When AI writes almost all code, what happens to software engineering?

No longer a hypothetical question, this is a mega-trend set to hit the tech industry

This winter break was an opportunity for devs to step back from day-to-day work and play around with side projects – including using AI agents to juice up those half-baked or incomplete ideas. At least, that’s what I did with a few features I’d meant to build for months, but didn’t get around to during 2025: related to self-service group subscriptions for larger companies, and my custom-built admin panel for The Pragmatic Engineer.

Unexpectedly, LLMs like Opus 4.5 and GPT 5.2 did amazing jobs on the mid-sized tasks I assigned them: I ended up pushing a few hundred lines of code to production simply by prompting the LLM, reviewing the output, making sure the tests passed (and new tests I prompted also passed!), then prompting it a bit more for some final tweaking.

To add to the magical feeling, I then managed to build production software on my phone: I set up Claude Code for Web by connecting it to my GitHub, which let me instruct the Claude mobile app to make changes to my code and to add/run tests. Claude duly created PRs that triggered GitHub actions (which ran the tests Claude couldn’t) and I found myself reviewing and merging PRs with new functionality purely from my mobile device while travelling. Admittedly, it was low-risk work and all the business logic was covered by automated tests, but I hadn’t previously felt the thrill of “creating” code and pushing it to prod from my phone.

This experience, also shared by many others, suggests to me that a step change is underway in software engineering tooling. In this article – the first of 2026 for this publication – we explore where we are, and what a monumental change like AI writing the lion’s share of code could mean for us developers.

Today, we cover:

Latest models create “a-ha” moments. It’s not just devs working at AI vendors who noticed much more capable models, but also independent software engineers.

Why now? Model releases in November and December seem to have been the tipping point: Opus 4.5, GPT-5.2 and Gemini 3.

The bad: declining value of expertise. Prototyping, being a language polyglot or a specialist in a stack are likely to be a lot less valuable, looking ahead.

The good: software engineers more valuable than before. Tech lead traits in more demand, being more “product-minded” to be a baseline at startups, and being a solid software engineer and not just a “coder” will be more sought-after than before.

The ugly: uncomfortable outcomes. More code generated will lead to more problems, weak software engineering practices start to hurt sooner, and perhaps a tougher work-life balance for devs.

Product management vs software engineering: merge or separation? Product managers can now generate software easier – needing fewer engineers to realize their goals – but software engineers also need less product management. Both professions are set to overlap with another more than before.

1. Latest models create “a-ha” moments

Over the past few weeks, some experienced software engineers have shared personal “a-ha” moments about how AI tooling has become good enough to use for generating most of the code they write.

Jaana Dogan, principal engineer at Google, was very impressed by how far Claude Code has come:

“I’m not joking and this isn’t funny. We have been trying to build distributed agent orchestrators at Google since last year. There are various options, not everyone is aligned, etc. I gave Claude Code a description of the problem, it generated what we built last year in an hour.

It’s not perfect and I’m iterating on it, but this is where we are right now. If you are skeptical of coding agents, try it on a domain you are already an expert in. Build something complex from scratch where you can be the judge of the artifacts”.

Thorsten Ball, software engineer at Amp reflected (emphasis mine):

“For more than 15 years, I thought I loved writing code, loved typing out code by hand, and loved the “cadence of typing”, as Gary Bernhardt once called it; sitting in front of my editor with my fingers click-clacking on my keyboard.

Now, I’m not so sure.

2025 was the year in which I deeply reconsidered my relationship to programming. In previous years, I had the occasional “should I become a Lisp guy?”, for sure; but not the question “do I even like typing out code?”

What I learned over the course of the year is that typing out code by hand now frustrates me”.

Malte Ubl, CTO at Vercel:

“It’s been a crazy holiday period: I built 2 major open-source projects (one unreleased, and the other a full implementation of a bash environment in TypeScript for use by AI agents).

I started writing a book

I fixed a bunch of other things

It’s a very different world now that we’re in Opus 4.5 world, and these would absolutely not have been possible without it. Opus + Claude Code now behaves like a senior software engineer whom you can just tell what to do, and it’ll do it. Supervision is still needed for difficult tasks, but it is extremely responsive to feedback and then gets it right.

I don’t want to be too dramatic, but y’all have to throw away your priors. The cost of software production is trending towards zero”.

Longtime readers may recall Malte from his reflections on 20 years in software engineering, including 11 at Google.

One could claim that the voices above have an interest in this topic given they work at companies selling AI dev tools. But engineers with no pull towards any vendor also made similar observations:

David Heinemeier Hansson (DHH), creator of Ruby on Rails, described how his stance on AI has flipped due to the improved models:

“You can’t let the slop and cringe deny you the wonder of AI. This is the most exciting thing we’ve made computers do since we connected them to the internet. If you spent 2025 being pessimistic or skeptical about AI, why not start 2026 with optimism and curiosity?

Just last summer, I spoke with Lex Fridman about not letting AI write any code directly, but it turns out part of this resistance was simply based on the models not being good enough at the time! I spent more time rewriting what it wrote, than if I’d done it from scratch. That has now flipped.”

Adam Wathan, creator of Tailwind CSS, reflected:

“Any time I have to type precise syntax by hand now [instead of using AI] feels like such a tedious chore. Surprisingly and thankfully, programming is still fun, probably more fun [with LLMs].

My biggest problem now is coming up with enough worthwhile ideas to fully leverage the productivity boost.”

From “AI slop” to rocking the industry

One widely circulated “a-ha” moment has been from Andrej Karpathy, a cofounder of OpenAI. Andrej has not been involved in OpenAI for years, and is known to be candid in his assessment and critique of AI tools. Last October, he summarized AI coding tools as overhyped on the Dwarkesh podcast (emphasis mine):

“Overall, the models are not there. I feel like the industry is making too big of a jump and is trying to pretend like this is amazing, and it’s not.

It’s slop.

They’re not coming to terms with it, and maybe they’re trying to fundraise or something like that. I’m not sure what’s going on, but we’re at this intermediate stage. The models are amazing. They still need a lot of work.

For now, autocomplete is my sweet spot. But sometimes, for some types of code, I will go to an LLM agent”.

Two months on, that view had been thoroughly revised, with Karpathy writing on 26 December (emphasis mine:)

“I’ve never felt this much behind as a programmer.

The profession is being dramatically refactored as the bits contributed by the programmer are increasingly sparse. I have a sense that I could be 10X more powerful if I just properly string together what has become available over the last ~year, and a failure to claim the boost feels decidedly like a skill issue.

There’s a new programmable layer of abstraction to master in addition to the usual layers involving agents, subagents, their prompts, contexts, memory, modes, permissions, tools, plugins, skills, hooks, MCP, LSP, slash commands, workflows, IDE integrations, and a need to build an all-encompassing mental model for strengths and pitfalls of fundamentally stochastic, fallible, unintelligible and changing entities suddenly intermingled with what used to be good old fashioned engineering.

Clearly some powerful alien tool was handed around, except it comes with no manual and everyone has to figure out how to hold and operate it while the resulting magnitude 9 earthquake is rocking the profession.

Roll up your sleeves to not fall behind”.

The creator of Claude Code, Boris Cherny, responded, sharing that all of his committed contributions last month were AI-written:

“The last month was my first as an engineer when I didn’t open an IDE at all. Opus 4.5 wrote around 200 PRs, every single line. Software engineering is radically changing, and the hardest part even for early adopters and practitioners like us is to continue to re-adjust our expectations. And this is *still* just the beginning”.

We previously did a deepdive on how Claude Code was built with Boris and other founding members of the team.

2. Why now?

Model releases in November and December seem like the tipping point where AI got really good at generating code:

Gemini 3 by Google (17 November): Google’s best coding model to date

Opus 4.5 by Anthropic (24 November): the best coding model from the company, which has become the default model for Claude Code

GPT-5.2 by OpenAI (11 December): powering Codex, it’s similarly impressive as Claude Code with Opus

I’ve used both Opus 4.5 and GPT-5.2 and they seem very competent at coding, which isn’t a niche opinion. Here’s Peter Steinberger, a software engineer with ~20 years’ experience and the creator of PSPDFkit, gave his impression of GPT-5.2:

“The step from GPT 5/5.1 to 5.2 was massive. Now that GPT 5.2 is out, I have far fewer situations where I need [a custom-built CLI agent called ‘oracle’ to get the agent unstuck]. I do use [GPT 5] Pro myself sometimes for research, but the cases where I asked the model to “ask the oracle” went from multiple times per day to a few times per week.

I’m not mad about this; building ‘oracle’ was super fun and I learned lots about browser automation, Windows, and finally took time to look into skills, having dismissed the idea for quite some time. What it does show is how much better 5.2 got at many real-life coding tasks: it one-shots almost anything I throw at it”.

Simon Willison is an independent software engineering expert in LLMs whom I pay attention to, and he pointed out the same:

“It genuinely feels to me like GPT-5.2 and Opus 4.5 in November represent an inflection point - one of those moments when the models get incrementally better in a way that tips over an invisible capability line. Suddenly, a whole bunch of much harder coding problems open up.

It’s possible Gemini 3 Pro should be included in that group as well, but I’m not seeing quite the same level of astonished buzz from hardened software engineers around that model that I am for the other two”.

The first-ever The Pragmatic Engineer Podcast episode was with Simon, fittingly entitled AI tools for software engineers, but without the hype – and Simon continues to live up to that sentiment.

Wild prediction coming true?

One forecast which many – including me – were sceptical about was made by Anthropic’s CEO, Dario Amodei, last March, when he said:

“I think we will be there in three to six months, where AI is writing 90% of the code. And then, in 12 months, we may be in a world where AI is writing essentially all the code”.

Yet it came to pass in December, when 100% of Cherny’s code contributed to Claude Code was AI-written. Playing devil’s advocate, one could point out that Claude Code is closed source, so the claim is hard to validate. And of course, the creator of something like Claude Code wants to showcase its high-performance capabilities. But I’ve talked with Boris and trust him; also, my own experience of using Claude Code tallies with his: I let Claude Code generate all the code I end up committing.

When the code is not how I want it, I do more prompting to get the LLM to fix it. Like Boris, I’ve ceased writing code by hand because I don’t have to do it, and the models seem capable enough. I can still do it, but it’s simply faster to leave it to the model.

Even for code that I know well enough and can navigate in my IDE, I’ve noticed that prompting the agent can get edits done just as quickly as I would do it, if not faster. Nonetheless, I do find myself going to the IDE as I like to know that I can do the work.

For my own use case, the claim feels true enough that AI can generate 90% of the code I write, using TypeScript, Node/Express, React, and Postgres as technologies, in my case. I understand the same is increasingly true of languages like Go, Rust and other popular languages and frameworks which LLMs have plenty of training data for. Interestingly, LLMs seem to be pretty good at C as well, as observed by Redis creator, Salvatore Sanfilippo.

The remainder of this article assumes AI coding tools WILL become good enough to generate ~90%+ of the code for many devs and teams, this year. The most likely candidates for this landmark look like being startups seeking product-market fits – for whom throwaway work is no big deal – and also greenfield development projects, where no existing codebase needs to be ingested or understood before building something new.

Of course, there will also be plenty of occasions when it won’t make sense to totally rely on AI coding tools, either due to them not working well enough in some codebases or contexts, or when devs purposefully choose not to lean on them.

It’s worth exploring the directions in which the software engineering profession could go in environments where almost all code is generated by AI via prompts, rather than being typed out by a developer. This would be a sea change that impacts the profession, but how? Let’s run the rule over the good, bad, and the ugly possibilities, starting with potential negatives.

3. The bad: declining value of expertise

Some things that used to be valuable will be mostly delegated to the AI:

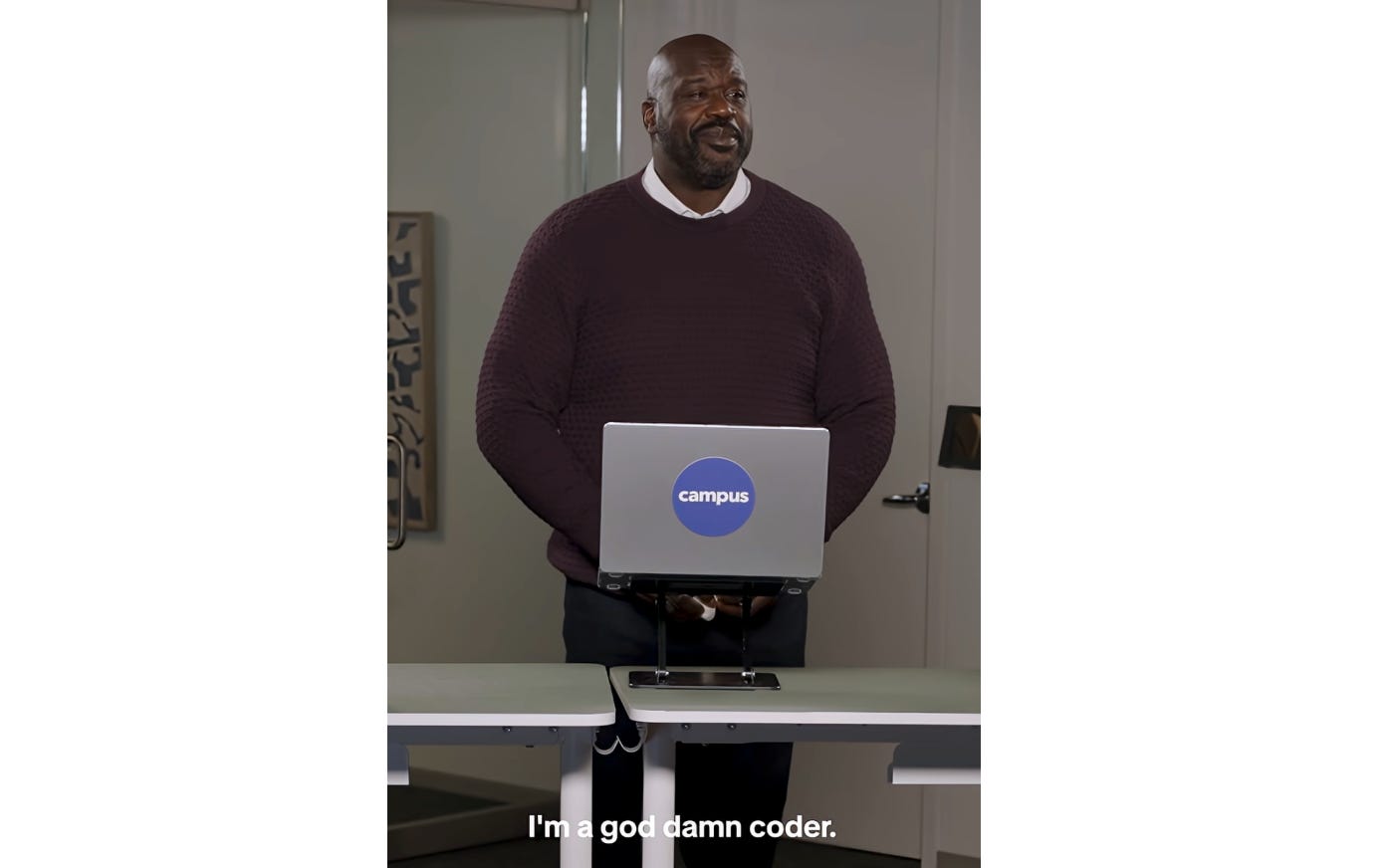

Prototyping. Platforms like Lovable and Replit explicitly advertise themselves as ways for nontechnical folks to build software. In a recent ad, Replit teamed up with legendary NBA star Shaquille O’Neal, who vibe-coded an app for getting the top 5,000 pickup lines in online history, among others:

Still, with AI tools, product folks, designers, and business people can build their own prototypes, and no longer need a dev to make an idea real. Alongside this, it’ll become a baseline expectation for each and every developer to be able to generate concept apps fast.

Being a language polyglot will probably be less valuable. Engineers who are experts in multiple languages have traditionally been coveted because engineering teams often like to hire experts in their own stack. So, a team using Go would often prefer to hire senior engineers with Go knowledge, and the same with Rust, Typescript, etc. I’d qualify this with the fact that some forward-thinking teams ignore candidates’ expertise in their specific language and assume that competent engineers can pick up languages on the go.

But with AI writing most of the code, the advantage of knowing several languages will become less important when any engineer can jump into any codebase and ask the AI to implement a feature – which it will probably take a decent stab at. Even better, you can ask AI to explain parts of the codebase and quickly pick up a language much faster than without AI tools.

The end of language specializations and frontend/backend specializations? In the early 2000s, I recall most job adverts wanted candidates for a specific language: ASP.NET developer, Java developer, PHP developer, and so on. From the mid-2010s, more companies started to hire based on specialization in the stack: backend developer, frontend developer, native iOS/Android developer, cross-platform mobile developer. On the backend, it became accepted that a dev who knew a language like Go pretty well could pick up Typescript, Scala, Rust or other languages as necessary. Roles where for specific languages still matter were for native mobile, where the iOS and Android frameworks were different enough to require deep expertise in one or the other.

But today with AI, a backend engineer can prompt decent frontend code, cross-platform code, or even attempt native mobile code. With this tool, I struggle to foresee startups hiring separate frontend and backend devs: they’ll just hire a specialist whom they trust will use AI to unblock themself across the stack.

Implementing a well-defined ticket is something AI will increasingly do, like taking a JIRA or Linear ticket that’s well-defined – like a bug report or small feature request – and implementing it. Even today, the team at Cursor has an automation where all Linear tickets are automatically passed to Cursor, which one-shots an implementation. A dev can then choose to merge it or iterate on it. The more context is passed and the better the models are, the more likely the output will be mergeable.

This will be a major shift, especially in hierarchical workplaces where project or product managers have long been writing detailed tickets for devs to implement with no questions asked!

Refactoring will probably be ever more delegated to AI. It’s already pretty good at refactoring and the tools will probably only get better. Refactoring by hand will be much slower than spelling out what type of refactor you want the AI to do. Of course, in the pre-AI era, modern IDEs also offered powerful refactoring capabilities for speeding up tedious tasks like renaming functions or classes that did the renaming across the entire codebase, extracting functions.

Of course, there will always be the risk that AI messes things up, especially with large refactorings. This is why having ways to validate code will surely be even more important this year.

Paying careful attention to generated code – in some cases? Generating code from AI prompts can lead to verbose code, or duplication of existing code instead of using an abstraction. But there are times when this is perfectly acceptable, such as when building proof of concepts, or when topics like program efficiency are unimportant.

Software engineer Peter Steinberger is building greenfield software, and said he’s stopped reading code generated by AI:

“These days, I don’t read much code anymore. I watch the stream and sometimes look at key parts, but I gotta be honest, most code I don’t read. I do know where components are and how things are structured, and how the overall system is designed; that’s usually all that’s needed.

The important decisions these days are language/ecosystem and dependencies. My go-to languages are TypeScript for web stuff, Go for CLIs and Swift if it needs to use macOS stuff, or has UI. Go wasn’t something I gave the slightest thought even a few months ago, but eventually I played around and found that agents are really great at writing it, and its simple type system makes linting fast”.

Even so, reading code will remain important when extending existing mature software, or when security issues need to be avoided. In general, if shipped code doesn’t work and hurts the business, then you’ll want to both test and review it for correctness.