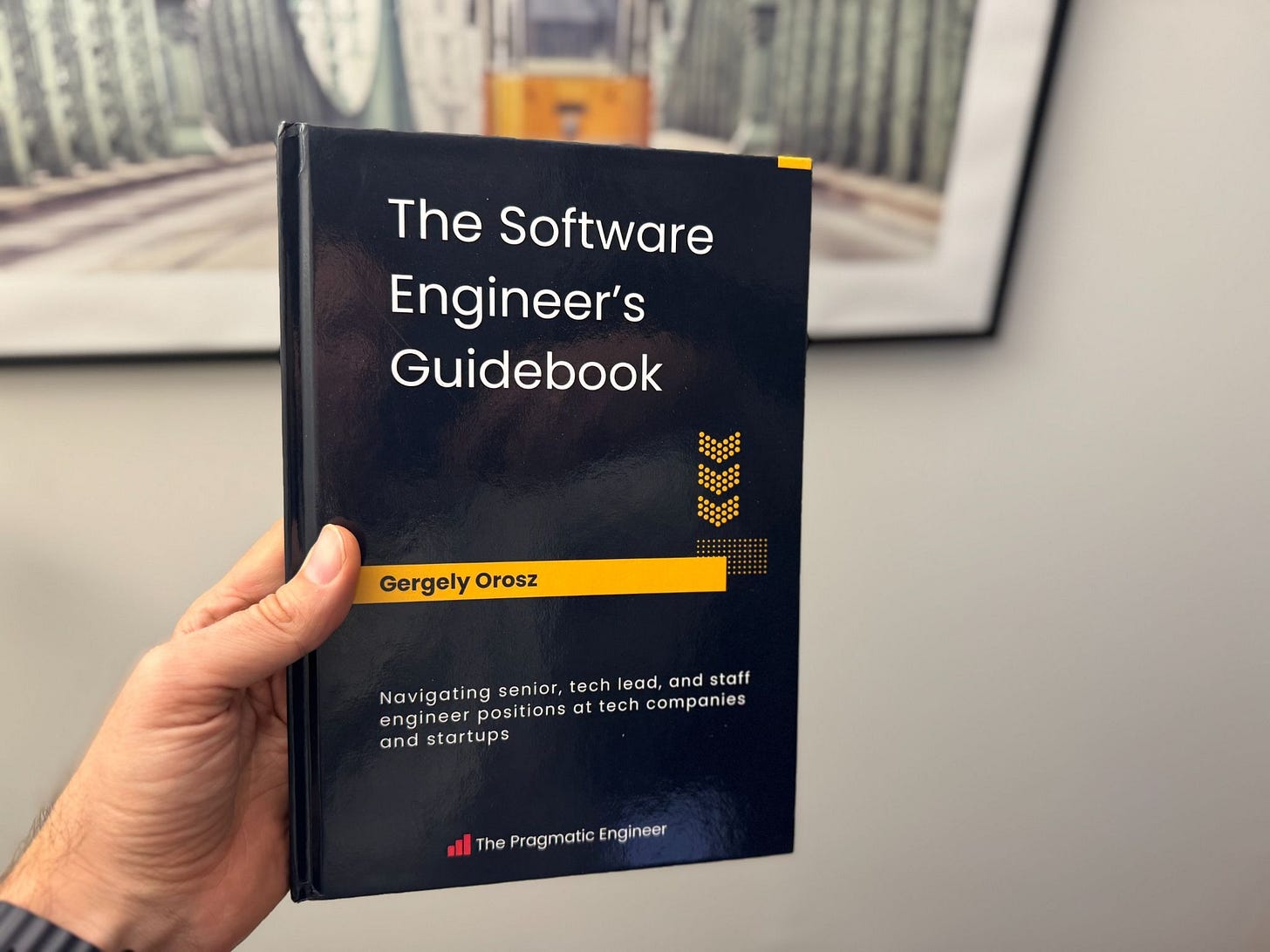

Two years ago almost to the day, I published The Software Engineer’s Guidebook. Originally, it came out in paperback, then as an ebook and an audiobook. I’m happy to share that it is now available as a hardcover, and is also on the O’Reilly platform.

Today, I’d like to draw back the curtain on the process of writing a book as a techie:

Pitching to publishers. And why I ended up breaking up with a publisher.

Self-publishing. The tools I used for writing and the platforms I published on.

Traveling to Mongolia to meet the startup which translated the book. A 30-person startup called Nasha Tech translated the book for the benefit of their company and the Mongolian tech ecosystem.

How much did my book earn? $611,911 in two years from royalties on 40,000 copies sold, to date. We need more good books in tech, so I hope that sharing these numbers inspires other techies to write them.

Learnings from writing my book. It’s hard to judge a book’s impact, but good books stay valuable for longer – that’s why they’re hard to write.

1. Pitching to publishers

In late 2019, I was an engineering manager at Uber, the ridesharing app. For the first time in my career, I was a manager of managers: suddenly, I had “skip level” software engineers, and it was here that the inspiration came to write a book that provides some advice and observations for these tech professionals.

During a 1:1 catchup with a new joiner skip-level engineer, they asked about getting up to speed in the workplace faster. They were at the Software Engineer 2 (L4), and wanted to figure out how to get to the Senior engineer level (L5A at Uber). I thought it would’ve been nice to give them a book with a bunch of pointers about what it takes to become an effective software engineer in this environment.

With that inspiration to write a book about professional growth at large tech companies and startups, I looked for publishers who could help make it a reality. I pitched my book to 3 publishers behind the highest quality tech books in the industry – O’Reilly, The Pragmatic Bookshelf, and Manning. O’Reilly and The Pragmatic Bookshelf passed, but Manning said yes.

I learned a lot by working with a publisher: the process of preparing a book to be ready for sale is much more involved than I’d assumed! I even came to appreciate why publishers may keep up to 85-90% of sales revenue, with authors typically getting 7-15% of royalties from print sales.

The chart below sets out the publication process at a typical tech book publisher, from the author pitching their idea for a book, all the way through to its launch:

Unfortunately, after three months with Manning and one editorial review, it was clear that the publisher and my book weren’t a good match. At the time, Manning had a very opinionated template for creating books which I felt pushed my own in a direction I wasn’t happy with: I felt the book would be dumbed down, and that following some of the guidance would weaken it. Also, I was less comfortable with some of the conditions and feared my hands could be tied if I wanted to share draft material online,. Also, I would not be able to choose the book title. So, we parted ways. You live and learn!

I shared more details about my experience of working with publishers in this article, including the financials of choosing a publisher as a writer.

2. Self-publishing

The biggest downside of not having a publisher is the lack of deadline pressure. Below is the rough structure I used for writing my book:

Getting the idea and the motivation

Rough outline

Procrastination about the topic

Table of contents

Writing the draft – the longest part of all

Copyediting

Content feedback

Final copyedit

More procrastination about the final draft

Production layout editing: getting the book ready for print

Cover design

Test printing

Launch planning

Launch!

Weighted table of contents

One very useful thing I took from Manning’s process is to start the book with a table of contents, where you estimate the rough number of pages one section will be about. This is helpful because the published version should not be too long or too short, so this helps set its scope and how topics should be tackled.

Here is an example of the weighted table of contents for one chapter:

This exercise resembled estimating the size of a piece of work during the planning for a software project, and provided a sense of what the longer and shorter parts of the book would be.

Write, write, write

The biggest part of writing a book is… writing it. I tried to have some regular cadence of writing, but struggled to get into one. I ended up making progress in bursts, and shared drafts on social media – like this one on healthy and unhealthy teams. This generated more ideas and I continued writing.

It’s easy to get distracted and procrastinate. A 400-page book is too large a project to take on in one go, and sometimes parts of the book change shape: an estimated 4 pages on something can turn into 20 pages a week later. It was like treading water: not making much progress with the book as a whole and being distracted by interesting topics.

Starting The Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter to finish the book

Two years into writing the book, its completion was forever 6 months away. I realized my writing process, with no publisher involved, was inefficient and unfocused.

In August 2021, I started The Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter with the hope that writing a weekly newsletter would speed up completion of the book. My thinking was to send out a draft version of a part of the book as a newsletter every few weeks.

The idea was sound, but I quickly realized that online newsletter issues can be a lot more in-depth than a chapter in a book can be, due to the issue of space constraints. Also, newsletters are timely by nature (covering what’s happening, right now), whereas a book often covers ideas that remain relevant for years.

I am thankful to have started The Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter, but doing so didn’t hasten the publication of The Software Engineer’s Guidebook. It actually delayed it by another two years.

Tools I used for self-publishing

There’s many tools available for writing a book, not including new AI tools for generating ideas – or even doing the writing in certain cases. Here’s the tools I chose:

Writing process: Google Docs and Craft. Most of my drafts were in Google Docs, and all my ideas and notes went into Craft.

Creating an ebook: Vellum. A one-off purchase, which helps generate e-book and print versions. I didn’t use it for print generation, as the software seems to be optimized for fiction.

Print layout: Overleaf. The PDF layout for print took significant effort, as I wanted to have an index in the end of the book. I ended up hiring a LateX expert who helped create a nice print layout, which would have been challenging for me to do, and time-consuming to learn.

Reader feedback: Betabooks. I wasn’t entirely satisfied as it’s pretty janky to use. In hindsight, sharing drafts in Google Docs and letting readers add comments might have been equally effective.

ISBN numbers: when self publishing, you need to purchase your own ISBN and these depend on your region. ISBN Services is a popular choice for the US. I’m residing in the Netherlands, so used the Dutch Mijn ISBN.

Book cover design: Canva. Lots of templates to work with, and it’s easy to work with the exact size requirements for print covers, as well. The cover you see today is my wife’s work.

Publishing platforms

I publish my books on these platforms:

Print book: Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) and Ingram Spark. Amazon covers most countries – but not all; notable gaps include India. Ingram Spark allows libraries and bookshops to order the book. If your title is not expected to be highly popular, Amazon KDP will probably be more than sufficient for print distribution.

Ebook: Gumroad (to sell the ebook DRM-free), Amazon KDP, Kobo Store, Google Play, and PublishDrive. Publishdrive is a neat service that publishes ebooks and audiobooks to all large and small platforms. In hindsight, I’d probably just use them to publish to all major platforms.

Audiobook: Voices (formerly: Findaway Voices). For some strange reason, Amazon’s audiobook platform (ACX) only allows residents of the US, Canada, UK, and Ireland, to publish on it. Being a resident in the Netherlands, I had to go with a third-party platform to publish to Amazon. Voices used to be owned by Spotify, and has been spun out into its own company. If I published today, I’d likely just go with PublishDrive for my audiobook, as well.

There’s a long tail of ebook and audiobook platforms, and it makes sense to use an aggregator service that publishes to most, if not all of them, and which then sends a combined payout, instead of lots of small payments from each platform.

Don’t forget the launch

Going with a publisher has the benefit that they coordinate launch activities, and also list your book on their New Releases pages, which leads to added awareness. Superior publishers also reach out to potential reviewers, and are hands-on in helping with the launch.

I knew I couldn’t count on launch support, so built a landing page where I collected emails of people who wanted to know when the book was released. To incentivize this, I provided details about the book, and the table of contents.

In hindsight, this was one of the best things I did: a good chunk of sales at launch came from people who received the email that the book was ready for purchase. Here’s how the book’s website looked, back then.

Another approach that worked well was having a dedicated social media account for the book, where I shared drafts while working on certain chapters. I was surprised by how many reshares a page or two of the work-in-progress book got, like this one.

Still, the biggest benefit of sharing drafts was that I got nearly as much feedback from social media users as from beta readers.

Procrastination is real – deal with it

Writing “the book” I’d always wanted made me freeze at times: it was something I’d never done before, it was a large project, and I wanted to get everything right.

In the end, as with software, “done is better than perfect”. Just like when working on a big software launch, the best way to make progress is to forget about how many people might use the product, and to just focus on the next task to complete… then the next… then the next.

It was amusing to remind myself that tech products I’d worked on were used by many times more people than the book could ever hope to reach – so why procrastinate? Plus, mistakes can be fixed with ebooks, they are trivial to do with a re-publish. Of course, this isn’t possible in the same way with print books, but print-on-demand means issues can be resolved in future copies.

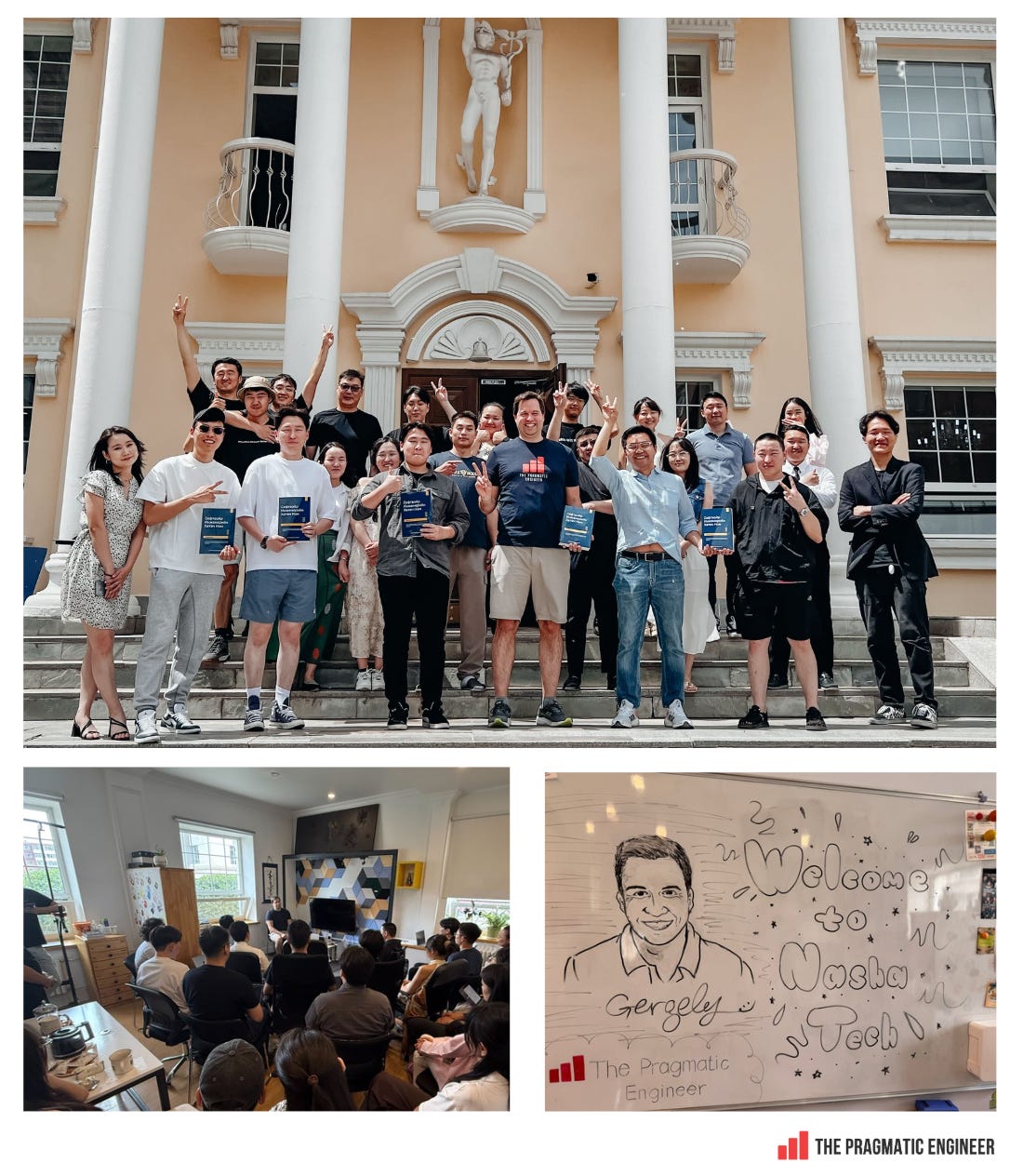

3. Traveling to Mongolia to meet the startup which translated my book

An unexpected highlight of publishing the book was ending up in Mongolia in June of this year, at a small-but-mighty startup called Nasha Tech. This was because the startup translated my book into the Mongolian language. Here’s what happened:

A little over a year ago, a small startup from Mongolia reached out, asking if they could translate the book. I was skeptical it would happen because the unit economics appeared pretty unfavorable. Mongolia’s population is 3.5 million; much smaller than other countries where professional publishers had offered to do a translation (Taiwan: 23M, South Korea: 51M, Germany: 84M people).

But I agreed to the initiative, and expected to hear nothing back. To my surprise, nine months later the translation was ready, and the startup printed 500 copies on the first run. They invited me to a book signing in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar, and soon I was on my way to meet the team, and to understand why a small tech company translated my book!

Japanese startup vibes in Mongolia

The startup behind the translation is called Nasha Tech; a mix of a startup and a digital agency. Founded in 2018, its main business has been agency work, mainly for companies in Japan. They are a group of 30 people, mostly software engineers.

Their offices resembled a mansion more than a typical workplace, and everyone takes their shoes off when arriving at work and switches to “office slippers”. I encountered the same vibe later at Cursor’s headquarters in San Francisco, in the US.

Nasha Tech found a niche of working for Japanese companies thanks to one of its cofounders studying in Japan, and building up connections while there. Interestingly, another cofounder later moved to Silicon Valley, and advises the company from afar.

The business builds the “Uber Eats of Mongolia”. Outside of working as an agency, Nasha Tech builds its own products. The most notable is called TokTok, the “UberEats of Mongolia”, which is the leading food delivery app in the capital city. The only difference between TokTok and other food delivery apps is scale: the local market is smaller than in some other cities. At a few thousand orders per day, it might not be worthwhile for an international player like Uber or Deliveroo to enter the market.

The tech stack Nasha Tech typically uses:

Frontend: React / Next, Vue / Nuxt, TypeScript, Electron, Tailwind, Element UI

Backend and API: NodeJS (Express, Hono, Deno, NestJS), Python (FastAPI, Flask), Ruby on Rails, PHP (Laravel), GraphQL, Socket, Recoil

Mobile: Flutter, React Native, Fastlane

Infra: AWS, GCP, Docker, Kubernetes, Terraform

AI & ML: GCP Vertex, AWS Bedrock, Elasticsearch, LangChain, Langfuse

AI tools are very much widespread, and today the team uses Cursor, GitHub Copilot, Claude Code, OpenAI Codex, and Junie by Jetbrains.

I detected very few differences between Nasha Tech and other “typical” startups I’ve visited, in terms of the vibe and tech stack. Devs working on TokTok were very passionate about how to improve the app and reduce the tech debt accumulated by prioritizing the launch. A difference for me was the language and target market: the main language in the office is, obviously, Mongolian, and the products they build like TokTok also target the Mongolian market, or the Japanese one when working with clients.

One thing I learned was that awareness about the latest tools has no borders: back in June, a dev at Nasha Tech was already telling me that Claude Code was their daily driver, even though the tool had been released for barely a month at that point!

Why translate the book into Mongolian?

Nasha Tech was the only non-book publisher to express interest in translating the book. But why did they do it?

I was told the idea came from software engineer Suuribaatar Sainjargal, who bought and enjoyed the English-language version. He suggested translating the book so that everyone at the company could read it, not only those fluent in English.

Nasha Tech actually had some in-house experience of translation. A year earlier, in 2024, the company translated Matt Mochary’s The Great CEO Within as a way to uplevel their leadership team, and to help the broader Mongolian tech ecosystem.

Also, the company’s General Manager, Batutsengel Davaa, happened to have been involved in translating more than 10 books in a previous role. He took the lead in organizing this work, and here’s how the timelines played out:

Professional translator: 3 months

Technical editor revising the draft translation: 1 month

Technical editing #2 by a Support Engineer in Japan: 2 months

Technical revision: 15 engineers at Nasha Tech revised the book, with a “divide and conquer” approach: 2 months

Final edit and print: 1 month

This was a real team effort. Somehow, this startup managed to produce a high-quality translation in around the same time as it took professional book publishers in my part of the world to do the same!

A secondary goal that Nasha Tech had was to advance the tech ecosystem in Mongolia. There’s understandably high demand for books in the mother tongue; I observed a number of book stands selling these books, and book fairs are also popular. The translation of my book has been selling well, where you can buy the book for 70,000 MNTs (~$19).

Book signing and the Mongolian startup scene

The book launch event was at Mongolia’s startup hub, called IT Park, which offers space for startups to operate in. I met a few working in the AI and fintech spaces – and even one startup producing comics.

I had the impression that the government and private sector are investing heavily in startups, and want to help more companies to become breakout success stories:

IT Park report: the country’s tech sector is growing ~20%, year-on-year. The combined valuation of all startups in Mongolia is at $130M, today. It’s worth remembering that location is important for startups: being in hubs like the US, UK, and India confers advantages that can be reflected in valuations.

Mongolian Startup Ecosystem Report 2023: the average pre-seed valuation of a startup in Mongolia is $170K, seed valuation at $330K, and Series A valuation at $870K. The numbers reflect market size; for savvy investors, this could also be an opportunity to invest early. I met a Staff Software Engineer at the book signing event who is working in Silicon Valley at Google, and invests and advises in startups in Mongolia.

Mongolian startup ecosystem Map: better-known startups in the country.

Two promising startups from Mongolia: Chimege (an AI+voice startup) AND Global (fintech). Thanks very much to the Nasha Tech team for translating the book – keep up the great work!

4. How much did my book earn?

There’s usually little information about the key topic of how much authors make from their books being published, beyond “not much”. Author Justin Garrison shared that his co-authored title Cloud Native Infrastructure earned $11,554 in its first year – and without three unexpected sponsorships, that amount would’ve been $3.500. Conventional wisdom states you should not write a book for money, but for the other benefits like building your status as an expert in a domain, or exploring a topic in more depth.

A notable exception to this rule is Designing Data Intensive Applications, whose author Martin Kleppman made $477,916 in royalties in the first 6 years of publication, as he shared. Martin published with O’Reilly, and the book sold 108,000 copies, generating around $4.50 per copy in royalties for the author. Still, Designing Data Intensive Applications is one of the most successful books, and Martin argues that a book’s real value lies in the value it creates:

“Writing a book is an activity that creates more value than it captures. What I mean with this is that the benefits that readers get from it are greater than the price they paid for the book. To back this up, let’s try roughly estimating the value created by my book.

It’s hard to quantify that, but let’s say that the people who applied ideas from the book avoided a bad decision that would have taken them one month of engineering time to rectify. (I’d actually love to claim that the time saving is much higher, but let’s be conservative in our estimates.) Thus, the 10,000 readers who applied the knowledge freed up an estimated 10,000 months, or 833 years, of engineering time to spend on things that are more useful than digging yourself out of a mess.

If I spend 2.5 years writing a book, and it saves other people 833 years of time in aggregate, that is over 300x leverage. If we assume an average engineering salary on the order of $100k, that’s $80m of value created. Readers have spent approximately $4m buying those 100,000 books, so the value created is about 20 times greater than the value captured. And this is based on some very conservative estimates.”

The Software Engineer’s Guidebook will probably be another exception; it has sold 40,000 copies and netted $611,911 in royalties in the two years since publishing:

Here is how revenue from different platforms adds up:

Print:

Amazon KDP: 29,806 copies, $470,000 in royalties ($16 per book)

Ingram Spark: 1,316, copies, $10,322 in royalties ($8 per book)

Ebooks:

Kindle: 3,909 copies, $42,992 royalties ($11 per book)

DRM-free ebooks: 2,713 sales, $54,963 royalties ($20 per book).

Other ebooks: 388 copies, $6,882 in royalties ($17 per book). 90% of sales came from iTunes, Google Play and Kobo.

Audiobook:

Amazon, Spotify, and other platforms: unclear how many purchases, $6,511 royalties (Audible typically pays around $1.50-3.50 per audiobook, Spotify closer to $9)

DRM-free ebook: 241 sales, $3,241 royalties ($13 per book)

I previously shared more about how I created the audiobook

Translations:

5 languages, $17,000 in upfront royalty payments (South Korea: $5,000, Japan: $4,500, Germany: €3,000, Taiwan: $2,000, China: $2,000)

Total: $611,911 in royalties, circa 40,000 in copies sold (38,373 copies, plus audiobooks, plus foreign translations that don’t have exact numbers)

These are good numbers for a tech book, and it enjoyed the advantage of being published after The Pragmatic Engineer newsletter found an audience online. Thank you to everyone who purchased a copy of the book or gifted one!

It’s interesting, as someone who self-published print and audiobook versions of their title, that royalties per book sold are highest in paperback, and much lower for the ebook and the audiobook. This is because Amazon takes 70% of the purchase price of the Kindle ebook, and 75% for the audiobook, but only 40% for the print book, in marketplace fees.

Self-publishing definitely helped substantially increase the royalties generated from the book, which would be 4-8x lower if done via a publisher. At the same time, self publishing increased the amount of time and effort I needed to invest.

5. Learnings from writing my book

The impact of a book is hard to know with certainty. When I publish a newsletter article or a podcast episode, the feedback is almost immediate: I get comments, emails, and mentions about the contents for a few days – perhaps a week or two. After that, I rarely hear feedback again.

But I run into people at events and conferences who say the book helped them focus more on their career, or get a desired promotion to senior-or-above.

A lot more readers than expected find the book via recommendations or gifting. I hear stories about my book being recommended or purchased for engineers by managers, or peers, or friends – and then they felt obliged to start to read it. This kind of dynamic also exists with articles and podcast episodes, but my sense is that being given a book is a very strong nudge to invest time in the resource.

Good books stay valuable for longer – that’s why they’re hard to write. The final 18 months of writing the book mostly involved editing the existing draft. I tried to remove details that were likely to age poorly in the near to medium term future – like mentions of specific frameworks, or things that felt like short-lived fads (e.g: “web3” engineering as a category, which seems to have mostly vanished from the discourse.

Even so, I got burnt by the fast-changing nature of tech. In my last edits, I added short sections on AI, about how it’s a useful tool to learn languages with, or for getting unstuck. I gave examples of tools that were popular in 2023, and predicted they would remain relevant: ChatGPT, GitHub Copilot, and Google Bard. I figured that OpenAI would be around for at least 5 years, and that Microsoft and Google know how to name their products.

I was wrong: Google renamed Bard to Gemini four months after my book was published. In response, I removed all product mentions from an updated version of the book: who knows when the search giant will change the name again!

Amazon’s print-on-demand service is incredibly good. Amazon prints books on demand in 10+ markets, and ships these on-demand books to even more countries. Books printed this offer the highest price-per-value across all print-on-demand services I found. Amazon’s KDP is considerably more price efficient compared to the other major print-on-demand player, Ingram Spark.

One paperback copy of my book (a 413 page book) costs $8 to print with Amazon. With Ingram Spark it’s double this: $16! This is a massive difference in printing costs that is hard to ignore, and is one reason to choose Amazon’s print-on-demand service as primary distribution for print books. This explains why my royalties per book are $16 with Amazon prints, and $8 with Ingram Spark prints.

Ebook, audiobook and print sales reporting feels stuck in the 1990s. Both ebooks and audiobooks are digital products, so you’d expect it would be possible to get near-real time sales data. But the reality is that it’s not: audiobook platforms like Spotify and Audible release reports monthly (as I understand), and good luck trying to figure out which sales equate to what! This is after Audible takes 80% from sales.

Ebook reporting is similarly slow, due to sales being reported in a delayed fashion. There are so many audiobook and ebook platforms to buy on that it’s only sensible to use an aggregator like Publishdrive or Voices. This adds one more layer of abstraction and more reporting delays. I understand that print sales take months to be reported, but did not expect it to be the case with audiobooks.

Even today, I have no idea how to find out how many people have listened to the audiobook, and by now I would have hoped for better reporting. It shows that if there are few suppliers in a segment (like audiobook publishers, who use these reporting tools) and not much competition: companies can get away with poor tooling.

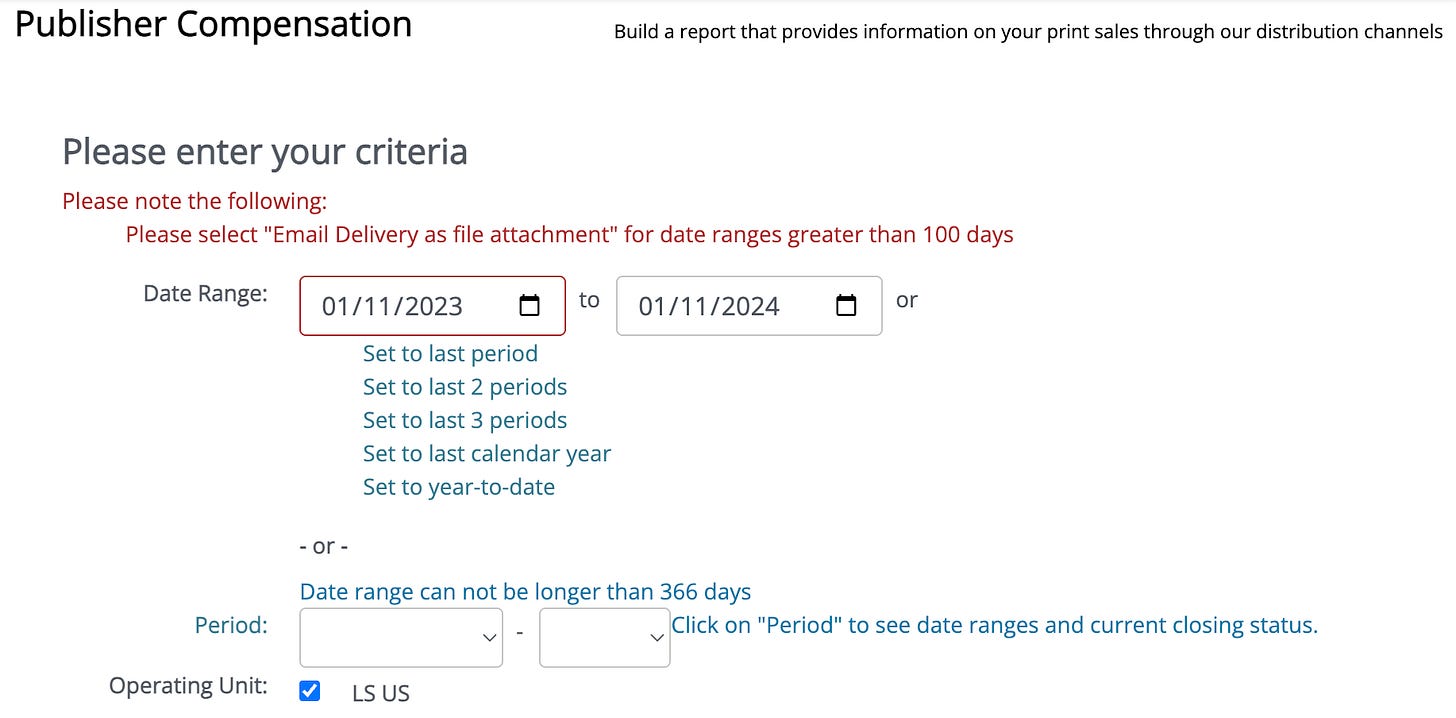

Print reporting is perhaps even more unusable. Ingram Spark is one of the biggest print-on-demand providers - but it’s not possible to get a report about a sales period longer then a year. The cherry on the cake is how if you query a period longer than 100 days, they can only email these reports:

This is a portal that has had no usability testing — and customer seem to put up with it:

Amazon has an unhealthy monopoly on the audiobook and ebook sectors. Amazon generated more revenue from books sold on its site than I did, as a self-published author:

75% of revenue for all audiobooks sold via Audible

70% for all Kindle ebooks

40% for all print books as Amazon marketplace fees

That Amazon has a take rate of 75% for audiobooks and 70% for Kindle ebooks (those priced above $10) and still controls most of the market, makes this segment look like a monopoly. I offer my ebooks and audiobooks as DRM-free versions, and am happy to see more customers choose these options over the Kindle or Audible ones. Still, market forces alone don’t feel strong enough to challenge Amazon’s dubious pricing and practices. I wrote more about Amazon’s monopolistic audiobook practices.

Looking back on the experience of writing my book, it was worth it for the thinking and organization that it forced on me. It has been an unusually long professional project that stretched across four years and I’ve learnt a lot from the process: it forced me to think deeply about topics like the importance of software architecture, and figuring out how a business works, as a Staff+ engineer. It forced me to rewrite and refine my ideas multiple times, and with each rewrite came fresh ideas and a clearer understanding of the subject. This is what really matters for software engineers to progress professionally in the industry, I believe.

Ultimately, I hope the book generates more “wealth” by helping out devs in a career rut, or who are seeking inspiration to get stronger as engineers. Obviously, commercial success is nice – and I shared those numbers in the spirit of transparency because I believe in the value of detailed, in-depth, and thoroughly researched and written information. Every anecdote helps dispel the myth that books cannot be decent earners for their authors.

If you’re in the process of writing a book, why not get in touch about doing a guest post in this publication? Personally, I’ve found guest posts tend to be a good fit for engineers midway through writing a book!

Great article - thanks! I found some really high quality editors & cover designers on Fiverr for a decently low price point. I'd recommend that as a tool for folks in the self-publishing process.

Almost done with Mastering Behavioral Interviews, making the final push for the end of November deadline. A lot of this resonates with me, especially the bursty progress---for me, integrating book writing with my family's other activities and our primary business was challenging.

I turned to some motivational hacks to keep me moving, like completing parts of the writing process out of order (cover, layout, website before final draft). I even ordered a pre-print to see what progress felt like in my hand. All of that kept the wind in my sails.