How Codex is built

A deepdive into how OpenAI's Codex team builds its coding agent, how engineers use it, and what it could mean for the future of software engineering. Exclusive

More than a million developers use OpenAI’s multi-agent coding assistant every week. Named Codex, usage has increased 5x since the start of January, the team tells me. In the first week of February, OpenAI launched the Codex desktop app, a macOS application that CEO Sam Altman calls “the most loved internal product we’ve ever had”. A few days later, OpenAI shipped GPT-5.3-Codex, which they describe as the first model that helped create itself.

Personally, I’ve been warming up to Codex since doing an interview for The Pragmatic Engineer podcast with Peter Steinberger, the creator of OpenClaw, in which he revealed that he writes all of OpenClaw with Codex, preferring longer-running agentic loops. Update: on Monday, Peter announced he is joining OpenAI to work on building next-generation agents. It’s a major win for OpenAI and the Codex team, while OpenClaw remains independent and open source. Check out my podcast with Peter in his first in-depth interview, around when OpenClaw (back then: Clawd) was getting massive momentum.

To find out how Codex was built, how teams at OpenAI use it, and what effect it’s having on software engineering practices at the ChatGPT maker, I spoke with three people at OpenAI:

Thibault Sottiaux (Tibo), head of Codex.

Shao-Qian (SQ) Mah, researcher on the Codex team who trains the models that power it.

Emma Tang, head of data infrastructure, who isn’t on the Codex team but whose team uses Codex heavily.

This deep dive covers:

How it started. From an internal experiment in late 2024, to a product used by more than a million devs.

Technology and architecture choices. Why Rust and open source? In-depth on how the agent loop works.

How Codex builds itself. Codex itself writes more than 90% of the app’s code, the team estimates. Also: interesting engineering practices like tiered code review, Codex self-testing itself, and onboarding new engineers to the team via pairing.

Research. Training the next Codex model with the current one has parallels with software engineering. Running evals, A/B testing and internal dogfooding.

Codex usage at OpenAI. Emma’s data team built an internal “data agent” in two months — that would have probably taken over a year, before. The number of PRs is so large that the traditional PR flow is starting to crack, though.

How software engineering is changing at OpenAI. The “30/70 rule:,” some engineers returning to tab-complete, and the importance of “taste.”

Next steps. GPT-5.2 step change, the capability overhang, and where Codex goes next.

Last week’s debut Pragmatic Summit, in San Francisco, featured a fireside chat with Tibo, myself, and the audience, and featured new details about how Codex is built. Paid subscribers can watch this recording now. Free subscribers will get access to all videos from the Pragmatic Summit in a couple of weeks.

Longtime readers might recall a deepdive entitled How Claude Code is built, based on interviews with the founding engineers at Claude Code. Some comparisons with today’s topic are obvious: Codex and Claude Code have each made bets that seem to be paying off. I was initially skeptical when I talked with the Codex team last October because the cloud-first, long-running task approach didn’t click with me. But I’ve now changed my mind.

1. How it started

In 2024, OpenAI was experimenting with various approaches for building a software agent. That fall, the company declared that building an aSWE (Autonomous Software Engineer) was to be a top-line goal for 2025. This vision came from the top: Greg Brockman and Sam Altman believed they should have an autonomous software engineer working alongside teams. Tibo describes the thinking:

“Greg and Sam had the strong conviction: ‘eventually, we should have an autonomous software engineer working alongside us and with the capabilities seen from o1-preview, the time is now to have a group absolutely dedicated to making this a reality’”.

A number of folks who’d worked on earlier prototypes were pulled into the effort, which featured:

Michael Bolin: tech lead for the Codex open source repository.

Gabriel Peal: who subsequently built the VS Code extension, mostly solo, and built the foundations of the Codex desktop app.

Fouad Matin: who led the initial release of the Codex CLI, and is responsible for Codex’s safety and security approach.

OpenAI had two teams tackle different segments of the problem space: Codex Web would focus on an async, cloud-based solution, while Codex CLI targeted iterative, local development. Both products would launch in the spring, with Codex CLI being announced in April 2025, and Codex in ChatGPT introduced in May.

2. Technology and architecture choices

An obvious difference between Codex and Claude Code is the programming language. Claude Code is written in TypeScript, “on distribution”, which plays to the underlying model’s strengths. Meanwhile, the Codex CLI is written in Rust. Tibo explains why:

“We debated TypeScript, Go, and Rust. All three seemed like solid contenders for different time horizons. In the end, our reasoning came down to a few layers:

Performance: We want to eventually run this agent at a massive scale where every millisecond matters. Performance is also important when running locally in a sandboxed environment.

Correctness: We wanted to choose a language that helps eliminate a class of errors with things like strong typing and memory management.

Engineering culture and engineering quality: There’s this interesting thing that language choice does: it gets you to think about the engineering bar you set. We decided to pick Rust because it’s extremely important for our core agent implementation to be extremely high quality”.

There was also a practical concern about dependencies. Choosing TypeScript means using the npm package manager. Using npm often means building on top of packages that may not be fully understood – which could clearly be problematic. By going with Rust, the team has very few dependencies and can thoroughly look through the few dependencies there are.

They also want to eventually run the Codex agent in all sorts of environments – not just laptops and data centers – and even places like embedded systems. Rust makes this more achievable from a performance perspective than TypeScript or Go.

Tibo tells me that while Codex’s early performance was less standout with Rust than with TypeScript, they expected the model to catch up. Plus, choosing Rust gave them one more engineering challenge to work with. The Codex team also hired the maintainer of Ratatui – the Rust library for building terminal user interfaces (TUIs). He’s now full-time on the Codex team, doing open source work.

The core agent and CLI are fully open source on GitHub.

How Codex works

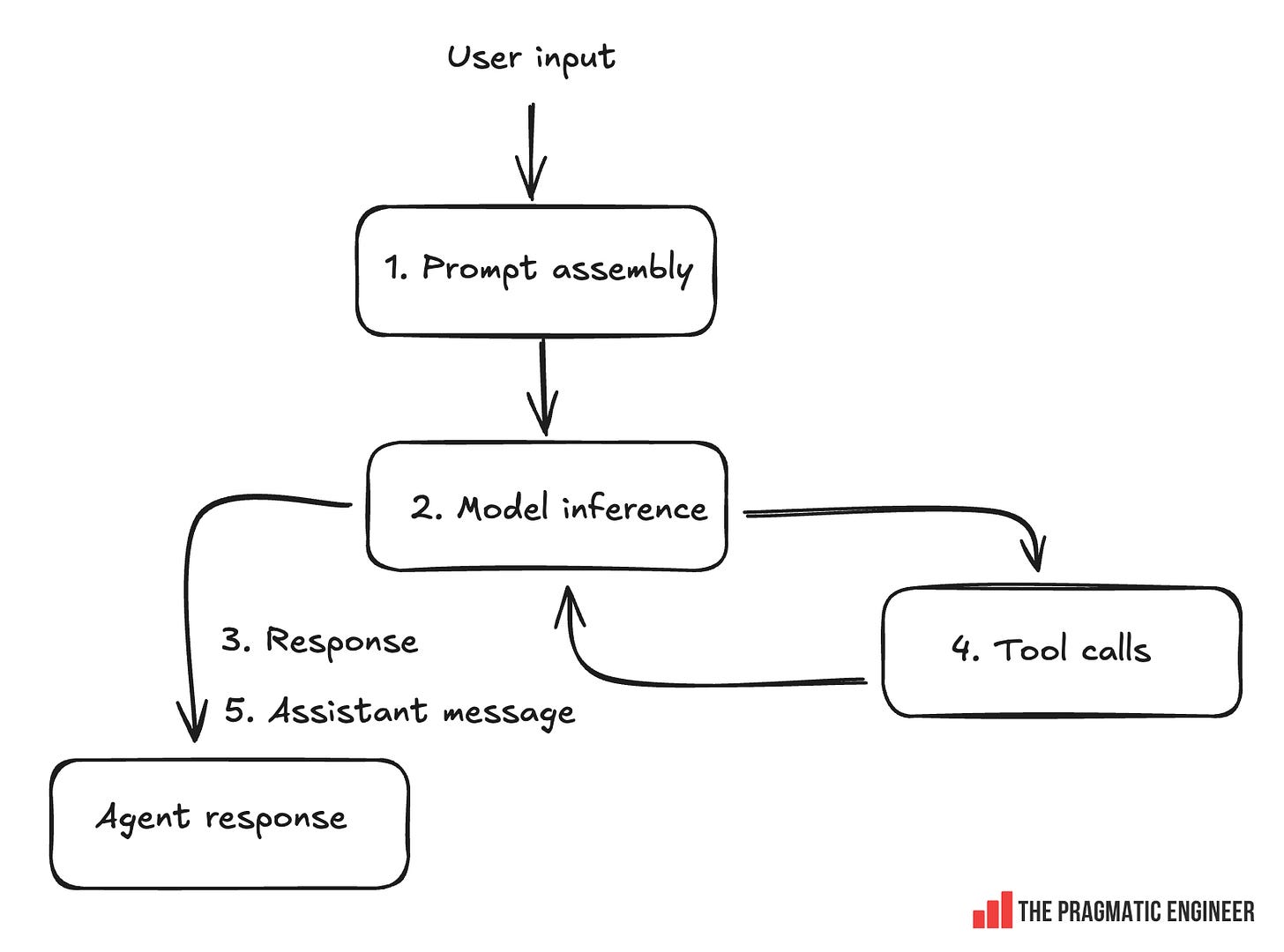

The core loop is a state machine, and the agent loop is the core logic in the Codex CLI. This loop orchestrates the interaction between the user, the model, and the tools the model uses. This “agent loop” is something every AI agent uses, not just Codex, and below is how Codex implements it, at a high level:

Prompt assembly: the agent takes user input and prepares the prompt to pass to the model. On top of user input, the prompt includes system instructions (coding standards, rules), a list of available tools (including MCP servers), and the actual input: text, images, files, AGENTS.md contents, and local environment info.

Inference: the prompt is converted to tokens and fed to the model, which streams back output events: reasoning steps, tool calls, or a response.

Response:

Stream the response to the user by showing it on the terminal.

If the model decides to use a tool, make this tool call: e.g. read a file, run a bash command, write code. If a command fails, the error message goes back to the model, the model attempts to diagnose the issue, and may decide to retry.

Tool response (optional): if a tool was invoked, return the response to the model. Repeat steps 3 and 4 for as long as more tool calls are needed.

Assistant message: the “final message” intended for the user which closes one step in the loop. The loop then starts again with a new user message.

Compaction is an important technique for efficiently running agents. As conversations grow lengthy, the context window fills up. Codex uses a compaction strategy: once the conversation exceeds a certain token count, it calls a special Responses API endpoint, which generates a smaller representation of the conversation history. This smaller version replaces the old input and avoids quadratic inference costs. We covered how self-attention scales quadratically in our 2024 ChatGPT deepdive.

Safety is an important consideration because LLMs are nondeterministic. Codex runs in a sandbox environment that restricts network access and filesystem access by default. Tibo reflects on this choice:

“We take a stance with the sandboxing that hurts us in terms of general adoption. However, we do not want to promote something that could be unsafe by default. As a dev, you can always go into your configuration and disable these settings if you want.

We made this default setting because many of our users are not that technical. We don’t want to give them something that could have unintended consequences”.

There are several releases per week. Internally, the team ships a new version of Codex up to three or four times a day. Externally, new releases are cut every few days and are distributed via package managers, Homebrew, and npm.

Michael Bolin’s recent blog post, “Unrolling the Codex Agent Loop,” lays out the internals of how the agent loop works.

3. How Codex builds itself

More than ninety percent of the Codex app’s code was generated by Codex itself, the team estimates, which happens to be roughly in line with what Anthropic has reported for Claude Code, according to what its creator Boris Cherny told me. Both AI labs share the meta-circularity of using the coding tools to write their own code.

Tibo tells me that a typical engineer on the Codex team runs between four and eight parallel agents, which do any one of a number of tasks:

Feature implementation

Code review

Security review

Codebase understanding

Going through plans and summarizing

Going through what team members have done and summarizing changes

Bugfixes

… and more.

Codex engineers are now “agent managers” and no longer just write code. Tibo says it’s common for an engineer to walk into the office with several tabs open on their laptop: a code review running in one, a feature being implemented in another, a security audit in a third, and a codebase summary being generated in a different tab. He says:

“Codex is really built for multitasking. There’s this understanding that most tasks will just get done to completion.

People on our team have figured out what Codex is and isn’t capable of. There is a tricky thing in all of this, though: we have to relearn these capabilities with every model”.

Frequently-used “skills”

“Agent Skills” are ways to extend Codex with task-specific capabilities, which is pretty much the same concept as Claude Code’s skills. Internally, the Codex team built 100+ Skills to share and choose from. Three interesting examples:

Security best-practices skill: a comprehensive write-up of all security practices adopted by the team. When invoked, Codex goes through each practice, checks the code, and generates patches for anything missing.

“Yeet” skill: takes any code change, writes up the PR title and description based on the original plan, and creates a draft PR in one step.

Datadog integration skill: Codex connects to Datadog, reviews alerts and issues, finds problems, and tries to generate a fix for them.

The way Tibo thinks about skills is that they help steer the model to more specific behaviors, and they can also be combined. Skills are continuously published internally and team members copy from each other.

Tiered code review

The team set up AI code review and it always runs. The team trained a bespoke model for code review, optimizing it for signal over noise. Around nine out of 10 comments point out valid issues, says Tibo, which is equal to or slightly better than human reviewers. AI reviews are run automatically whenever a pull request moves from “draft” state to “in-review” state, and are automated via a GitHub webhook.

Following an AI review, there are two possible next steps:

Non-critical code: can be merged with no further human review. For non-critical parts of the code where speed matters more than perfection, the engineer running the agent can decide to merge the code following an AI review, when they decide it’s ready.

Key parts of the codebase: mandatory human review. For key code parts such as the core agent and open source components, the team insists on careful human code reviews.

Other engineering practices on the team

Here are more practices that Tibo rates as helpful for the Codex team:

AGENTS.md. Instructions stored inside a repository. On the Codex team, these files tell the agent how to navigate the codebase, which commands to run for testing, and how to follow the project’s standards. These are a bit like README files, but written for AI agents instead of humans. Agents.md has become a de facto standard across agents, and the only major agent not to use it is Claude Code. See agents.md for more details.

Structure code for agents: have tests! The team has deliberately structured their codebase “to make it inevitable for the model to succeed”. Structuring means having tests in-place, clear module boundaries, and instructions on how the model should run validation (eg: tests, linting, etc). When the model implements something incorrectly, a test fails, the agent notices, and it tries to figure out what went wrong. Since the model is trained to be persistent, it keeps trying until it gets it right. Tasks can run for 20 to 30 minutes, or sometimes an hour.

Codex running the test suite to test itself. In what is an interesting meta-testing capability, Codex can fully test itself, using a specific skill. This skill runs tests for all of Codex’s own features. Amusingly, Codex seems to invoke this skill more often than expected.

Overnight, Codex runs to generate suggested fixes. The team set up nightly runs of Codex, instructed to look for issues across Codex. Every morning, engineers review issues that Codex identified with the codebase, with fixes waiting for review.

Onboarding to the Codex team via pairing. New joiners are asked to keep an open mind about how the Codex team does development, and are warned that the “how” of building software is different than at most places. A new joiner is paired with an engineer on the team and shadows them for the first part of the day, observing how they develop with Codex. They are then assigned a task in the second half of the day, and are expected to ship it to production on the same day.

Unlimited Codex usage. To put everything in this deepdive in context, OpenAI employees – just like at Anthropic – have no usage cap on LLMs. This makes sense given they are building a tool they want customers to use as much as possible. However, it’s in contrast to non-AI labs. Keep this in mind as we go through how the team operates.

Using Codex to debug Codex

The Codex team holds meetings to discuss Codex, during which it’s common for engineers to fire off a thread within Codex to see if it can come back with some information. This January, something interesting began happening, Tibo told me:

“When we asked questions related to why Codex runs in a certain way, Codex decided to debug its own systems. It connected to logs, SSH’d into research dev boxes, and analyzed ML instabilities.

It figured out a lot of useful information, and wrote a little report we could present on the screen. So, we ended up going through this doc in the meeting”.

This feels like another meta-circularity of Codex debugging itself – or at least systems that power it!

4. Research

Codex is built by researchers as well as software engineers, of whom one is SQ Mah. He managed to move into research from software engineering by competing in the Vesuvius Challenge, of reading millennia-old carbonized scrolls from the ancient Roman town of Pompeii which were buried by a cataclysmic volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. SQ finished second in the contest by renting GPUs on Google Cloud, training models, taking research ideas and turning them into useful algorithms.

So, what is “research” like at OpenAI? SQ’s take: