How to become a more effective engineer

The importance of soft skills, implicit hierarchies, getting to “small wins”, understanding promotion processes and more. A guest post from software engineer Cindy Sridharan.

Hi – this is Gergely with the monthly, free issue of the Pragmatic Engineer. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. To get weekly emails like this in your inbox, subscribe here:

This article is a guest post. Interested in potentially writing one in The Pragmatic Engineer? Details on expressing interest.

Today happens to be election day in the US: the biggest political event in four years. While we will not discuss that kind of politics in this publication: this event is a good excuse to discuss the other type of politics: workplace politics. Specifically: for software engineers and engineering leaders.

Cindy Sridharan is a software engineer working in the Bay Area. I originally connected with Cindy years back, online, over distributed systems discussions, and we met in-person last year in San Francisco. As the topic of internal politics for software engineers came up, Cindy, frustrated with the kind of careless, non-productive discourse that swirled around this topic, wrote an article about it, back in 2022.

The article really resonated with me – and with other people I shared it with. So with the permission and help of Cindy, this is an edited and updated version of Cindy’s original article.

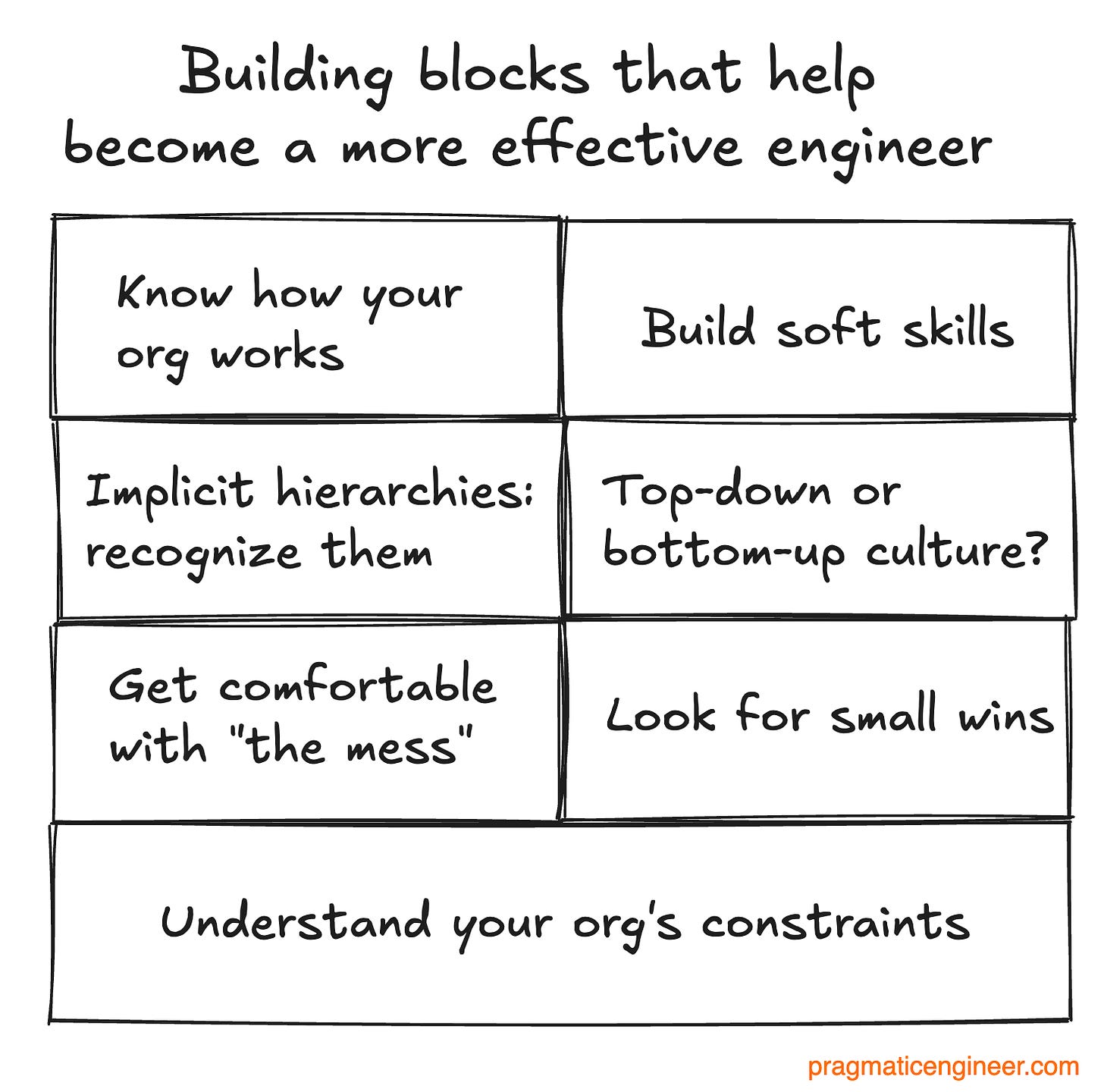

In this issue, Cindy covers:

Know how your org works

Soft skills: these are hard skills!

Implicit hierarchies

Cultures: top-down, bottom-up, and both at the same time

Get comfortable with the “mess”

Look for small wins

Understand organizational constraints

As related reading, see these The Pragmatic Engineer Deepdives:

Internal politics for software engineers and managers: Part 1

Internal politics for software engineers and managers: Part 2

With this, it’s over to Cindy:

Some time ago, exhausted by never-ending complaints about self-defeating reward structures at companies, I made what seemed to me a fairly self-evident comment:

Some of the responses this comment garnered were, well, rather pointed. Most people’s dismay seemed to have stemmed from what they’d perceived to be my dismissiveness towards their well-intentioned albeit ultimately not very fruitful efforts to make things better at their workplace.

I’ve been meaning to expand on some of my thoughts on this topic for months, since I feel this warrants a more nuanced and considered discussion than is feasible on social media.

This post aims to lay out some problems engineers might often encounter when trying to address causes of dysfunction at their companies. It offers some food for thought on how to be more effective working within the limitations and constraints of organizations.

One caveat I need to mention is that most of what I describe here is from the perspective of an individual contributor (IC). I’ve never been a manager and have no experience of navigating organizational politics as a manager. There are innumerable resources by seasoned managers on how to maneuver managerial politics, for those interested.

Preface: The distant mirage of aspirational ideas

It’s something of a rule of thumb that on social media, topics that generally require careful consideration are painted with reductionist, impractical, or aspirational brushstrokes. This is often done by people with very high levels of visibility, and sometimes by people who really ought to know better. Much of this oversimplified and irresponsible discourse gets excessively amplified, to the degree that it can very quickly become what’s perceived as “conventional wisdom”. None of this is productive. Worse, it gives easily influenced people the wrong idea of how organizations “must” function.

It can be quite discouraging to see aspirational goals get elevated to such heights that anything that falls short of their high standards is often deemed as “toxic” or “dysfunctional.”

Technical debt is a common talking point, so let’s take this as a concrete example. The accumulation of technical debt as teams prioritize building new features at a rapid pace, even if it comes at the expense of quality, performance, testing and so forth: this is a very common occurrence. As an industry, we’ve not built the tools, framework, or even an effective vocabulary required to talk about these tradeoffs, beyond simply calling it “technical debt”. As a result, most conversations around technical debt end up being oddly confusing. People are often disappointed about how “leadership doesn’t get tech debt” or about how features are always prioritized over critical maintenance work.

Yes, ideally we should have a culture which prioritizes minimizing technical debt and building software sustainably, not just shipping features. But you’d be hard-pressed to find a single team or organization that prioritizes addressing technical debt as the primary focus of the team for a longer period of time. If and when technical debt does get prioritized as the primary focus of the team, it’s often because the technical debt has a noticeable and negative impact on a key, well-tracked, highly visible metric that reflects poorly on the team.

If your team is hitting all deliverables on time, then there might be an appetite for addressing the issue of technical debt in fits and starts. But in the vast majority of cases, addressing technical debt needs to be undertaken iteratively. You need to initially aim for small and easy wins that inspire confidence and lay the groundwork for you to push for bigger and better improvements. And you need to do all of this without slowing down your team’s delivery pace. Preferably without having protracted conversations with “leadership” to get necessary buy-in to do so.

Social media, blog posts and conferences amplify aspirational ideas (if leadership just “gets” why technical debt is so harmful and “prioritizes” it, then we can easily address this problem). Your organization, however, rewards what you actually get done which benefits the organization. This might be a very far cry from whatever might be de rigueur on social media.

1. Know how your org works

One of the most effective things you can do to be successful at your job is to understand how your organization works. This understanding will better inform your outlook on all things, including:

exactly what technical skill you need to invest effort into getting better at, which will actually be rewarded

how to build lasting relationships with other people on your team or organization that ultimately dictate the success of a project

how to effectively pitch projects or improvements to leadership and actually see these through to completion

how to navigate ambiguity

how to manage conflicting priorities or expectations

how to best deal with setbacks

how to weigh the pros and cons of technical choices in the larger context of the organizational realities and needs

how to identify and drive quick wins

how to discern what’s achievable, and in precisely what time frame

how to use this knowledge to judiciously pick battles

and in the worst case, to know when to cut your losses and quit

Managers need to deal with these skills as a part of their job description and so do ICs at the very senior levels. But it’s never too early in your career to start cultivating this knowledge. In fact, a core part of mentoring engineers involves educating them in how the organization works, to enable them to build a successful track record of getting things done.

Some managers and senior ICs often take a short-sighted view and see “shielding” non-senior folks from organizational politics as a way to help other engineers “maintain focus.”

Shielding non-senior engineers from organizational politics not just stymies their growth, but also hinders their visibility of the skills they’ll eventually need to learn the hard way. These are the kind of skills for which there exists no easy playbook.

2. Soft skills: these are hard skills!

This post doesn’t aim to be a comprehensive guide on how to learn the skills which helps one truly understand how an organization works, or even a comprehensive list of the skills themselves. Some of the points mentioned in this article that help one better understand how an organization works are simply ones I’ve encountered. If you ask someone else in a different organization, you might get a very different list. It’s no exploit to learn a new skill when you know exactly what to learn, how to learn it, and so long as the answer is straightforward, as is the case with many purely technical concepts.

Learning “how your organization works” is a constant exercise in learning the organization’s ever-changing landscape, especially as people, projects, priorities, partners, and leadership change. Learning how to make decisions when key pieces of information are missing is also a very important skill, insomuch as it helps you hone another set of valuable skills:

how best to gather information you’re missing

how and when to get by without doing so

Some of these skills I’m talking about can be learned by talking to people and some need to be inferred through close observation of leadership’s decisions. There are some skills, however, that can only be learned the hard way by getting things wrong, or watching other people get things wrong.

In organizations with a culture of constant learning, visibility into failures isn’t something that’s discouraged. At the same time, whether your organization is one such which subscribes to the school of thought of making failures visible: this is something you’d only learn if you know how your organization works.

The most important skill for any engineer to possess is the ability to learn quickly. This applies to both technical concepts and sociotechnical concepts. I’m absolutely by no means an expert in any of these myself; but over the years, I like to think I’ve got a better understanding of why this knowledge is important.

3. Implicit hierarchies

Most organizations have a formal structure. They usually start with a VP or a Director at the top, and proceed down to individual teams. If you’re an IC, you’re a leaf node in the org tree.

Most organizations, in my experience, also tend to have something of an informal structure, especially among ICs. In organizations that make job titles and levels public, it’s relatively easy to know which engineer might have more influence. In organizations where this is concealed, it’s a lot harder to infer the informal hierarchy, and where exactly you fit into it. Sometimes, it’s not so much to do with job titles and levels, than with tenure on the team or the organization. And sometimes, it’s some other factor, like subject matter expertise, open-source experience, or even something as arbitrary as employment history.

It’s important to be aware of this informal hierarchy because as often as not, it may directly influence your work, irrespective of your personal level and job title.

Engineers who wield an outsized influence on the decision making process tend to often be fairly senior, and also fairly opinionated. It usually isn’t even any particular opinion they might have on any topic that drives their decision making: but it’s usually overarching philosophies which guide their thinking.

These opinions could shape everything from:

the way your codebase is structured

to the tooling in use

to the way the team tests or deploys a system

to the way the system is architected

to the reason why the team did or didn’t choose a specific technology to work with, or a specific team to partner with

to the reason why some things that seem “broken” are never prioritized

and more.

These philosophies and the opinions guided by them can end up being the decisive factor in whether your efforts to make any change or improvements to the existing system will be fruitful or not. Unless you understand “why” things are the way they are – for there often is a method to every madness, if you’re patient to dig deep enough – your proposal on “how” to improve the situation may end up going against the grain, making it that much more of an uphill task for your proposal to be accepted.

Furthermore, your well-intentioned proposal to fix something that appears obviously “broken” or “neglected:” doing so runs the risk of making you seem like someone who did not put in effort to understand the history of the system. Being perceived as someone who did not do their homework doesn’t exactly breed confidence in why you should be entrusted with fixing the system!

One of Amazon’s Principle Engineering Tenets is “Respect What Came Before”. Many systems that appear to be “broken” are worthy of respect, and efforts to evolve them must be tackled from multiple angles:

Understand the implicit organizational hierarchy

Identify the people who wield unusually high influence; understand their way of thinking and general philosophies. Do this by either talking to them or other people in the organization, by researching their work, reading any articles or blog posts they wrote, or talks they presented, etc.

Identify how their philosophies were successfully applied to projects and teams they worked on. Why were these efforts considered successful? What were the problems that were solved by these philosophies? What problems were made worse?

How do you build credibility with highly influential people within the organization? Can you lean on your past work? Your subject matter expertise? Your previous track record? Is there someone they trust and respect who can vouch for you, for them to take a leap of faith and agree to do things your way?

These are all things to consider before making proposals to change a system. Smaller changes might not require this level of rigor, and might in fact be a good way to net a lot of easy wins. But for anything more involved and more high impact, learning how and why your organization makes technical decisions is a non-negotiable requirement.

4. Cultures: top-down, bottom-up, and both at the same time

Irrespective of titles and hierarchies, most organizations also have a top-down or bottom-up culture, or a mix of both. In absolute terms, neither one is superior compared to the other. Microsoft is a top-down organization. Meta has a bottom-up culture. Both are extremely successful companies.

In top-down cultures, the most important decisions are made from above. The person making the final decision could be a tech lead, sometimes a manager, or a Director-level executive. On such teams, much of your success boils down to “managing up”. Successfully managing up requires grappling with questions about the decision maker, such as:

Are you on the same wavelength as them? Do you both attach the same salience to the problem at hand? If not, are you up to the task of impressing upon them its importance and urgency?

Is there some information or knowledge they have and you don’t, that informs their thinking on the matter? How best can you get this information?

Do you both share the same view of the opportunity cost?

What are their implicit and explicit biases? What are their blind spots? Can you use some of these to your advantage?

What are the things they generally value? What kind of work or behavior impresses them?

Is there any specific abstraction or process or methodology they are particularly attached to? Can you lean in on these to more effectively market your opinion to them?

What’s the timeline they are comfortable working with to solve the problem? A month? A performance cycle? Many years?

What’s your personal level of trust with them? Will they go to bat for you?

What does “success” mean to them and how do they measure it? How have they typically measured it for in-progress work?

How do they typically handle setbacks? Have you drawn up contingency plans and shared them?

How do they handle failure? Do they assume responsibility for it, or will you be scapegoated – and possibly fired?

Do they have a culture of blameless postmortems for large-scale team or organizational failures? Are these lessons shared and discussed transparently with everyone on the team and in the organization?

What is their experience of working with partner teams or organizations?

Have they been burned badly in the past when working with another organization or another team?

What’s their organizational reputation? Are they well-liked? Respected?

How conflict-averse or otherwise are they?

Knowing the answer to these questions can give you a sense of how best to identify problems and propose solutions, to see them through, and demonstrate a level of impact that might advance your career.

On bottom-up teams, the challenge is to manage laterally while also managing-up. This includes grappling with conundrums like:

How do you build consensus among your peers when there’s no top-down decision-making authority?

How do you break down barriers between peers?

How do conflicts get resolved if there’s no higher authority to mediate? Does it boil down to nitty-gritty quantitative details like metrics, or something more nebulous such as “likeability”?

If all key ideas have to originate from the bottom, which ones make it to the top? How has this worked in the past?

Can coding solve all issues? Can you prototype an idea you have and then successfully pitch it? Does your team or organization empower you to do this during business hours, or are you willing to spend your nights and weekends pursuing this goal?

Did someone already attempt to solve the problem you’re trying to fix? How did that go? What were the failures? Do you understand the proximate cause of any failures? Are you sure you won’t run into the same issues again?

What’s the opportunity cost? Can you convince your peers it’s worth solving right away if it hasn’t been prioritized to date?

What’s your scope of influence? Does it extend to your team, your sister teams, or your entire org? Are people outside your team willing to give your solution a whirl?

How do you convince people or teams with different incentives? Is this something you can even do without top-down support?

How do you ensure adoption, especially cross-organizational adoption?

How do you enlist partners or advocates for your effort? Are there other teams ready to adopt your solution, were you to just build it and advocate for it?

Do you have key relationships with the stakeholders? Do they trust you? If not, why not? And how would you go about building this trust?

How do you convince peers with bad experiences of your team or project in the past?

How do you build credibility?

How do you motivate and incentivize your peers in general?

What’s the cost of failure? Just one fair to middling performance cycle, or something worse? Who’ll be impacted; Just you, or your entire team?

What are the cultural problems? In a bottom-up setting where there’s no higher authority to mandate teams to change how they work, how do culture problems get fixed?

There are many organizations that are top-down in some respects and bottom-up in others. On such teams, you’d need to employ a mix of strategies to successfully thread the needle for many of these issues and chaperone your ideas through to successful execution.

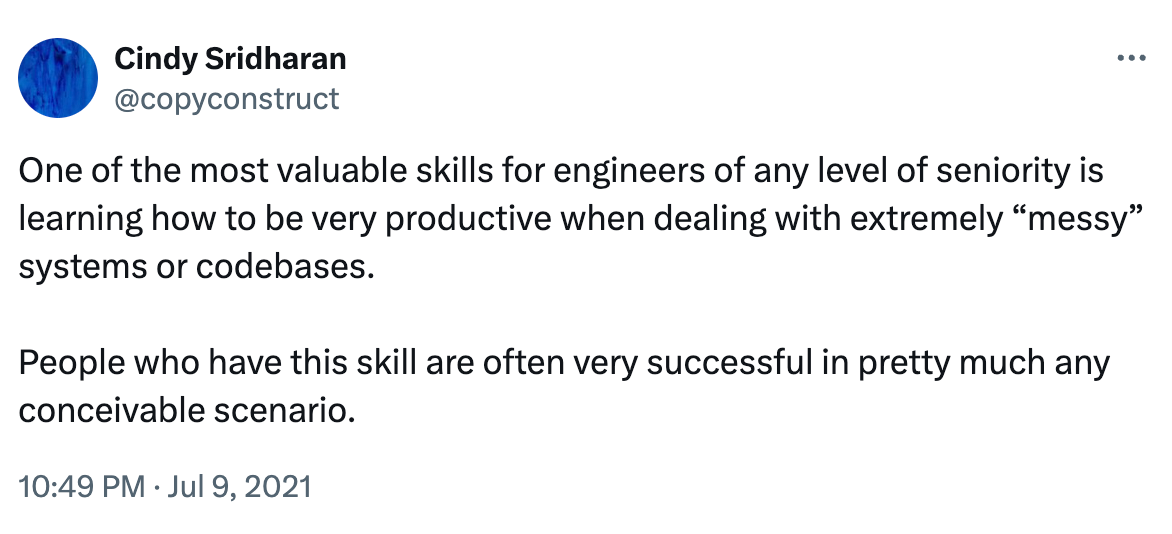

5. Get comfortable with the “mess”

Most organizations value and reward people who “get things done”.

You’re far likelier to encounter codebases that have “evolved” over time, with poor documentation, lots of outdated comments and often with few to no tests, than you are to encounter ones which are perfectly documented, have well-tested public and internal APIs, and code which is perfectly obvious.

You’re going to be far more productive if you learn how to navigate such codebases successfully, which involves learning some of the following:

how to gather just the right amount of information to get on with your task

how not to get too caught up in the weeds, unless required

how to read a lot of code at a fast clip and come away with a reasonably good mental model of what it’s trying to do

how to come up with a hypothesis and to use a variety of general purpose techniques and tools to validate it

how to reproduce bugs quickly without elaborate local configurations and setups

These skills aren’t typically taught in college. They’re seldom talked about on social media or even at conferences. It plays well to the gallery to harp on about the importance of tests or documentation. I’m not trying to minimize their importance. But dealing with mess and ambiguity is a key skill to hone to improve your own productivity when working with code.

The same philosophy applies to working with sociotechnical systems like organizations: get comfortable with mess. You’re far likelier to encounter organizations comprising teams and leaders of:

varying levels of skill and ability to deliver on their promises

varying – sometimes opposing – incentives and reward structures

varying appetites for risk or change

varying philosophical views on software development and systems

varying levels of tolerance for failure

varying willingness to make investments in people and projects with a long-term view

Being successful in “messy” organizations requires quickly learning the topology of the organization and charting pathways to navigate it. Your “personal ideal” may not match the reality on the ground. I’m cynical enough to believe everyone ultimately is looking out for their personal interest, and you need to look out for yours.

Get comfortable with mess and seek out ways to untangle it or work around it. Seek alignment when interests align. Be able to identify quickly when such alignment will always prove elusive. Be quick to dissociate amiably when interests clash irrevocably. Know when to batten down the hatches, but more importantly, also know when to cut your losses. Be transparent.

Treat people with respect and humility, even when they disagree with you, or when you feel they are mistaken. Do this even when they seem to act against the best interests of the team or organization. It might very well be you who is failing to appreciate their predicament and you might be misunderstanding the reason for their actions.

6. Look for small wins

It might take you way longer to truly get the measure of your organization’s sociotechnical politics, than to get up to speed with a codebase.

To build credibility, you need to demonstrate some impact early on, instead of waiting months to get the lie of the land before you start getting anything done. Chasing small wins and low-hanging fruit can be an easy path to productivity. Don’t underestimate their importance.

7. Understand organizational constraints

Individual managers – much less ICs – can sometimes do only so much to solve the more entrenched organizational problems. DEI - Diversity, Equity and Inclusion - is one that quickly comes to mind. I’ve never seen this problem solved in a bottom-up manner successfully, anywhere. The vanishingly few organizations that did make modest progress often enjoyed executive buy-in. Organizations which were serious about DEI had executive compensation tied to the success of DEI efforts.

Just how many organizations still remain committed to the principles of DEI in a post zero interest rates (ZIRP) world is unclear. I do expect this issue to become even more deprioritized in the current environment where companies are laser focused on profitability.

It’s folly for ICs or even managers to wade into fixing this - or any other issue - solo, without explicit approval from their management chain, ideally with this work recognized in performance reviews. It’s one thing to truly feel passionate about a topic and to want to help create change; but please be realistic about expectations and outcomes. Charity Majors wrote a good post titled Know Your “One Job” And Do It First, and I largely agree with everything she says.

This is also applicable to a lot of other issues about “wholesale culture change.” Unless you’ve been hired with the explicit mandate to bring about a change in culture, i.e., at the executive level, you would be well-advised to be extremely wary of embarking on sweeping, ambitious projects or efforts.

That doesn’t mean you can’t create any change at all. The most effective instances of culture change I’ve seen have been incremental. It’s far easier to identify incremental wins when you’ve already learned the ropes by succeeding within the existing, flawed, cultural framework, than by starting from the ground up.

Another example is the promotion process, which is often perceived as a biased, opaque and arbitrary process at many companies. While the process might not work for certain ICs at a microlevel, the process is the way it is because it clearly works for the organization, based on whatever metrics the organization is tracking which you might not be privy to.

You can learn how the organization’s promotion process works and play your cards right. Or, if the process seems so arbitrary and unfair you feel you will never have a shot at succeeding, you can try to switch to organizations or companies where you feel you might have a fairer crack of the whip.

Your manager might be able to elaborate on the whys and wherefores of this process, but managers have competing priorities to juggle and they cannot always guarantee their primary focus will be the career growth of all of their direct reports at all times. Which, again, is why you need to understand how your organization truly works, because you might then be able to seek out people other than your manager who might mentor you to better understand the organization’s way of doing things.

Conclusion

It’s easy to dismiss much of what’s in this post as “politics”. The unfortunate reality is that almost everything is political, and beyond a certain level, advancing further requires getting really good at playing this game.

Many engineers find it far easier to label things that don’t go their way as “politics”, as opposed to introspecting and learning the hard skills required to make better judgements. “Politics” doesn’t necessarily have to be a negative thing per se, and I suspect the near ubiquitous negative connotations attached to “politics” can be attributed to the fact that a lot of engineers aren’t the most astute when it comes to navigating these nuances.

The truth is you can have a very gratifying and rewarding career as an engineer if you’re good at the “purely tech” side of things without ever worrying about the kind of problems described here.

But you’re far likelier to be one of those rare force multipliers if you’re also:

good at solving pressing problems

relentlessly getting things done

proactively creating iterative change

All of which requires understanding how your organization works.

This is Gergely, again.

Thank you to Cindy for this timely reminder on the importance of navigating your organization in order to become an effective engineer. You can follow Cindy on X, and read more of her writings on her blog.

The biggest takeaway from this article for me is this:

Software engineers frustrated at being “stuck” in their career often did no proper attempt to understand how their organization works. Answering question like:

How do people pitch ideas that leadership pays attention to?

What are activities at this workplace that tend to get rewarded?

Who are the people who are accessible to me and are “in the know” for different areas?

What is the implicit hierarchy at my workplace? Who are the most important engineers / product people that everyone seems to seek out informal advice from?

Is my workspace culture actually top-down, bottom-up, or both?

Tech companies are far more messy than any of us engineers would like to admit. I have talked with several software engineers who work at prestigious tech companies – and yet, they tell me that inside it is a surprisingly large mess. “Mess” meaning one or more of: lots of tech debt with no plan to pay it down, antiquated processes, political games, respected engineers being frustrated and on the verge of leaving.

When I worked at Skype, and then Uber, I also experienced the same: from the outside everything looked idyllic. From the inside, it felt like some parts of the company were held together either by duct tape or scaffolding that was so fragile that it was a miracle it did not collapse on itself.

It’s good to have strong ideals about what “great” is: but understand the practicalities of “good enough.” The single most frustrated engineers I worked with were ones who refused to let go of their idealistic way of working: and were upset that their organization would refuse to do things the “right” way (in their mind, that is). There is a fine line between always pushing for more and better techologies/processes/approaches: but also understanding when it’s impractical to change the status quo. And – as Cindy reminded us – always start by understanding why technologies and processes have evolved to where they are at your current workplace.