Why reliability is hard at scale: learnings from infrastructure outages

What are the lessons of large outages at Heroku, Google Cloud, and Neon? Plus, how responses to outages can be as informative as incidents themselves…

This article digs into what happens when things go wrong at large-scale infrastructure providers. Last month, several well-known companies in this segment suffered widespread outages, and engineering teams later shared postmortems of what went wrong, and what they learned.

Of course, many startups never get large enough to operate tens of thousands – never mind millions – of virtual machines (VMs) as infrastructure. Nonetheless, it’s interesting to look into the challenges of operating at scale, and doing so can be a cheap, effective educational tool.

Indeed, research for this article has found that the danger of not learning from others’ experiences is very real: one major outage we cover seems to have been due to almost identical factors as caused DataDog's biggest-ever outage in 2023: the same OS (Ubuntu 22.04), same process (systemd), and same issue (the restart clearing networking routes).

We cover:

Heroku: a case of when reliability ceases to be an obsession. Heroku went completely down for 23 hours, but their response looked slow-motion, and was the least transparent of all providers. A cautionary tale of when reliability takes a backseat?

Google Cloud: globally replicating a config triggers a worldwide outage. Failing open would have reduced the impact, and using feature flags for risky updates could have cut the outage duration by two thirds.

Neon: Despite being PostgreSQL experts, this company suffered typical PostgreSQL failure modes when scaling up, such as query plan drift and slow vacuum. A reminder that if this serverless PostgreSQL scaleup can get tripped up unexpectedly by databases with millions of rows, then anyone can.

1. Heroku: when reliability is no longer an obsession

Heroku used to be a wildly popular platform-as-a-service (PaaS) provider for Ruby applications. Salesforce acquired the startup in 2010 and the founders remained there until 2013. The platform is less popular today, but in our 2025 survey it is still the second most-popular PaaS service outside of the “Big Three” clouds. As per the survey, devs use Heroku less than Vercel, but more than Hetzner and Render.

On Tuesday, 10 June, Heoku went down for nearly a full day, making it the longest-ever outage for the service. To put this in context, in the early days even a sub-2-hour outage at the company was a big deal. Back then, the Heroku team acknowledged an issue a few minutes after it started, isolated the problem within an hour, and resolved it in another 30 minutes. The company then reprioritized ongoing projects to fix the root cause, and sincerely apologized to customers. Detailed postmortems were published the day after incidents.

Things look different in 2025, as shown by the timings of Heroku’s latest outage:

8 hours to publicly acknowledge a global outage

11 hours to isolate the issue

23 hours to resolve the outage

5 days to publish a postmortem

… and no real published improvements a month later

Everything about how Heroku handled its latest outage and postmortem bears the hallmarks of a company that has gone from being obsessed with reliability back in the 2010s, to it being a backseat issue, today.

What went wrong (and what Heroku didn’t say)

The incident report is lengthy but contains few specifics. I’ve taken the liberty of filling in some gaps about what was probably Heroku’s longest-running outage, ever.

An automatic Ubuntu update broke a good chunk of Heroku for a day. The company served up a word salad about the outage with little of substance:

“The Technology team’s post-incident investigation identified the primary root cause as a gap in environment controls. This control gap allowed an unsanctioned process to initiate an automated operating system update on production infrastructure where such updates should have been disabled.

During the update, the host's networking services were restarted and were disrupted because the routes were not re-applied, severing outbound network connectivity for all dynos on the host. This occurred because the networking service applied correct routing rules only on the initial boot. The loss of routing introduced multiple secondary effects:

Recently restarted Common Runtime applications had incorrect routing rules applied. This effect increased throughout the early part of the incident affecting up to about 1% of common runtime applications at its peak at 14:10 UTC before applications started to recover.

Automatic database failovers were triggered for about 5% of HA [High Availability] postgres addons and about 10% of Non-HA addons. These failovers only resulted in small gaps in network connectivity and were largely hidden due to the dyno network failures.

The Technology team disabled automated system updates, and the team updated the affected network script to handle restarts”.

Heroku does not mention Ubuntu, but writes about “an automated operating system update on production infrastructure.” This OS running in production will be Linux, and Heroku’s infrastructure runs on Ubuntu, according to themselves. So, it must have been an automated Ubuntu update, but which one? Six days before the outage, Heroku was running Ubuntu 22.04, and 5 days after the outage it still was.

Therefore, the issue must have been with Ubuntu 22.04 updating itself and breaking Heroku in the process.

The problem which knocked Heroku offline was most likely a systemd update on Ubuntu 22.04 that messed up networking. A day before the outage, a new version of systemd was released for Ubuntu. Longtime readers might recall that systemd was at the heart of Datadog’s $5M outage in 2023. A recap on systemd:

“systemd is a "system and service manager” on Linux, that’s an initialization system, and is the first process to be executed after the Linux kernel is loaded, and is assigned the process “ID 1.”

systemd is responsible for initializing the user space, and brings up and initializes services while Linux is running. As such, it’s core to all Linux operating systems.”

So, what happened? Here’s a summary from a GitHub issue opened on the Kubernetes repo:

On 9th of June, a new version of systemd 249.11-0ubuntu3.16 was released. During the Ubuntu unattended-upgrades, this package was upgraded on all Kubernetes nodes, which triggered the systemd-networkd service to restart as well. Hence, we started to have hundreds of Pods in CrashLoopbackOff.

After investigating, this proved to be the explanation. The default behaviour of systemd-networkd is to flush ip rules that are not managed by it. In this case, all per-pod aws-vpc-cni-created ip rules were removed when systemd-networkd restarted, leaving ALL running pods without routing in place. We started to see most of them in CrashLoopbackOff, the ingress controllers affected, so basically a full downtime. To recover, we had to kubectl rollout restart, which forces the Pods replacement, including the aws-vpc-cni ip rules configs to be recreated.

Summarizing what happened:

Ubuntu ran its unattended upgrades. Ubuntu versions auto upgrade themselves, as is normal for most services. Upgrades are nothing major: there is not even a minor version upgrade for the OS itself.

The systemd process is upgraded, then restarted. systemd is a key process on Linux, and this upgrade brings in a new binary.

Due to the restart, machines lost networking capability. For machines controlling Heroku’s Kubernetes infrastructure, this upgrade was disastrous: it removed all routing for existing VMs (or, as Heroku calls them, dynos). Heoku still had dynos running, but lost their IP tables, and could not make HTTP outbound requests.

Dynos went “black.” Any sites hosted on dynos that had this auto upgrade executed stopped responding. Customers saw their sites and apps go down.

All internal tools & Heroku infra affected. “Our internal tools and the Heroku Status Page were running on this same affected infrastructure. This meant that as your applications failed, our ability to respond and communicate with you was also severely impaired.” Oops!

There’s much detail that would be good to also know, but Heroku doesn’t tell us, such as:

Does Heroku’s key infra run on the same configuration as dynos (on Heroku 22.04), and with the same config? The answer is likely “yes”, from this outage

Did all updates happen roughly at the same time across Heroku’s fleet, or were they spread out?

If spread out, how did the team not connect the updates and dynos going down?

If simultaneously, why did Heroku allow simultaneous updates across their fleet? Was this a deliberate decision, or just one that has always been in-place?

Deja vu: same causes behind Datadog’s largest-ever outage

In an unexpected forerunner to this event, Datadog suffered a global outage lasting two days in 2023, which had an apparently identical root cause to that which knocked Heroku offline, last month. From our deepdive into that historic incident at Datadog:

Automatic updates that touch systemd: Ubuntu 22.04 performs an automatic system update. This is the exact same OS version that Heroku uses!

systemd restarts: just like with Heroku, systemd restarts after the update, but the service does not reboot.

