The Past and Future of Modern Backend Practices

From the birth of the internet, through SOA and virtualization, to microservices, modular monoliths and beyond with Joshua Burgin; tech industry veteran and one of Amazon’s first 100 employees

👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a 🔒 subscriber-only issue 🔒 of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers.

It’s fascinating how what is considered “modern” for backend practices keep evolving over time; back in the 2000s, virtualizing your servers was the cutting-edge thing to do; while around 2010 if you onboarded to the cloud, you were well ahead of the pack. If you had a continuous deployment system up and running around 2010, you were ahead of the pack: but today it’s considered strange if your team would not have this for things like web applications.

How have practices considered cutting edge on the backend changed from its early days, and where is it headed in future?

To answer this big question, I turned to an industry veteran who’s been there, seen it, and done it – and is still active in the game. Joshua Burgin was an early Amazon employee, joining in 1997, back when Amazon was just an internet bookstore and cloud computing wasn’t even a speck on the horizon.

He then worked at the casual games company Zynga, building their in-game advertising platform. After Zynga, he rejoined Amazon, and was the General Manager (GM) for Compute services at AWS, and later chief of staff, and advisor to AWS executives like Charlie Bell and Andy Jassy (Amazon’s current CEO.) Joshua is currently VP of Product & Strategy at VMware, a cloud computing and virtualization technology company. Joshua has remained technical while working as an executive.

Joshua also writes an excellent Substack newsletter about how to design products which customers love, how to operate live services at scale, grow and optimize your technology orgs, and the history of the tech industry. Subscribe here.

In this issue, we cover:

Year 1 on the job: accidentally taking Amazon.com offline

The birth of ARPANET (1969)

The rise of the internet and web-based computing (1989)

The struggle for scale at Amazon and the birth of SOA (late 1990s)

Virtualization: the new frontier (1999-2002)

Cloud computing: A paradigm shift (2006-2009)

Containers and Kubernetes: reshaping the backend landscape (2013-2019)

Today’s backend ecosystem: defining “modern”

Envisioning the future of backend development

In this article, we use the word “modern” to describe what larger, more established businesses consider cutting edge today. We also use it in a historical sense to describe previous generations of technology that were pioneering in their time. It’s important to note there are no one-size-fits-all choices with technology, especially for things like microservices or Kubernetes, which are still considered relatively modern at large companies today. Startups and midsized companies are often better off not jumping to adopt new technologies, especially ones which solve problems a business does not have.

This issue is exhaustive in contents, and the bottom of this article might be cut off in email clients. Read the full article uninterrupted online.

With that, it’s over to Joshua:

1. Year 1 on the job: accidentally taking Amazon.com offline

My journey in backend development began with an unexpected stumble, not a carefully considered first step on a pre-planned career path. In 1997, when Amazon was a one-floor, sub-100 person startup trying to sell books online, I experienced what every engineer dreads.

Backend code I wrote and pushed to prod took down Amazon.com for several hours. This incident was my initiation into the high-stakes world of internet-scale services. Back in those days, the “cloud” wasn’t even something you could explain with hand gestures, and of course not something to which you deployed applications, and scaled on a whim.

Our tools were simple: shell scripting, Perl (yes, really!) and hand-rolled C-code. We used a system called CVS (Concurrent Versions System) for version control, as Git did not exist until 2005 when Linus Torvalds created it. Our server setup was primitive by today's standards; we had a single, full-rack size “AlphaServer” box manufactured by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC):

On the Alpha box, we had an “online” and “offline” directory. To update code, we flipped a symlink (a symbolic link is a file whose purpose is to point to a file or directory) to swap between the code and HTML files contained in these directories. At the time, this approach was our best effort to deliver code on the nascent web.

Amazon.com ran on top of a monolithic C binary named “Obidos,” named after the narrowest, swiftest section of the Amazon river, in Brazil. Obidos shouldered the entire load of a business which became an online retail behemoth.

I remember the physicality of our systems; the blinking lights of the network traffic, having to put thermometers on servers because we were using converted conference rooms as data centers, and how we put a tarp in one corner because the roof leaked! All our servers had names, including some named after Muppets characters like Bert and Ernie.

We didn’t build our applications in neat containers, but in bulky monoliths which commingled business, database, backend, and frontend logic. Our deployments were initially manual. Avoiding downtime was nerve-wracking, and the notion of a 'rollback' was as much a relief as a technical process.

To succeed as a software engineer, you needed to be a jack-of-all-trades. We dabbled in network engineering, database management, and system administration. Oh, and did I mention this was on top of writing the code which fueled Amazon's growth? We were practicing varying shades of DevOps before it existed as a concept.

On the day I broke the site, I learned the importance of observability. I mean “importance” as a fundamental necessity, not a buzzword. Here’s how the outage played out:

I pushed code from dev to staging using a script where everything worked fine.

I then half-manually pushed code from staging to production. I still used a script, but had to specify parameters.

I inadvertently specified the wrong parameters for this script. I set the source and destination Apache configuration as the same.

Rather than failing with an error, this encountered an existing bug in the DEC Unix “copy” (cp) command, where cp simply overwrote the source file with a zero-byte file.

After this zero-byte file was deployed to prod, the Apache web server processes slowly picked up the empty configuration file. And it lost pointers to all its resources!

Apache started to log like a maniac. The web server began diligently recording logs and errors it encountered.

Eventually, the excessive Apache logs exhausted the number of inodes you can have in a single directory

Which resulted in the servers becoming completely locked up!

To resolve this, we had to do a hard reboot. This involved literally pushing the power button button on the server!

Our ability to monitor what was happening for users on the website was overly simple, it turned out. It’s wasn’t that we hadn’t thought about monitoring because we automated plenty of things, such as:

Network monitoring: inbound/outbound traffic

Database monitoring: for example, keeping track of order volume

Semi-automated QA process for our “dev” and “staging” environments

Of course, we had no synthetic monitoring back then; as in simulating website usage, and thereby getting notified when things went wrong before users experienced it. Instead, we were regularly notified of bugs when executives’ spouses and partners encountered issues while trying to buy things!

Looking back, I could’ve done a better job with bounds checking and input validation. By bounds checking, I mean determining whether an input variable is within acceptable bounds before use and input validation. And for input validation, I mean that I could have analyzed inputs and disallowed ones considered unsuitable. I made these improvements after the outage, as part of the post-mortem process, which at Amazon is known as a “COE” (Correction of Errors,) and uses the “5 whys methodology” developed originally at Toyota, which is still common today across the US. The AWS re:invent conference in 2022 hosted a good in-depth overview of Amazon’s COE process.

“The more things change, the more they stay the same,” is one theme of this article. And this was proved true not long after I returned to Amazon in 2014, when a very large AWS service outage was caused by… you guessed it; the absence of bounds checking and parallelized execution.

The outage I caused in 97 taught me that developing robust systems goes hand-in-hand with the development of robust monitoring and observability tooling – which should exist outside of whatever code you’re writing because you can’t always anticipate how your code will operate. And of course the incident was a lesson in humility and accountability, demonstrating that how you respond to outages or problems you cause, is a reflection of your character and professional integrity. Nobody’s perfect, and reacting positively to challenges and critical feedback significantly enhances how others perceive you.

But this article isn't just about learning from the past; it's about understanding the roots of current backend engineering practices. Let’s dive into the evolution of backend development, from computing’s early days up to the present, and try and predict what the future holds. As we go on this journey, remember:

Every complex system today stands on the shoulders of lessons from earlier, formative times.

2. The birth of ARPANET (1969)

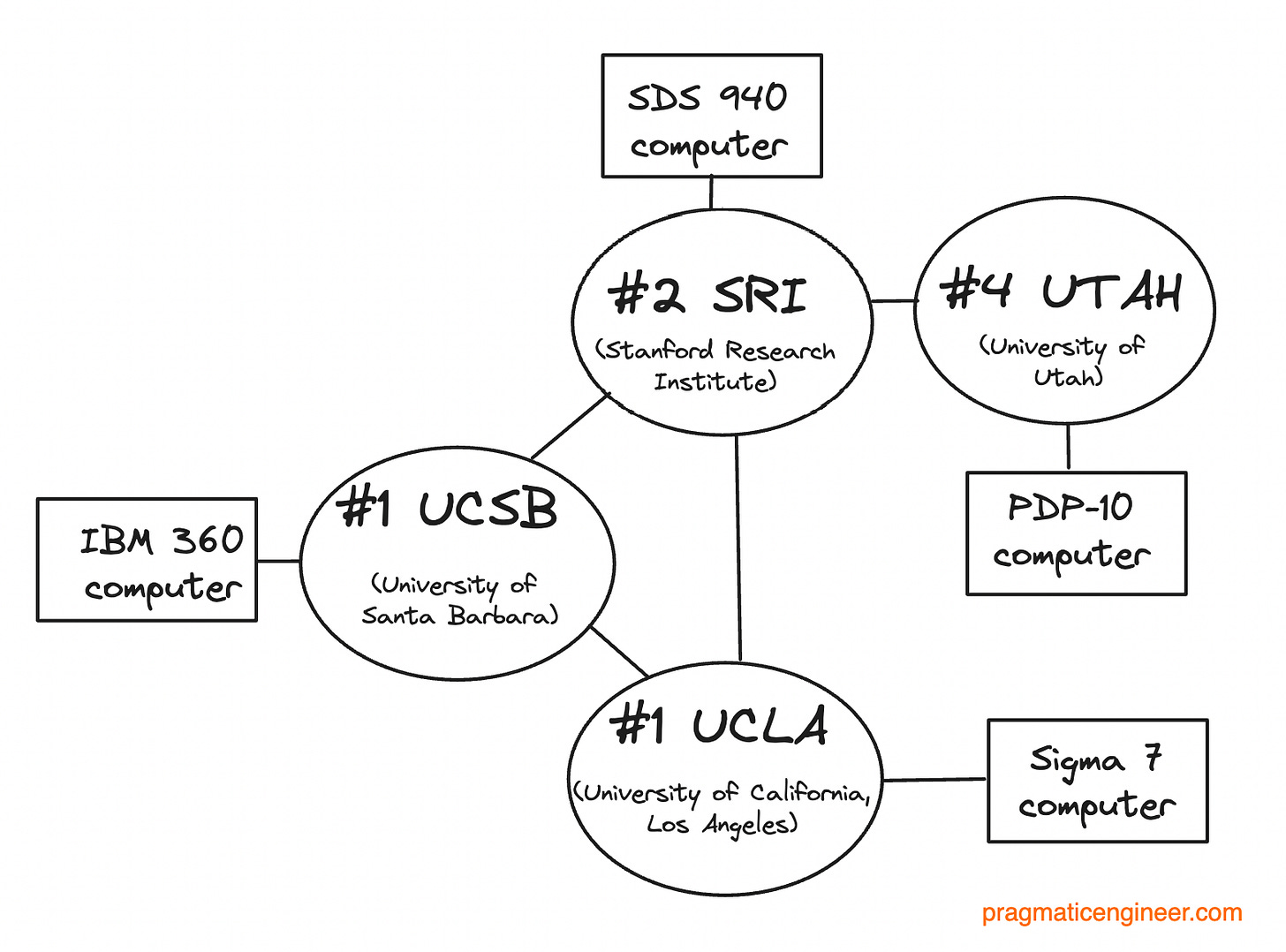

To appreciate the magnitude of progress in backend development, we need to go back to 1969 and the birth of ARPANET. This pioneering project was conceived during the Cold War between the US and the USSR. ARPANET was the world’s first major foray into networked computing. This project’s advancements laid the groundwork for many technologies still with us today, seven decades later.

The concept of a distributed network was revolutionary, back then. ARPANET was designed to maintain communications during outages. This is a principle that has since become a cornerstone of modern backend architecture. But back then, the challenge wasn't just in building a network; it was about proving distributed systems could be reliable, efficient, and secure, on a scale never attempted before.

Consistent experimentation was a hallmark of this era. Protocols and practices we now regard as rudimentary were cutting-edge breakthroughs.

Packet switching was the method ARPANET used to send data, which laid the foundation for the future internet. In the early 1960s the prevailing communication networks consisted of continuous, analog circuits primarily utilized for persistent voice telephone connections. This approach was transformed by the advent of packet switching, which introduced a digital, intermittent framework for networks. This method transmits data in discrete packets, doing so only as needed. Although this introduced the compromises of signal discontinuity and conversion overhead, packet-switching had several advantages:

Digital signal could be made "error-free"

Software processing was upgradeable at the connection points

Redundancy meant networks could survive damage

Sharing links boosted efficiency

For more on how packet switching works, this overview on the Engineering & Technology History Wiki is a good start, and it also provides details on how ARPANET was originally connected:

“ARPANET was linked by leased communication lines that sent data at speeds of fifty kilobits per second. Operating on the principles of packet switching, it queued up data and subdivided it into 128-byte packets programmed with a destination and address. The computer sent the packets along whichever route would move it fastest to a destination.”

Sending digital packages allowed for robust, adaptable communication pathways that could withstand points of failure. This resistance to failure is what modern cloud services replicate in their designs for fault tolerance and high availability.

There were a lot of technical hurdles which ARPANET had to overcome. The biggest was how to create a network that operated across disparate, geographically separated nodes. To solve this, network engineers devised innovative solutions that went on to influence the development of protocols and systems which underpin today’s web. For example, this was when these protocols were invented:

All these protocols were built for or, first implemented, on ARPANET!

As a backend developer, acknowledging ARPANET's influence is vital. The engineers who built ARPANET show us the importance of expecting and designing for failure, which is the core principle of backend and distributed systems development practices today. Notions of redundancy, load balancing, and fault tolerance which we work with are the direct descendants of strategies devised by ARPANET’s architects.

3. The rise of the internet and web-based computing (1989)

ARPANET's influence expanded in the 1980s when the National Science Foundation Network (NSFNet) provided access to a network of supercomputers across the US. By 1989, the modern Internet as we know it was born, The first commercial Internet Service Providers (ISPs) emerged in the US and Australia, kicking off a radical shift in global communication.

At the same time as the first ISPs were founded, in 1991 Sir Tim Berners-Lee proposed and implemented the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP.) It defined internet-based communications between a server and a client. HTTP triggered an explosion in connectivity – and we can now safely say this protocol proved to be one of two fundamental catalysts of rapid internet adoption.

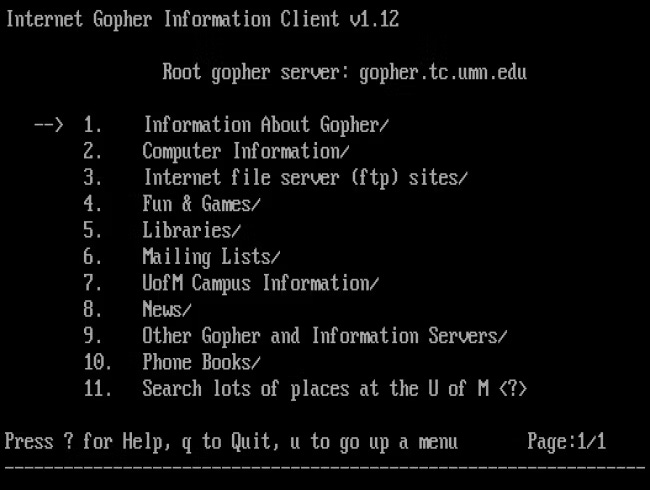

What was the other driver of adoption? Well, until 1993, the most common way to access the internet was via text-based interfaces, and the Gopher browser, which looked like this:

Then in 1993 Marc Andreessen and his team built and launched the first modern web browser, Mosaic, which provided a graphical interface for browsing the internet, making it accessible to a non-technical audience. This milestone is widely considered a critical point in the digital revolution, by enabling the average person to easily and meaningfully engage with online information and resources.

Scaling challenges became more interesting on the backend side of things. As the internet's reach grew, businesses faced the daunting task of making their infrastructure available on this thing called the “internet,” and scaling it to allow more users to access their services at once. There were several parts of this challenge:

Serving international audiences: All code, databases, HTML web pages, customer service tools, etc., were in english only. The localization (l10n) and internationalization (i18n) projects were many months-long undertakings just to launch amazon.de (Germany.) Later, adding support for “double-byte characters” to launch amazon.jp (Japan) took just as long.

Managing increasing, unpredictable website loads: Amazon was growing tens-of-thousands-of-percent a year by order volume (and 100s of percent in staffing.) Third-party events like “Oprah’s book club” could send traffic and orders spiking 1000s of percent. And 1998 was the beginning of Amazon’s “peak season spike,” with a significant increase in sales the day after Thanksgiving, and the Christmas holidays. Even within that period there were waves, peaks and valleys that varied by several orders of magnitude.

Safeguarding data and systems: There weren’t common tools like public/private key encryption, role-based-access-control (RBAC), zero-trust, least-privilege and other “defense in depth” measures that we have today. For example, it used to be common to check your database password into your version control system, and at most obfuscate the password (i.e. by rotating the letters using a ROT13 cypher,) to reduce the risk of storing it plain-text. Clearly, something more secure was needed.

The early ‘90s also saw the emergence of novel solutions to challenges such as:

Database management

Server clustering

Load balancing

Today, these challenges still exist but are so much easier to solve, with no shortage of open source or commercial solutions. But 30 years ago, these problem areas demanded hands-on expertise and in-house, custom development.

At Amazon.com, we had our fair share of backend infrastructure challenges. The business was founded in 1994, a year after the Mosaic browser, and grew fast. This rapid growth put constant stress on the infrastructure to just keep up; not to mention Amazon’s stated ambition of becoming a global marketplace.

Internally, we seemed to hit another hard scaling limit every 6 months. This limit was almost always on how much we could scale out monolithic software. Each time we hit such a limit, we were pushed further into implementing distributed systems, and figuring out how to scale them up for demand.

At the time, it felt like Amazon was forever one bad customer experience away from going under. It was a high-pressure environment, and yet we needed to build systems for the present, and also for unpredictable but ever-increasing future loads.