How AWS deals with a major outage

What happens when there’s a massive outage at AWS? A member of AWS’s Incident Response team lifts the lid, after playing a key role in resolving the leading cloud provider’s most recent major outage

In October, the largest Amazon Web Services (AWS) region in the world suffered an outage lasting 15 hours, which created a global impact as thousands of sites and apps crashed or degraded – including Amazon.com, Signal, Snapchat, and others.

AWS released an incident summary three days later, revealing the outage in us-east-1 was started by a failure inside DynamoDB’s DNS system, which then spread to Amazon EC2 and to AWS’s Network Load Balancer. The incident summary overlooked questions such as why it took so long to resolve, and some media coverage sought to fill the gap.

The Register claimed that an “Amazon brain drain finally sent AWS down the spout”, because some AWS staff who knew the systems inside out had quit the company, and their institutional knowledge was sorely missed.

For more clarity and detail, I went to an internal source at Amazon: Senior Principal Engineer, Gavin McCullagh, who was part of the crew which resolved this outage from start to finish. In this article, Gavin shares his insider perspective and some new details about what happened, and we find out how incident response works at the company.

This article is based on Gavin’s account of the incident to me. We cover:

Incident Response team at AWS. An overview of how global incident response works at the leading cloud provider, and a summary of Gavin’s varied background at AWS.

Mitigating the outage (part 1). Rapid triage, two simultaneous problems, and extra details on how the DynamoDB outage was eventually resolved.

What caused the outage? An unlucky, unexpected lock contention across the three DNS enactors started it all. Also, a clever usage of Route 53 as an optimistic locking mechanism.

Oncall tooling & outage coordination. Amazon’s outage severity scale, tooling used for paging and incident management, and why 3+ parallel calls are often run during a single outage.

Mitigating the outage (part 2). After the DynamoDB outage was mitigated, the EC2 and Network Load Balancer (NLB) had issues that took hours to resolve.

Post-incident. The typical ops review process at AWS, and how improvements after a previous major outage in 2023 helped to contain this one.

Improvements and learnings. Changes that AWS is making to its services, and how the team continues to learn how to handle metastable failures better. Also, there’s a plan to use formal methods for verification, even for systems like DynamoDB’s DNS services.

Spoiler alert: this outage was not caused by a brain drain. In fact, many engineers who originally built the service, DNS Enactor (responsible for updating routes in Amazon’s DNS service) ~3 years ago, are very much still at AWS, and five of them hopped onto the outage call in the dead of night, which likely helped to resolve the outage more quickly.

As it turns out – and as readers of this newsletter likely already know! – operating distributed systems is simply hard, and it’s even harder when several things go wrong at once.

Note: if you work at Amazon, get full access to The Pragmatic Engineer with your corporate email here. It includes deepdives like Inside Amazon’s Engineering Culture, ones on Meta, Stripe, and Google, and a wide variety of engineering culture deepdives.

1. Incident Response team at AWS

Amazon is made up of many different businesses of which the best known are:

Amazon Retail: operates the shopping websites Amazon.com, and 21 regional versions including Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, and others.

AWS: everything to do with Amazon Web Services. Retail is a major customer of AWS.

These organizations operate pretty much independently with their own processes and set ups. Processes are similar but not identical, and both groups evolve how they work over time, separately. In this deepdive, our sole focus is AWS, but it could be assumed Retail has some similar functions, like separate Incident Response teams.

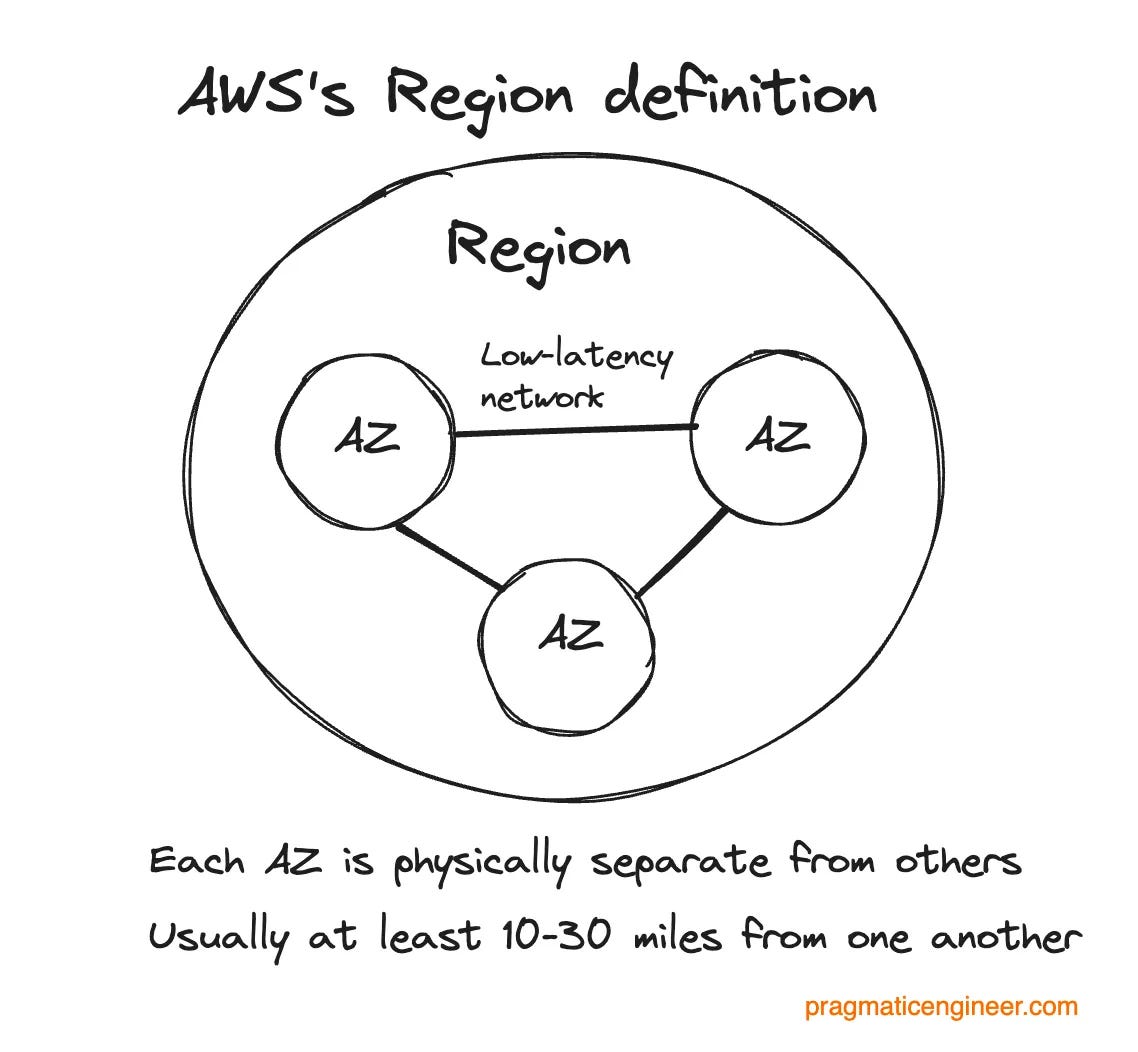

Regions and AZs: AWS is made up of 38 cloud regions. Each one consists of at least 3 Availability Zones (AZs), which are at least one independent data center, connected via a low-latency network. Note: “Region” and “AZ” mean slightly different things among cloud providers, as covered in Three cloud providers, three outages, three different responses.

Incident Response is a dedicated team at AWS, staffed by experienced support and infrastructure engineers, who do the following:

Monitor all 38 AWS regions, continuously. Health KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) are set up, so it’s easy to tell if a service is healthy or not. These KPIs vary by service, but typical ones include monitoring API success rates and response latencies, as well as synthetic canaries.

Get alerted when a region becomes unhealthy, or KPIs suggest it might be.

Coordinate incident calls when an outage happens within a region or AZ.

Oncall rotation 24/7: someone is always available to respond to an alert.

Interesting detail: the oncall team for Incident Response is distributed across Seattle, Dublin, and Sydney, which is a “follow the sun” rotation, meaning nobody is oncall when it’s nighttime where they are.

Oncall team members are a mix of senior+ engineers and relatively junior engineers onboarded after training in how to handle alerts and run calls. For significant events like this latest outage, an oncall “AWS Call Leader” is paged automatically. These are more tenured folks, usually principal up to distinguished engineers.

All AWS Service teams and products run their own independent oncall teams. The AWS Incident Response group is a “safety net” which coordinates large-scale events.

AWS has a “you build it, you run it” mentality: teams have autonomy to decide which service they build, the technologies used, and how they structure it. In return, they are accountable for the service meeting the uptime target; for production services, this means having an active oncall. We cover more about oncall practices in Healthy oncall practices, and detailed compensation philosophies in the Oncall compensation article.

Gavin’s background at AWS

For this article, Gavin McCullagh shared the story of how the incident unfolded from his point of view. Gavin joined Amazon’s Dublin office in 2011 and worked for many years as a DNS and Load Balancing Specialist, including working on Route 53 Public DNS, and Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) DNS Resolver. Nowadays, Gavin works in a team focused on Incident Response and Resilience for AWS services and customer applications. This includes the AWS Incident Response team, and services like Application Recovery Controller and Fault Injection Service.

Since his early days there, Gavin has been a regular in large-scale incident calls as his first team – Load Balancing – was regularly paged into major incidents because it is central to AWS, and telemetry from load balancers can greatly help with debugging.

2. Mitigating the outage (part 1)

All times below are in Pacific time.

19 Oct, 11:48 PM: the incident begins and regional health indicators degrade, triggering an alert. Minutes later, AWS Incident Response oncall is paged. The AWS call leader also joins the call. Gavin joins despite not actually being oncall because he figures he might be able to help – which turned out to be a good hunch.

Rapid triage

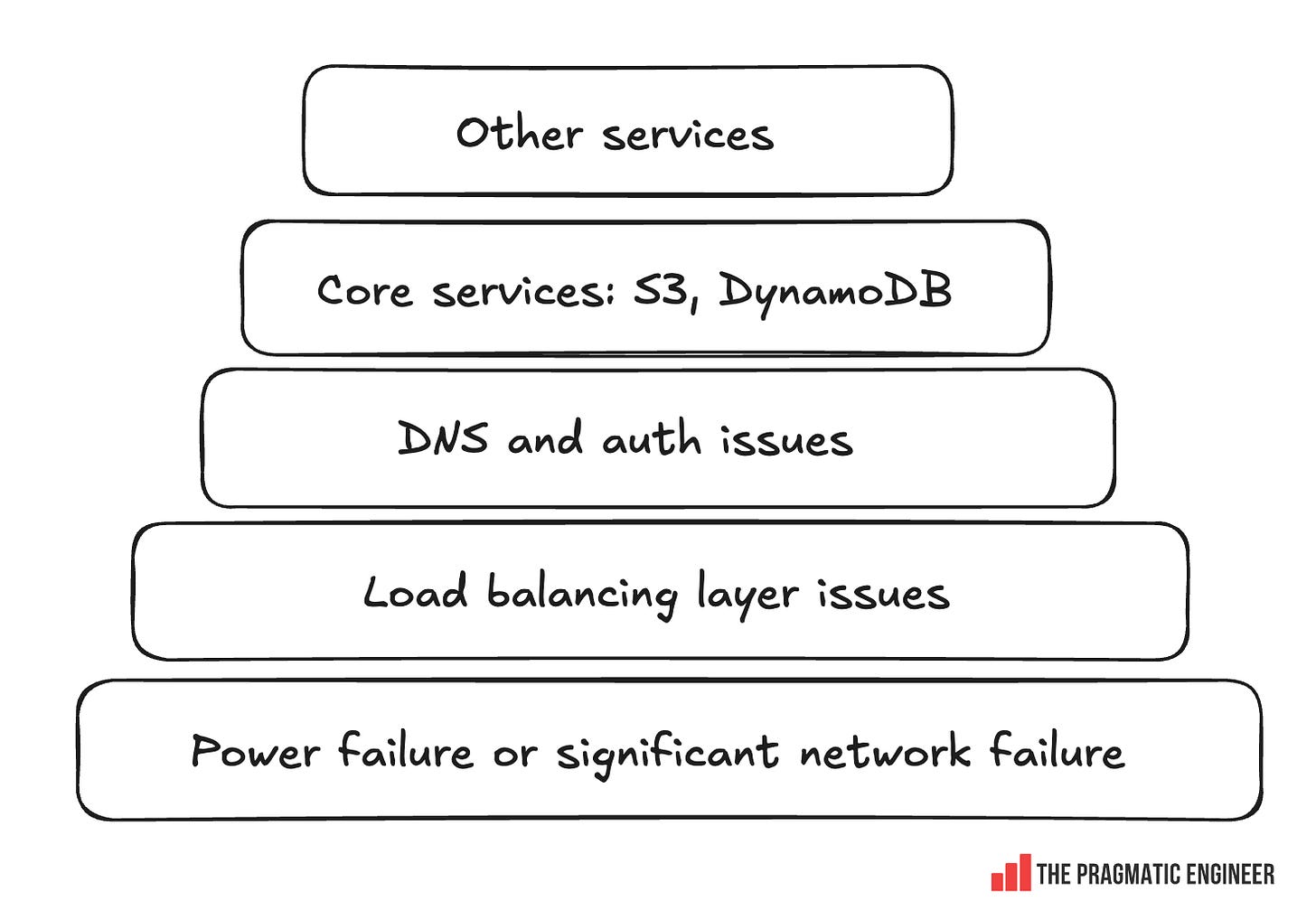

Triage starts immediately. At this point, 100+ services were showing problems within us-east-1 due to the broad nature of the outage. From experience, the Incident Response Team has learned that it pays to start systematically debugging common layers of the stack. For such a broad outage, it’s usually a core building block with an issue.

Below is a rough checklist of what the team works through:

The Incident Response team begins by going through a checklist in roughly this order:

Investigate whether there are power failures or significant network failures

Check if the software-defined network and load balancing layers are healthy

Look for issues within DNS and authentication/ authorization services

Confirm that core services are healthy which most AWS products build on; like KMS, DynamoDB and S3

Two problems at once

As the team went through the list, two coincidental issues were uncovered within a minute of each other.

Sunday, 19 Oct, 11:48 PM: a networking failure event starts. Network packet loss is detected in the “border” network which connects the us-east-1-az1 availability zone to the wider AWS backbone and internet. A Network Border Group is a unique group from which AWS advertises public IP addresses.

11:48 PM: DynamoDB degradation starts. As packet loss is being detected, DynamoDB also starts to degrade.

11:52 PM: AWS Incident Response automatically detects an impact upon services in us-east-1, and pages the incident response oncall network engineers, and affected service oncalls.

11:54 PM: Automated Triage suggests Networking. Incident response’s automated metric triage system completes, noting a) a change in network performance (increase in packet loss) correlated with the time of the event start, and b) that DynamoDB’s metrics have changed at the same time. Typically, this would suggest a network issue is the cause of the DynamoDB issue.

Monday, 20 Oct, 00:08 AM: after failover to a secondary conference system (more later), there’s an investigation into the networking event. As the network event is “lower in the stack” and initially appears to explain the impact on other services (including DynamoDB), the team focuses on fixing the networking issue.

00:26 AM: Red herring. While the Incident Response team is busy resolving the networking failure in the AZ, someone posts in the incident Slack channel:

“Hang on, why is DynamoDB not resolving in DNS, packet loss would not cause that?”

This is when the Incident Response team realizes that while the networking event has some impact, something bigger is also happening that’s not caused by the outage. Whatever it is, it’s impacting DynamoDB.

This smaller network outage is lower in the stack and started a few seconds before the first DynamoDB alerts, which led the experienced team off track into mitigating the smaller outage.

20 Oct, 00:27am: the call is divided. The DynamoDB investigation is split into its own call, so two technical calls run in parallel:

DynamoDB outage: the focus of the dedicated call

Networking outage: resolving the “smaller” outage continues

Resolving the DynamoDB outage

To bring more senior leaders into the call, Gavin messages three longtime DynamoDB frontend engineers, and asks Incident Response to page them, too.

00:31am: realization that it’s a DNS issue. Using the ubiquitous “dig” tool, the team sees that something is wrong with DynamoDB’s DNS records.

00:35-00:50am: engineers who designed and authored the DNS Enactor service join. The root cause of the issue with DynamoDB ended up being identified as a race condition within a DNS Enactor service, as previously covered.

The quorum (collective) of seven DynamoDB engineers includes folks who built and authored a good part of the DNS Enactor and related services, and who have a combined Amazon tenure of over 50 years. With domain experts on the call, the incident responders let them figure out what has gone wrong with DNS Enactors, while looking for ways to mitigate faster.

As the team will later learn, the cause of the event is an edge case bug in how the three Enactors interact, as covered below.

Hitting the “automation paradox.” The DynamoDB team has built a system with DNS Enactors that automatically does a lot of complicated work to keep their DNS updated. But now that it’s gone wrong, it’s time to manually fix the DNS records.

Here’s where the automation paradox kicked in: the team had never had to manually overwrite the DNS zone files before, as they had a system that could reliably do this! So, it took some time to package up and deploy the change to DNS records via manual intervention.

01:03 AM: a parallel mitigation, before the “full fix.” The problem is that the DNS records for DynamoDB are empty due to the race condition. The first order of business is to restore something that works and relieves customers – even before understanding exactly how things went wrong.

The incident response team prepares a “quick” partial mitigation: within the internal private network, call us-east-1 “Prod” (yes, this really is the name!) and apply an Response Policy Zone (RPZ) override on the DNS resolvers to force the DynamoDB IPs into place, for only this internal network. As it hosts many AWS services, this will help restore services like Identity and Access Management (IAM) and Secure Token Service (STS).

01:15 AM: mitigation. The incident team performs an override to force DynamoDB IPs into the us-east-1 Prod DNS on DynamoDB’s most common domain name. Then, the incident team performs a second override of DynamoDB IPs on DynamoDB’s other domain names. At this point, services like IAM, STS, and SQS in us-east-1 recover.

02:15 AM: fix for public DynamoDB DNS found and applied. The team figures out how to fix the public DNS records for DynamoDB, and applies this to restore DynamoDB for all customers.

The engineers look through the zone and realize the top-level alias record for the DynamoDB domain is pointing at a non-existent tree of records (the old “plan” was deleted). They also note that a set of backup trees which the system maintains are still present. As a result, their task is to stop the automation system to prevent it from interfering, delete the broken alias record, and create a replacement that points at the rollback tree.

02:25 AM: DynamoDB recovered. The first part of the incident is resolved. However, Amazon EC2 continues to have issues, and Network Load Balancer (NLB) would have problems later that night.

3. What actually caused the outage?

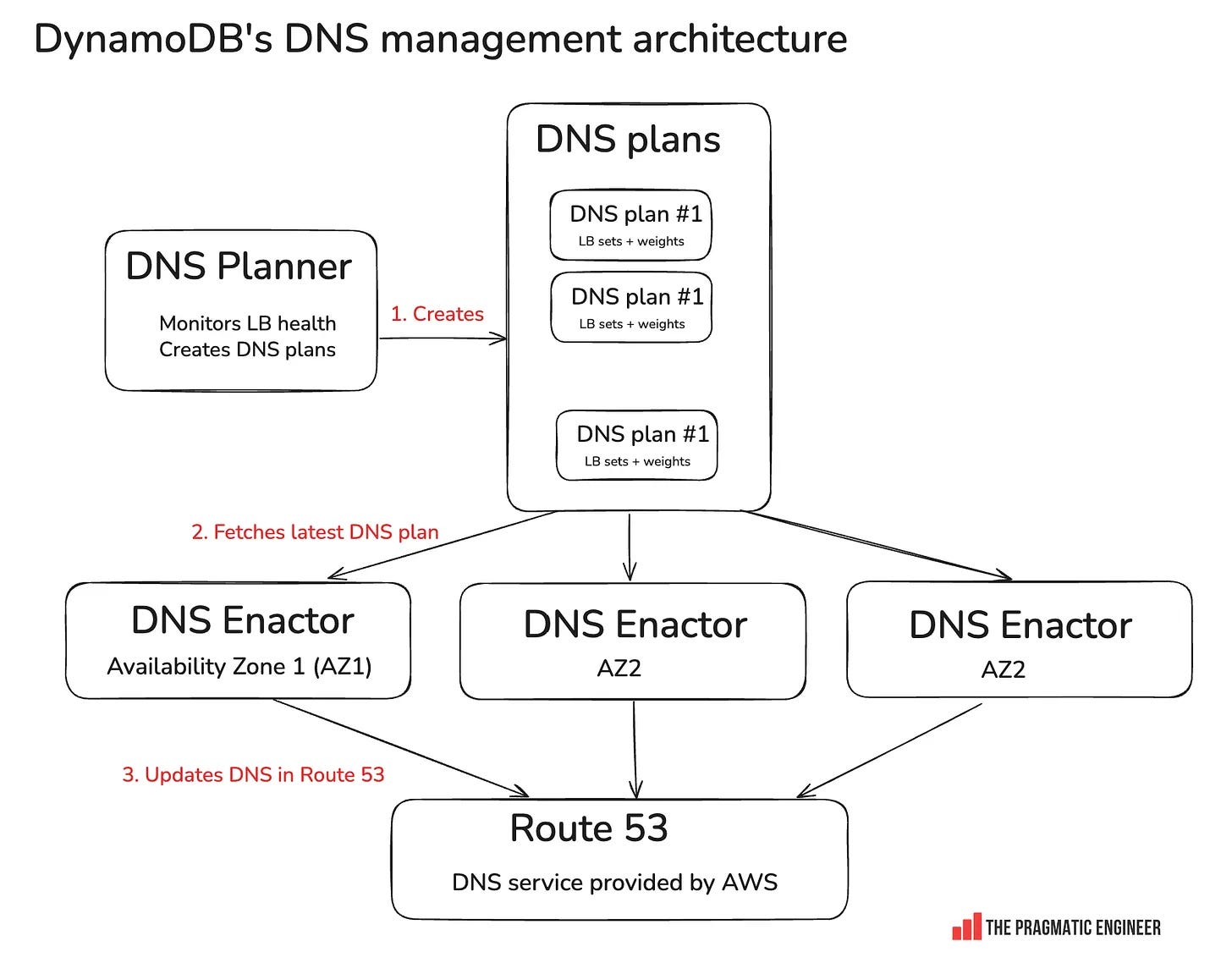

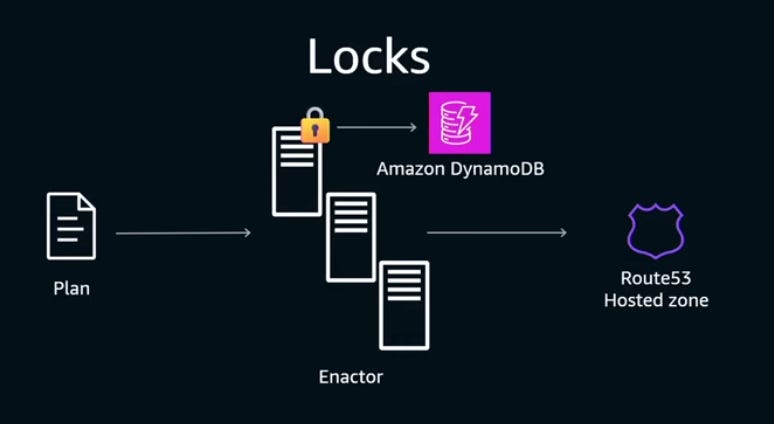

AWS runs three independent DNS Enactors, and each takes DNS plans and updates Route 53. DNS Enactors are eventually consistent: meaning that the DNS plans in any single Enactor will eventually be consistent with the source of truth. This is unlike strongly consistent systems where you can be certain that after writing something, the whole system is consistent.

Using an optimistic locking mechanism is a common solution to prevent multiple writers from changing the same record. The AWS team wanted to achieve this: have only one Enactor writing to Route 53 at any single given time.

You need to have some kind of key-value database to implement optimistic locking. For example, you could use DynamoDB for this:

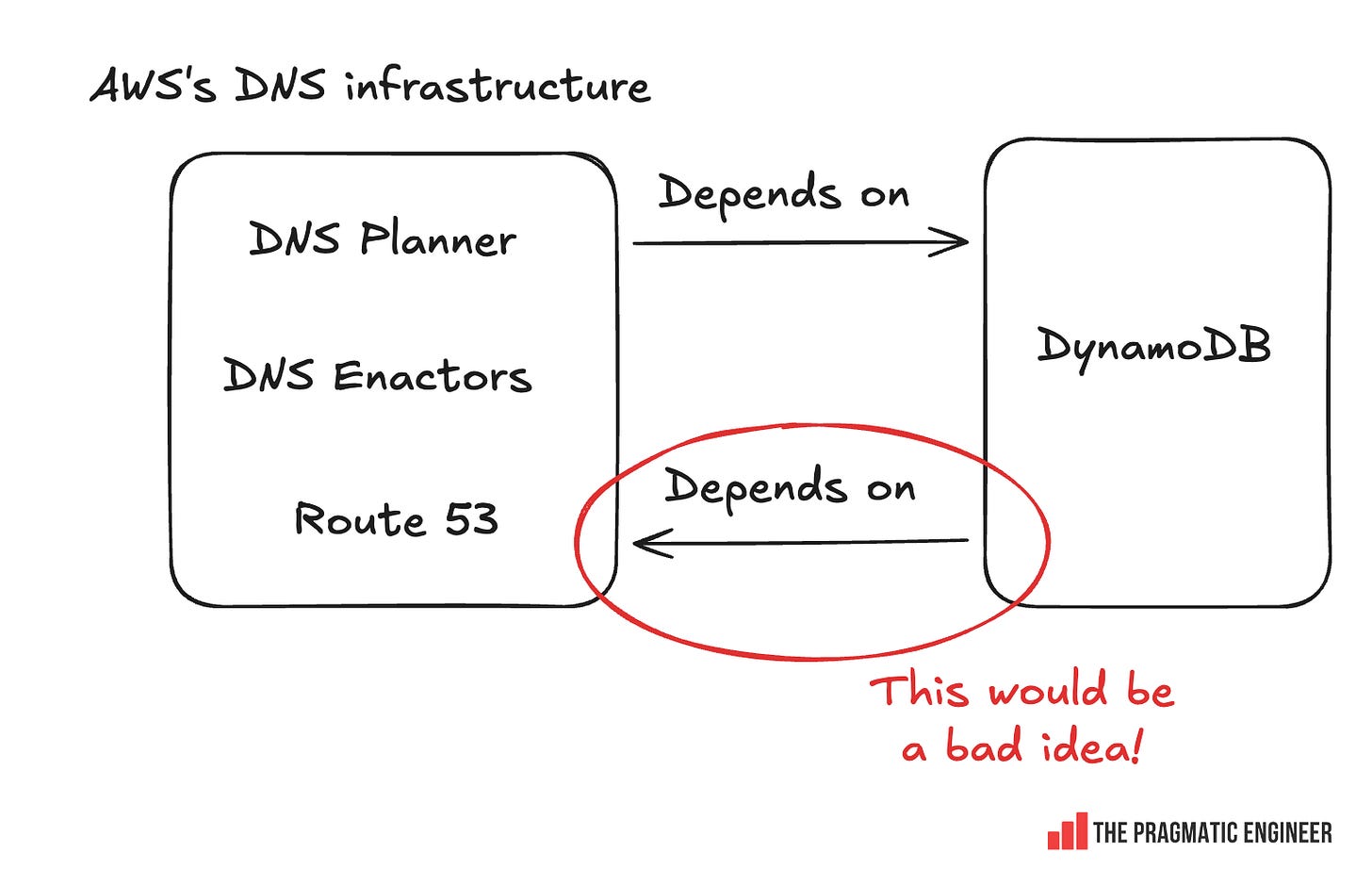

The problem with this approach would have been that DynamoDB itself depends on DNS Enactors, so this would create a circular dependency:

Instead, the AWS team solved the locking problem in a clever way by using Route 53 as the database for optimistic locking. As Senior Principal Engineer Craig Howard explains:

“We didn’t want to add any other dependencies [to DNS Enactors]. Right now, all we depend on is the DNS Plan, and Route 53 (Amazon’s DNS service.) Can we use Route 53 to create a lock? Well, you can!

You create a TXT record, and the existence of that TXT record indicates who the holder of the lock is. The value of the text record is the host name of the lock holder, and then you put the epoch [length of time] in seconds for how long this lock is alive for.”

The AWS team used the transactional characteristic of Route 53: the Route 53 control plane ensures that “CREATE” and “DELETE” operations for TXT are transactional – they either succeed or fail.

So, this is how a lock is created:

CREATE “lock.example.com” TXT “<hostname> <epoch>”

As lock creation is transactional, whenever a DNS Enactor wants to create a new lock for its own use, it first deletes the old lock because it can be certain that lock creation /deletion is transactional. Then it creates the new lock:

DELETE “lock.example.com” TXT “<hostname> <old epoch>”

CREATE “lock.example.com” TXT “<hostname> <new epoch>”

// Insert updated Route 53 DNS records

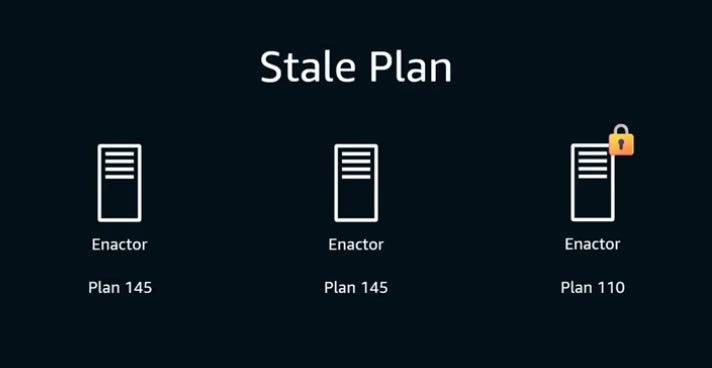

Lock contention is what started the outage. In this case, one Enactor was very unlucky and failed to gain a lock several times in succession. At that point, the plan it is trying to install is older than anyone had ever envisioned. By the time this “unlucky” Enactor gains the lock, an up-to-date Enactor takes over and its “record clean-up” workflow detects a very old plan and deletes it. This was an older plan than the team expected.

Craig explains how this strange race condition played out in this re:Invent talk, shared earlier this week.

What started the outage? As the team will later learn, the cause of the event is an edge case bug in how the three Enactors interact. They are designed to operate independently for resilience, with each Enactor optimistically taking a lock on the DNS zone, making their changes, and releasing the lock. If an Enactor fails to obtain a lock, it backs off and then tries again later.

4. Oncall tooling & outage coordination at Amazon

Let’s hit pause on the incident mitigation to look into some unique parts of Amazon’s oncall process.