Network routes removed: with systemd re-executing itself, systemd-networkd was restarted. Due to the restart, this process inadvertently removed network routes.

Control Plane goes offline: Cilium handles communication between containers. Datadog’s network control plane manages the Kubernetes clusters. Due to the routes being removed, the VMs (nodes) in these routes simply vanished from the network control plane, going offline.

All updates happened at the same time. The problem was these updates happened almost simultaneously, on tens of thousands of virtual machines. This was not even the worst part, losing the network control plane was.

Datadog ran its infrastructure in 5 regions, across 3 different cloud providers, and the Ubuntu update still took the service offline! The outage cost the company $5M. At the time, Datadog took actions:

Ensure systemd restarts don’t degrade its service. Datadog made changes so that upon the systemd update, the routing tables needed for Cilium (the container routing control plane that manages the Kubernetes clusters) are no longer removed.

No more automatic updates. Datadog has disabled the legacy security update channel in the Ubuntu base image, and rolled this change out across all regions. The company now manually rolls out all updates, including security updates, in a controlled fashion.

It’s rare for unconnected incidents to be so similar that they look like cases of “lightning striking twice,” but could this be one of those occasions?

However, it’s unreasonable to expect an engineering team to keep up to date with every single other major outage that ever happened. Even when two outages look the same, the details often differ. And in all fairness, it took Datadog two days to resolve its incident, and more than two months to publish a postmortem, while Heroku had a day of downtime and published its review within five days.

Service down, but status page stays green

An unexpected aspect of this outage was that while Heroku went fully down, its status page showed that everything was working fine. Meanwhile, there were no updates on the @HerokuStatus social media channel until around 8 hours into the outage. What happened?

Well, the outage hit Heroku’s status page infrastructure that also seems to run on Ubuntu 22.04 dynos, with no outbound HTTP requests, and it affected their ability to post to social media. From the postmortem:

[47 minutes into the outage] The Technology team discovered that key Heroku internal incident response tools were affected, including https://status.heroku.com, which could not be updated for customer communication.

[6 hours and 16 minutes into the outage] The Technology team found a workaround to update the public status page on https://status.heroku.com, but it still continued to have intermittent errors when viewed by customers [that is, the status page could still not be updated]

[7 hours and 58 minutes into the outage] The Technology team implemented a capability to enable status posting for the @herokustatus account on X while Salesforce’s status site was inaccessible and posted a status update.

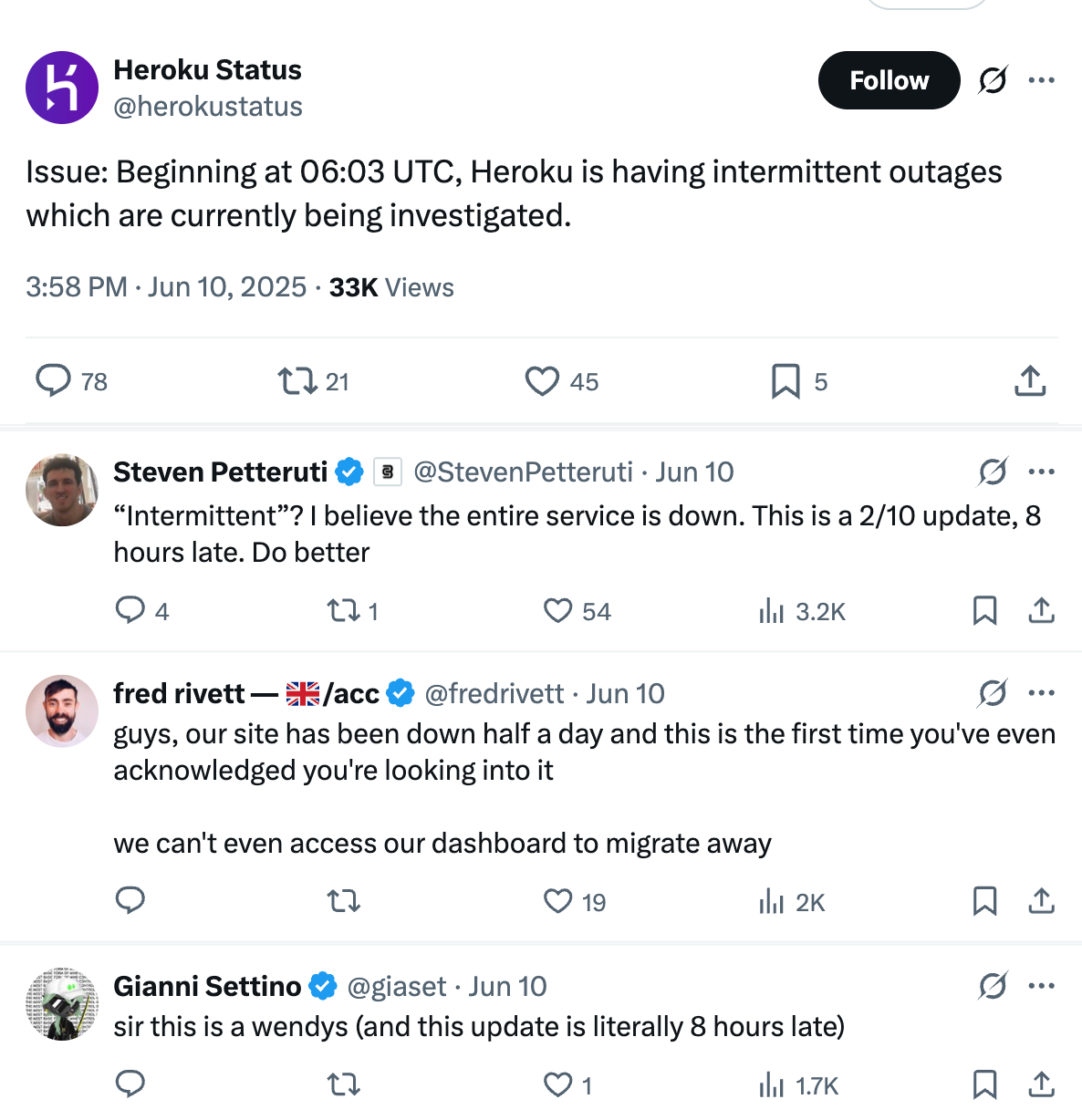

Posting the first status update 8 hours into a global outage was criticized, as might be expected:

The rest of the incident mirrored how long it took Heroku to publicly acknowledge a catastrophic outage: slow to diagnose, slow to mitigate.

Inexplicably long to detect, mitigate & communicate

A real head-scratcher is why it took so long for Heroku to identify the issue and root cause:

One hour into the incident: internally acknowledge it. The engineering team noticed 47 minutes into the outage that they could not use Heroku’s incident response tools, but waited 13 more minutes to investigate.

Spend an hour with a third party. Even though Heroku’s internal outage tooling was down and customers could not use the service, Heroku spent an hour “engaging with a third-party vendor to help troubleshoot suspected networking issues.” It would have been interesting to know who this “third-party” was and why the engineering team waited patiently, instead of doing internal debugging in parallel?

At 2.5 hours: pinpoint the issue. It took two hours, 26 minutes to figure out that “the majority of dynos in Private Spaces were unable to make outbound HTTP requests” aka Heroku stopped working for most customers

At 8.5 hours to find the root cause, and:

3 hours for the engineering team to identify missing network routes

6 hours to learn of an unexpected network service restart

6.5 hours to figure out an OS reboot was the cause

At 11.5 hours to start get the fix ready to stop auto updates

At 13 hours to fix the underlying issue by rolling out the fix to all hosts

At 23 hours: full cleanup of affected services done, and incident mitigated and fully resolved

We know from Datadog that this systemd restart is a hairy issue to pinpoint. It would have been nice to hear more details on how Heroku’s team rallied their team to solve the issue, or did they not do this?

Did Heroku change things after the outage?

The postmortem is light on detail about the incident itself, and feels hand-wavey with its learnings, as well. It’s as if a Comms team went through the report and made sure to share as few details as possible. Here is the complete section on learnings:

“Our post-mortem identified three core areas for improvement.

First, the incident was triggered by unexpected weaknesses in our infrastructure. A lack of sufficient immutability controls allowed an automated process to make unplanned changes to our production environment.

Second, our communication cadence missed the mark during a critical outage, customers needed more timely updates – an issue made worse by the status page being impacted by the incident itself.

Finally, our recovery process took longer than it should have. Tooling and process gaps hampered our engineers’ ability to quickly diagnose and resolve the issue”.

That’s it; a day-long outage – the longest I can recall by Heroku – and this is the sum total of learnings. Obviously, there could be more:

Why did monitoring or alerts not tell the engineering team that Heroku was down, hard?

If monitoring and alerting were also down, this alone should have been an alert!

Is monitoring and alerting running on infra independent of Heroku? If not, why not?

Is Heroku monitoring the right things? What are the monitoring and alerting gaps?

Why was it not an “all hands on deck” situation? The timeline of events suggests one or two oncall engineers doing sequential investigation at a pretty cosy pace: ping a third party to have them investigate… did not work… see if it’s an upstream networking issue… hmm no… let’s disable affected hosts… hmm did not work. These steps took 1-2 hours each.

Why were there no parallel workstreams kicked off?

Why did the team default to waiting on third-parties, instead of conducting their own investigation

Why did it take so long to look at the networking stack at dynos? Is expertise missing from the team?

How does Heroku’s reliability team keep up-to-date with wider industry learnings? This is not about pointing fingers, but one of the most-discussed outages in 2023 was Datdog’s $5M outage that happened thanks to a sytemd restart on an OS update. News of this outage made it wide and far, and some teams took note and turned off automatic OS updates. How does Heroku make sure that their team not only learns from their own mistakes, but from the broader industry? How is the team contributing to industry best-practices, how are they adopting them, and how are they building an organization that is world-class in resilience?

And there’s more; why did Heroku not follow-up on much-needed improvements made a month after this large outage? In the postmortem, the Heroku team makes big promises, such as “building new [incident] tools and improving existing ones”, and “no system changes will occur outside of the controlled deployment process.” The post promises to “provide updates in an upcoming blog post.” But over a month later, there’s no update.

No doubt Heroku’s engineering team is working on improvements, but apparently with the same urgency as they handled the outage.

It’s striking how much Heroku’s focus on reliability seems to have degraded from the outside. I went through several incidents from 2010 (like this or this), and back then Heroku’s engineering team was visibly obsessed with keeping customers in the loop, and improving reliability as they went.

This 2025 incident was the worst in Heroku history: and yet I sense no real urgency coming from the company. Perhaps this is purely perception, and inside the company there’s a huge focus on resilience? If there is: it doesn’t show from the outside!

Or perhaps Heroku is now in maintenance mode, and the product is being prepared to be sunset in a few years’ time? Again, this explanation could as well be true as the previous one. How the team responded during and after this outage suggests this latter scenario is more likely than the former.

Perhaps this is ultimately not a bad thing: large companies which are perceived to become complacent and less customer-focused make space for new, ambitious startups to take their market share. Up-and-coming Heroku competitors from the latest 2025 survey by The Pragmatic Engineer:

It will be interesting to see if Heroku loses customers to more responsive infra companies after this poorly-handled outage, the hand-wavey postmortem, and follow-up work that hadn’t materialized after a month.

2. Google Cloud: globally replicating a config triggers worldwide outage

On 12 June, a good part of Google Cloud went down globally for up to 3 hours. The incident took down many Google Cloud Platform (GCP) services: