The end of 0% interest rates: what it means for tech startups and the industry

The past 15 years saw the lowest interest rates in modern history, and this “zero interest-rate period” (ZIRP) meant growing tech companies was easy. With this period over, what changes for startups?

👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a subscriber-only issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. Subscribe to get issues like this in your inbox, every week.

This article is part 1 in a 4-part series on the end of 0% interest rates. Other issues cover:

What it means for startups and the tech industry (Part 1, this one.) More pressure to achieve profitability, less venture capital funding, Big Tech gets bigger, and bootstrapping more common.

What it means for software engineers (Part 2.) A tougher job market, harder to negotiate offers, slower career growth, and higher performance expectations.

What it means for engineering managers (Part 3.) Fewer EMs, more responsibilities for the rest, the rise of the tech lead role, and an opportunity to build more cohesive teams due to lower attrition.

What it means for software engineering practices (Part 4.) Monoliths over microservices, more shifting left of responsiblities and pragmatic, simpler architecture.

For over a decade, the tech industry was a benefactor of a lengthy ZIRP in the US, which had its roots in the years 2007 and 2008, when two important events changed the course of the tech industry – although many of us probably paid closer attention to the first one:

Apple launched the iPhone (2007), and Google launched Android (2008)

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) caused interest rates to sink to zero in the US (2008)

The impact of the iPhone is undeniable; Apple created a new category with its touchscreen-only smartphone. A year later, Google responded with Android. Within a decade, iOS and Android were the only two mainstream mobile operating systems, which aided the development of mobile-first companies, such as Uber, Instagram, DoorDash, Snap, TikTok, and thousands of others.

Rock-bottom interest rates also provided a big boost to the tech industry, and helpfully coincided with the dawn of the age of the smartphone, and other tech innovations like widespread adoption of cloud computing.

Today, we cover:

What is ZIRP? And why were there close to zero interest rates globally, for so long?

What post-ZIRP means for venture capital. When low-risk investments like government bonds deliver better returns, it’s harder for startups to raise money.

Publicly traded companies and Big Tech. Lower company valuations, pressure to become profitable – and Big Tech excelling.

Late-stage startups. Post-ZIRP, it’s much harder to raise new funding, fewer IPOs, and other exits. Few options except trying to achieve profitability – even if it means deep cuts.

Early-stage startups. Post-ZIRP, investors expect more at the seed stage, and raising a Series A became very challenging. A low burn rate is table stakes.

Bootstrapped companies. Bootstrapping is back in style in our higher interest-rate world – plus, lessons from bootstrapped companies founded by software engineers are timely.

Are startups really a “low-interest-rate phenomenon?” Some finance professionals claim startups depend on low interest rates. But this thesis can be defeated with data, offering hope for tech innovation in today’s high interest-rate environment.

See also What the end of ZIRP means for software engineers.

1. What is ZIRP?

A “zero interest-rate period” is when a central bank of a country lends money at a very low interest rate – typically at or below 1% rate for overnight deposits, and usually at or below 2-4% for 10 or 20-year bonds. The term “zero interest-rate” assumes rates this low can be considered effectively as zero percent, when taking into account inflation that tends to be above 1% in most countries.

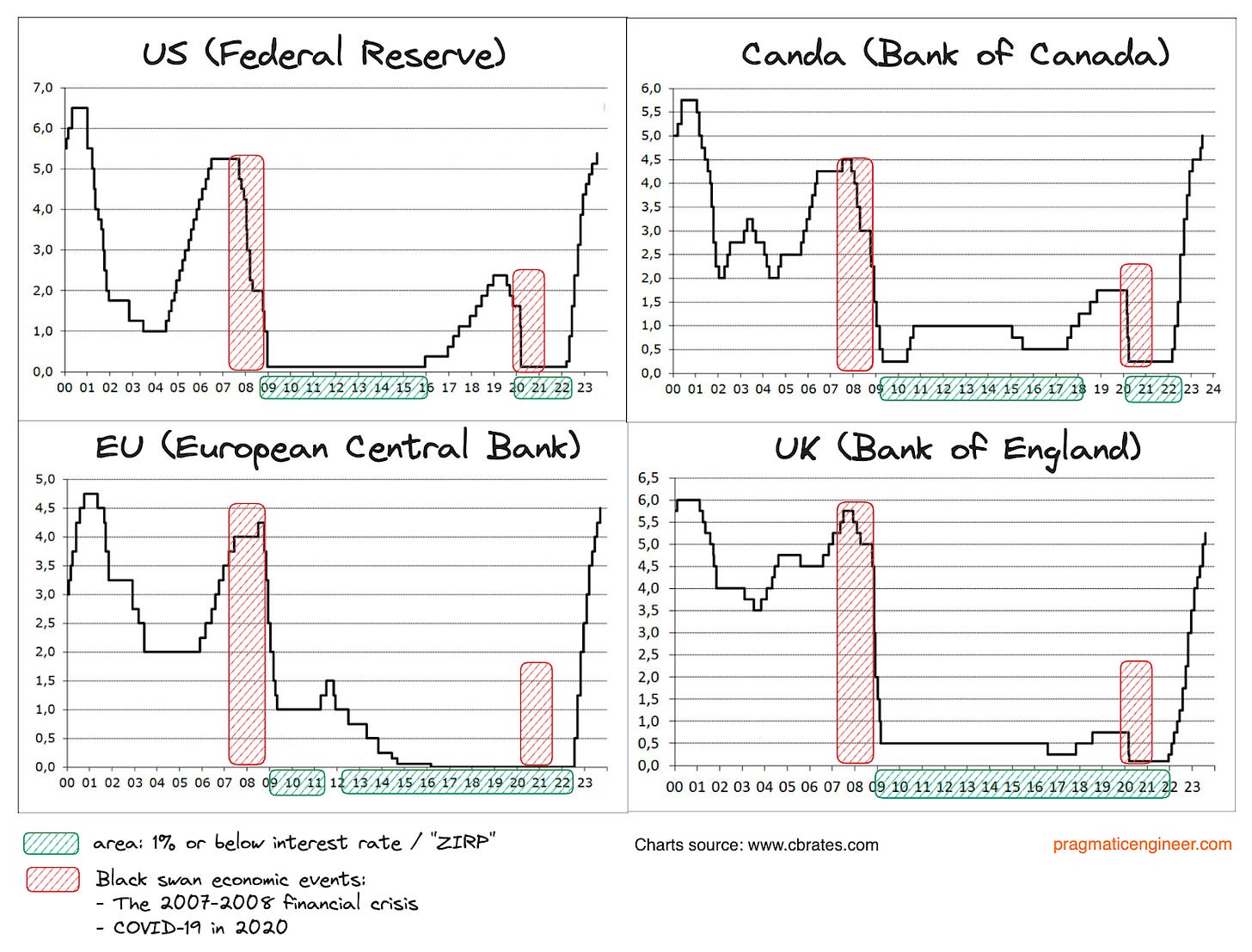

The past decade is considered a ZIRP across most of the developed world. Here’s how interest rates in the US, Canada, the EU and the UK changed in the past 20 years.

Lowering or raising central bank interest rates is part of governmental monetary policy, which usually seeks economic growth. Here’s how Investopedia summarizes what each one tends to result in:

“If the Fed raises interest rates, it increases the cost of borrowing, making both credit and investment more expensive. This can be done to slow an overheated economy.

If the Fed lowers rates, it makes borrowing cheaper, which encourages spending on credit and investment. This can be done to help stimulate a stagnant economy.”

Interest rates hit almost zero in 2008, due to the Global Financial Crisis. In 2007-2008, a huge financial crisis broke, triggered by a housing mortgage bubble in the US, and irresponsible practices by banks which caused the near-meltdown of the global financial system, and led to the bankruptcy of the overexposed Lehman Brothers bank. The 2015 movie The Big Short gives an entertaining account of the crisis – and how some profited from it.

This crisis delivered a heavy blow to the global economy, and central banks acted swiftly to counter it. The US, Canada, EU, and the UK, all lowered interest rates drastically in order to encourage spending on credit and investing. The tactic seems to have worked, at least partially. Financial armageddon was averted and economic output picked up; although US gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by 2.6% in 2009 – the first major economic contraction since 1982 – growth resumed shortly after.

From 2017, central banks in the US and Canada began to slowly raise interest rates, after their economies started to recover from the 2007-2008 shock. But in 2020, yet another “black swan event” happened: COVID-19. Once again, the global economy shrank. And once again, central banks responded by lowering interest rates to encourage investment and spur economic recovery. The rebound from the pandemic was rapid, and rates started to rise again from 2022.

Interest rate charts, showing the zero rate-interest periods of the pandemic and GFC in green:

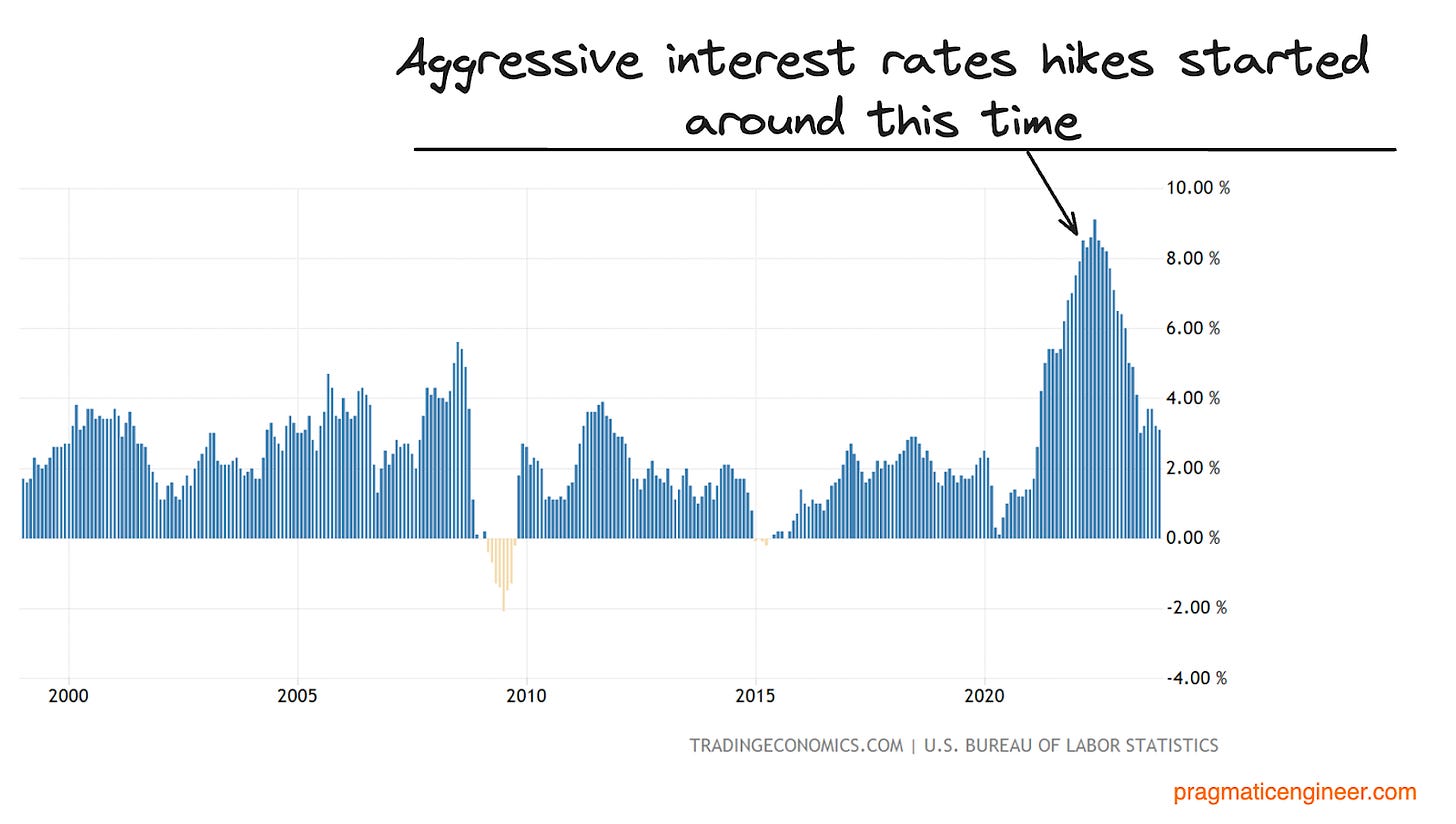

Why did interest rates skyrocket in 2022, though? It’s easy enough to understand why central banks lowered interest rates, but why did pretty much all banks raise rates from zero to nearly 5% between the start of 2022 and mid-2023. In most places, interest rates today are at a 20-year high!

In the US, the raises were in response to inflation, which started to increase steeply in 2021, and peaked at above 8% in 2022:

But how does raising interest rates bring down inflation? Here’s a brief explainer from the Bank of England, which raised rates as steeply as in the US:

“The prices you pay at the supermarket check-out, the petrol pump, and many other places have risen quickly in recent years.

Inflation is the measure of those increases. When prices are rising too quickly, the rate of inflation is high. It means you can buy less with your money than you did before. So your cost of living is higher.

The UK government sets us a target of having low and stable inflation. As the UK’s central bank, the best tool we have to slow down rising prices is interest rates.

How do higher interest rates help to slow inflation?

Interest rates on mortgages, loans and savings are at their highest level for many years. The reason for that is we are using interest rates to slow price rises in the UK. We have put up the UK base interest rate 14 times over the past two years.

Higher interest rates increase the return on savings. They also make the cost of borrowing more expensive.

Higher interest rates help to slow down price rises (inflation). That’s because they reduce how much is spent across the UK. Experience tells us that when overall spending is lower, prices stop rising so quickly and inflation slows down.”

The principle is the same in the US, Canada, EU, and elsewhere. When inflation is high, raising the interest rate reduces spending, and therefore inflation slows. There is a downside to raising central rates: economic growth also slows. Central banks balance inflation goals and growth goals.

A ZIRP is the exception and not the norm, over time. Can we expect interest rates to go down, and for ZIRP to return? It’s hard to predict; but across 70 years in the US, high rates were the norm, with close-to-zero rates much rarer:

Since 1955, the US has had around 11 and a half years of zero interest-rates – of which 11 were from 2008. It’s easy to assume it’s interest rates that are skyrocketing, but it could be they are returning to the historical norm.

It would almost certainly take a recession to bring rates back down. In this article, we look into what’s expected to happen if interest rates remain high above ZIRP-level.

2. What a higher rate means for venture capital

The “baseline” of risk-free investment increased significantly

For people and institutions with money to invest, “risk-free” returns on investments have increased by almost 10x. This includes limited partners, i,e: people and organizations funding venture capital firms.

In 2020, the 10-year US treasury note yielded 0.5-0.7% per year. In 2023, it was between 4-5% – and 4%. These bonds pay interest every 6 months and return the principal amount invested in 10 years. Here’s how much money every $1,000 invested would yield:

Returning 50% above the invested amount in 10 years is the new “risk-free” investment category. Not only that, but dividends are paid every 6 months.

It’s harder for VCs to raise funds

Venture capital is funded by investors who are usually a mix of:

High net-worth individuals

Pension funds

Wealthy families

Sovereign wealth funds

Insurance companies

They fund VC firms in order to diversify their own wealth through investments which a VC firm makes in a higher-risk and higher return asset, or because they expect better returns than from investing in government bonds, property, stocks, etc.

Government bonds are traditionally the least risky asset type. So, when the interest on a bond increases by 4-5% per year, it only makes sense to invest in VC if it offers higher returns than a low-risk government bond.

The absence of tech companies going public is sure to hurt VC firm returns, should we see so few IPOs as it’s been the case. We’re in the midst of an IPO winter: in 2022 and 2023, there were only 3 tech IPOs – all in September 2023 (Arm, Instacart, Klaviyo.) Right now, the VC asset class just doesn’t look that promising compared to government bonds, except for very high-growth areas like AI.