What is good software architecture?

What good architecture looks like, how to improve your skill at building it –and why Architects are not always the answer. Guest post by Matthew Hawthorne, who built large systems at Netflix & Twitter

To try and answer this seemingly basic question, I turned to software engineering veteran Matthew Hawthorne. He’s worked as a software engineer for more than 25 years, and is the author of the upcoming book Push to Prod or Die Trying, which shares lessons from the trenches on software, architecture, and pushing to production. It is in early release now and due to be published next year.

Matt has worked at Comcast, Twitter, and Netflix, where he stayed for 6 years during the 2010s. During his time at Netflix, every engineer made architectural decisions day-to-day and shipped features frequently, which rolled out to tens of millions of users – all without a single mention of the job title “Architect”.

In this issue, Matt covers:

Architects are not the solution to architectural problems. For a long time, there were no Architects at Netflix, yet the foundations of the architecture were still sound.

Trading off today’s problems for tomorrow’s: migrating to AWS. Moving to the AWS cloud created plenty of problems for Netflix which took serious effort to resolve, down the line. But it also fixed existing pain points.

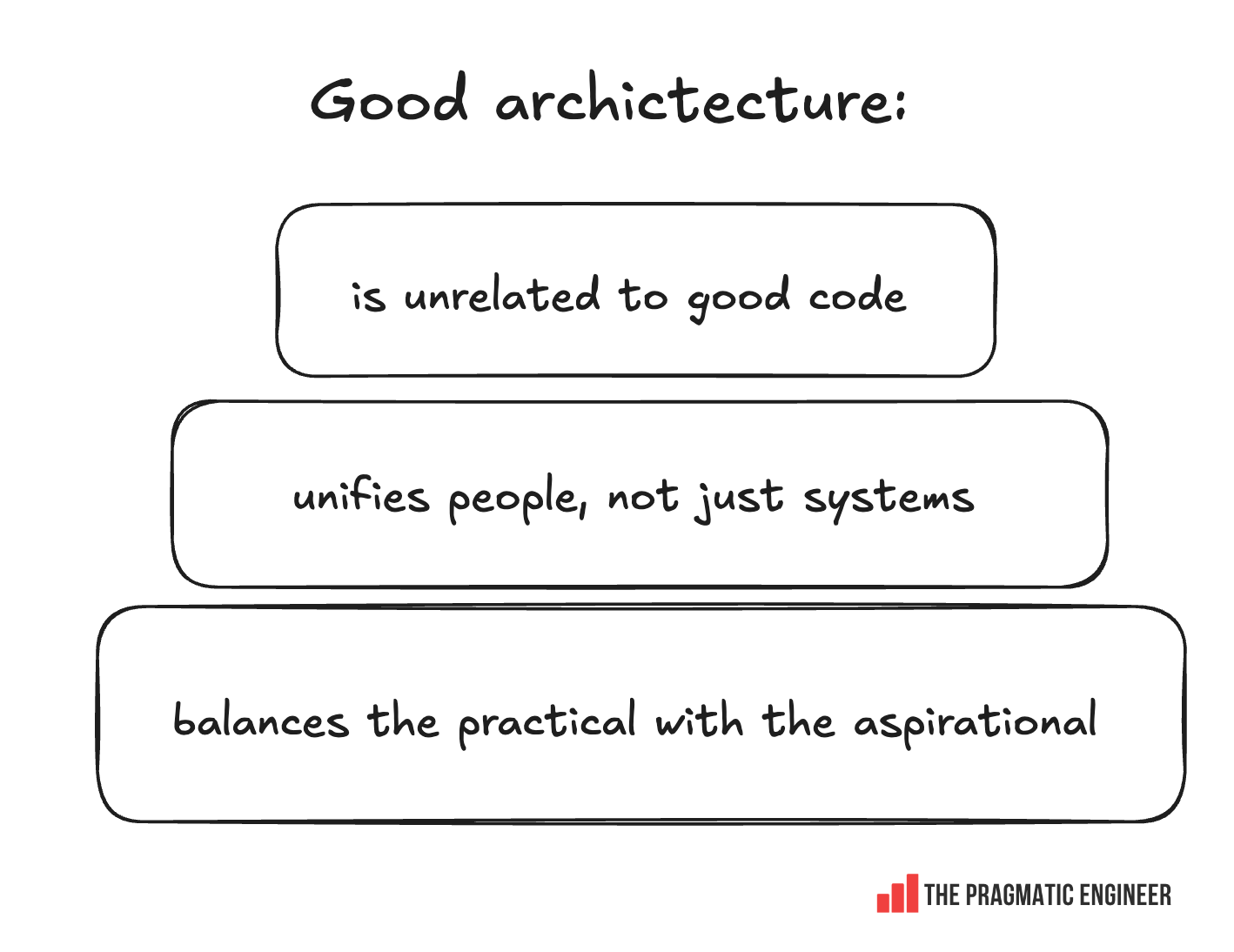

Good characteristics of architecture. These balance practical and aspirational concerns, unify people as well as systems – and are unrelated to good code.

Bad architecture is a lot of work that doesn’t change much. It’s like rearranging the furniture in a house that should be demolished and replaced by an improved layout.

Good architectural trades in Netflix projects. Making unusual tradeoffs, building tooling to reduce operational work, trading off one set of limitations for another, and upgrading systems to work better in the future.

How to improve your architecture skills. Design systems based on what could break, know your audience, focus on the right details, and make yourself valuable across several roles.

If you’d like to keep up with Matt’s writing, subscribe to his newsletter, Push to Prod. You can also purchase his work-in-progress book Push to Prod or Die Trying, which is currently 40% complete.

With that, it’s over to Matt:

At Netflix, we preferred building prototypes to writing formal architecture proposals, while at other companies, I’ve seen impractical architecture proposals fail, overly practical architectural efforts succeed – but then deliver limited impact – and other proposals gather dust due to the absence of the conversations and alignment work necessary for creating a shared plan.

I’ve always found the work defined by the phrase software architecture to be vague, and the value delivered by capital “A” Architects to be debatable. I speak from personal experience here after my own brief, unimpressive tenure as a “domain architect” – an experience from which I learned much, but delivered very little. Over time, if there’s one thing I’ve learned about architecture, it is that:

Good architecture work is about purposefully trading problems you have today, for better problems tomorrow. Basically, if you’re not upgrading your problems, you’re just rearranging furniture.

1. Architects are not the solution to architectural problems

I worked at Netflix for 6 years and during that time, there were hundreds of things that made the company unique. One was the lack of software architects – in title – at least. In fact, we didn’t have engineering levels at all; every engineer was a Senior Software Engineer.

I spent my first 4 years there on the Edge team, which was around 20 engineers building and operating a software layer that sat between client devices and backend services. “Edge” in this case was the edge of Netflix’s server infrastructure, which carried a heavy operational burden.

It felt like the first step in every production incident was for us to prove we weren’t to blame for it. This was annoying but effective; colleagues assumed that if every client request goes through our system, then we must have logs or metrics captured by our system that identify and clarify problems. We often did, and when we didn’t, we worked to close the gaps. Of course, sometimes we did cause incidents, and on occasion, “we” was “me”.

Over a few years, we solved the most pressing problems by increasing resiliency, building flexible edge routing, and enabling predictive autoscaling. If I reflect on these projects and others from my time at the video streaming giant, there wasn’t architecture in the sense that I’d seen before. Those who proposed ideas also did the work, which avoided the awkward white-collar vs. blue-collar split that often arises between architects and engineers in tech workplaces. Most technical ideas originated in the “trenches”, resulting in deliberate architectural choices with obvious value. Over time, we entered a new era that involved extensive conversations about creating massive new systems to solve imaginary future problems, instead of real, present ones.

A new behavioral archetype formed at the company – the “Architect”. I am talking about engineers who hovered around the work, pushed new ideas, and didn’t make material contributions to day-to-day struggles. They weren’t on our on-call rotations, ostensibly because their managers wanted to give them more time to brainstorm new ideas, so they had ample time for conversations and intellectual enquiry, while the rest of us did grimy, operational work. Over lunch one day, a colleague and I discussed the situation. “I’m not sure what the solution is”, I said. “The solution”, he replied, “is to not have architects.” I laughed, then realized he wasn’t joking.

I thought Netflix didn’t need architects, and considered this more broadly: does any company really need them? Let’s examine why the role of Architect exists. I believe it’s an artifact of the old-school waterfall fantasy:

Design: Architects think big thoughts and draw diagrams

Build: Engineers turn diagrams into code

Test: QA finds bugs

Operate: Ops keeps the systems running smoothly

These four phases are inescapable, and every company approaches them in its own unique way. Imagine an axis: on the left, there’s a distinct role for each phase, and on the right, there’s a single role performing them. Every company lives somewhere on this axis.

For example, the shift towards agile at big companies made “big design, up front” less popular, and often combined Design and Build into a single, continuous phase. And the shift towards cloud, DevOps, and the “you write it, you run it” model often blends Build, Test, and Operate into a single phase.

So, why did Netflix introduce architects? My perception is that this was related to scope: our management chain believed we needed bigger, bolder ideas to redefine how our systems worked, and that those tasked with achieving this needed distance from day-to-day work.

It sounds perfectly logical, but I’ve never seen it work. I didn’t try to fix it – I switched teams and moved to the Personalization Infrastructure group, a domain I’d always been interested in. This team was newer and they were solving concrete problems. As I understand, the Edge team continued on the path of re-visualizing their platform with great success.

On a long enough timeline, success breeds specialization. You solve the hardest problems and management asks, “What’s our 3-year vision?”. Distinct groups emerge of “thinkers” and “builders”, and many companies formalize this with Principal or Staff Engineers who function as architects in all but name. From what I’ve seen, it is hard for people in these roles to avoid becoming disconnected from reality: their minds are powerful, but structure and incentives make it difficult to find appropriate targets.

2. Trading off today’s problems for tomorrow’s: migrating to AWS

The most significant tradeoff I saw at Netflix involved a decision that predated my time there: moving the company’s entire infrastructure to AWS. “So what?” you may think; lots of companies run everything in AWS.

Sure, lots of companies do so today, but none of significant scale did in 2010. I recall reading a few blog posts about Netflix’s AWS migration before I joined, and thinking, “they’re insane.” But after I joined and saw the situation up close, it made a lot of sense.

What are the repercussions of running in a datacenter, on-prem, non-cloud environment?

Stable networking and hardware.

Fixed capacity constraints. Perhaps not permanently fixed, but capacity can be increased as fast as machines are purchased, racked, and put online.

What are the consequences of running in AWS or other cloud environments?

Virtually unlimited, elastic capacity.

Unstable networking and hardware. If “unstable” sounds harsh, let’s call it “much less stable than desired.”

If that was everything, then the business case for elastic capacity was strong enough to declare the AWS migration a solid trade. But from the perspective of the Edge team, this trade sent us down a path of many other problems.

For example:

Obsessing over resiliency by building libraries to implement circuit breakers, concurrency limits, and fallbacks, as well as dashboards to observe this behavior in real time.

Detecting and terminating bad AWS instances.

Refining service discovery and software load balancing for hundreds of elastic clusters.

Fine-tuning reactive autoscaling policies.

Abandoning reactive autoscaling and building a predictive autoscaling system from scratch.

These were problems we wouldn’t have had if we’d stayed in the data center. But they were also exponentially better than having fixed-capacity software and constrained customer growth. This was not only a good tradeoff for the business – it also catalyzed a planet-scale improvement of our engineering capabilities.

3. Good architecture characteristics

Let’s discuss a few characteristics of good and bad architecture work.

Good architecture is unrelated to good code

Very early in my career, I sat in a meeting and watched a newly hired, experienced engineer draw manically on a whiteboard for 30 minutes. I had no idea what he was talking about, but he was highly respected by senior teammates, so I paid close attention.

A few weeks later, I had some free time and we paired up to prototype some of his ideas. His code was atrocious and he had a hard time getting anything to work. But he said something which struck my young mind as profound:

“We’ve got SQL queries hardcoded into the UI”, he said. “We should change that so that the UI calls a service which abstracts the query behind a concept, like ‘get all items for the current user’”.

That’s a great idea, I thought. Over the next few years, I learned a ton from him about testing, separation of concerns, hot and cold storage, compression, data formats and schemas, and more. But I never reconciled how a person so bad at writing code could have such solid ideas about system design. A larger point emerged:

Someone’s ability to write high-quality code is entirely independent of their ability to create or recognize high-quality architecture.

I’ve worked for engineering leaders who hadn’t written code in years, yet had a brilliant sense of technical fundamentals. When necessary, they grabbed the wheel and steered their teams away from expensive mistakes and towards bountiful opportunities. They didn’t have great coding skills, but possessed impeccable design sense, instincts, and taste.

I’ve also worked with engineers who were experts in various programming minutiae, yet had no clear ability to build systems that could work together coherently and functionally. Their ability to optimally implement classes or functions did not extend beyond the source files they edited.

Architecture connects systems built with code, but is a distinct discipline from coding with limited overlap. You cannot LeetCode your way into a cohesive, opportunistic architecture that serves the business.

Why not? Let’s explore the “good at architecture, bad at code” archetype. I’ve found these individuals are drawn to the most essential details. When designing a new system, they ask questions like:

What data can we collect to ensure things work correctly?

What is the maximum acceptable latency for clients of this system?

Do we need to compute results in real time, or can we do it offline in batch mode?

They are generally less concerned with details like class hierarchies, method names, and directory structures, which are trivial in the broader business and distributed systems contexts.

But code can’t be completely irrelevant, right? Let’s examine the “good at code, bad at architecture” archetype, which I think occurs when individuals haven’t had a role in which things like network latency, fallbacks, or failure modes are first-class citizens.

Note, I use the word “architecture” to mean “distributed systems architecture”, which is common and also biased towards my personal experience.

At Netflix, we’d often find that backend services had slow memory leaks, which took a long time to discover and fix because instances rarely lived longer than 48 hours, due to autoscaling policies. If we had chosen to focus on memory leaks instead of autoscaling, Netflix would have been unable to scale to meet demand, and would’ve been a much smaller business.

Good architecture unifies people, not only systems

A few years later, as a Staff Engineer at a large social media company, I led a project to build analytics for our real-time content personalization system.

The existing design had evolved from a prototype built before I joined. We generated events from our runtime systems that briefly sat in a queue before being exported into an external datastore.

These events captured information such as:

Which content was served to whom at what time

ML model scores for each user/item pair

This data enabled us to:

Track bias across different phases of personalization, from candidate generation to filtering, ranking, and serving

Investigate and debug issues, such as:

Why do some users receive empty pages with zero recommendations?

Why is some content unexpectedly served much more than others?

From a “social” point of view, there was much to consider:

My queue of stakeholders grew exponentially, as everyone suggested two other people to consult.

“We need a design” was a recurring theme among those I talked to. When I asked what goals the current design was preventing us from achieving, I didn’t receive useful answers.

There was a prototype for a competing project that a few engineers on the team felt we should use instead of the current system.

The line between what was and wasn’t “analytics” was blurry. For example, we were asked multiple times if we could log ML features along with analytics data. We always declined due to a tight schedule, but I felt that we were missing an opportunity to solve a broader, more impactful problem.

We needed a cohesive vision to get everyone on the same wavelength, so I wrote a design document to achieve this which described the problem we were solving – both business-wise and scale-wise – and added a bunch of diagrams. I presented a few options for refining the project and described what I felt was the best path, and why. Then I shared the document.

After a few weeks of conversations with the team and stakeholders, nothing improved and the situation had become notably worse. The team was more fractured than ever, with multiple sub-teams moving in different directions. The notion of a comprehensive analytics solution felt like a distant dream.

I left the company shortly after this, as I no longer felt it was the right fit. But I asked myself for months afterwards what I could have done differently to deliver a better result. I always come back to one answer:

I was too focused on solving a technical problem when the primary issue was a social one.

My job had not been to just make optimal technical decisions. It was to bring everyone together with a unifying vision, whether it was technically optimal or not.

In the video ranking case mentioned above, I lobbied for that project intermittently for over a year before work started: I presented slides and sent them to anyone I could find, gathered a bunch of data, and made more slides. Things went quiet for a while. And then, finally, the stars aligned and we started moving.

In the corporate world, objectively good ideas are rare. Ideas don’t have to be good per se; they just have to move people forward. Of course, good ideas are more likely to move people than bad ones, but in workplaces, something is “good” when the right people agree it is.

Good architecture balances the practical with the aspirational

Around the year 2020, I was working at a large US TV operator as a Principal Engineer. My role was focused on making broad improvements to personalized video ranking, and I partnered with an Architect to address the problem of making video ranking more flexible. Historically, most content was served by the product either via search, or a variety of human-curated collections. Fully personalizing our content required connecting multiple functions, systems, and teams in a new way.

Let’s talk about those teams briefly. Our primary partner was the Search team, a group of 20 or so engineers who operated a high-volume search index, along with a system to access all editorially curated content collections. Their priority was serving relevant search results in a stable, highly available way. A change to their system usually took at least a month to land in production.

We were the Personalization team, a mixture of around 10 Machine Learning Researchers and Software Engineers. We owned several services that provided personalized content to users at runtime, along with numerous data pipelines and random batch jobs. Our priority was increasing user engagement by maximizing the amount of personalized content served. If you asked us to make a change to our system, we could likely get it in production in two business days.

Our goal was to create a proposal with a high chance of winning buy-in from partner teams. One of my self-imposed constraints was that the proposal to increase personalization had to be achievable within our current responsibilities and organizational structure. We needed to increase the speed at which we could put new features and experiments into production, so we had to be mindful and realistic about the demands placed upon the slowest-moving teams.

My architect partner disagreed, saying:

“We should propose the best technical solution. And if that requires organizational changes, let the managers figure it out.”

It was an interesting idea, but at the time, a proposal requiring a reorg went nowhere fast at that company. It would also limit my opportunities to write future proposals.

In this case, the Search team moved slowly for legitimate reasons. The Personalization team moved quickly, also for legitimate reasons. One of the goals of our proposed architectural changes was to increase the speed of testing new ML models in production. If adding a new model or configuring an existing model involved manual changes and testing by the Search team, then we would continue to move slowly at their pace. To ignore this constraint would be to provide a proposal of limited value.

A common stereotype of Architects is that they propose things that don’t work in the real world. Their solutions require a new, perfect world to be constructed beforehand. In our case, a perfect world could be created by a reorg that breaks apart the Search team, or maybe by rewriting all services from scratch.

But conceiving new worlds isn’t the problem; the problem is the inability to intersect a perfect world with the one that actually exists. Sure, maybe a reorg or rewrite would be ideal, but in the meantime, can we deliver something valuable within current constraints to reveal opportunities being missed in the current state?

We were strategically exposed, and mitigated this issue via prototyping. We couldn’t win buy-in for a broad proposal, so proposed three different architectures and ran them in parallel with a small amount of real customer traffic. The option with the highest demand on the Search team performed significantly worse than the others, partially due to some architectural flaws, but mostly because they moved more slowly than the Personalization team. Production traffic is the ultimate practical differentiator.

4. Bad architecture is a lot of work that doesn’t change much

Let’s discuss the Principal Engineer role from the “Good architecture balances the practical with the aspirational” section above. I was asked to review a proposal for an “improving personalization architecture” initiative led by an engineer on a team I worked with. It was filled with clearly-stated decisions, such as: