Software engineering with LLMs in 2025: reality check

How are devs at AI startups and in Big Tech using AI tools, and what do they think of them? A broad overview of the state of play in tooling, with Anthropic, Google, Amazon, and others

Hi – this is Gergely with the monthly, free issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. If you’ve been forwarded this email, you can subscribe here.

Two weeks ago, I gave a keynote at LDX3 in London, “Software engineering with GenAI.” During the weeks prior, I talked with software engineers at leading AI companies like Anthropic and Cursor, in Big Tech (Google, Amazon), at AI startups, and also with several seasoned software engineers, to get a sense of how teams are using various AI tools, and which trends stand out.

If you have 25 minutes to spare, check out an edited video version, which was just published on my YouTube channel. A big thank you to organizers of the LDX3 conference for the superb video production, and for organizing a standout event – including the live podcast recording (released tomorrow) and a book signing for The Software Engineer’s Guidebook.

This article covers:

Twin extremes. Executives at AI infrastructure companies make bold claims, which developers often find fall spectacularly flat.

AI dev tooling startups. Details from Anthropic, Anysphere, and Codeium, on how their engineers use Claude Code, Cursor, and Windsurf.

Big Tech. How Google and Amazon use the tools, including how the online retail giant is quietly becoming an MCP-first company.

AI startups. Oncall management startup, incident.io, and a biotech AI, share how they experiment with AI tools. Some tools stick and others are disappointments.

Seasoned software engineers. Observations from experienced programmers, Armin Ronacher (creator of Flask), Peter Steinberger (founder of PSPDFKit), Birgitta Böckeler (Distinguished Engineer at Thoughtworks), Simon Willison (creator of Django), Kent Beck (creator of XP), and Martin Fowler (Chief Technologist at Thoughtworks).

Open questions. Why are founders/CEOs more bullish than devs about AI tools, how widespread is usage among developers, how much time do AI tools really save, and more.

The bottom of this article could be cut off in some email clients. Read the full article uninterrupted, online.

1. Twin extremes

There’s no shortage of predictions that LLMs and AI will change software engineering – or that they already have done. Let’s look at the two extremes.

Bull case: AI execs. Headlines about companies with horses in the AI race:

“Anthropic’s CEO said all code will be AI-generated in a year.” (Inc Magazine, March 2025).

“Microsoft's CEO reveals AI writes up to 30% of its code — some projects may have all code written by AI” (Tom’s Hardware, April 2025)

“Google chief scientist predicts AI could perform at the level of a junior coder within a year” (Business Insider, May 2025)

These are statements of confidence and success – and as someone working in tech, the last two might have some software engineers looking over their shoulders, worrying about job security. Still, it’s worth remembering who makes such statements: companies with AI products to sell. Of course they pump up its capabilities.

Bear case: disappointed devs. Two amusing examples about AI tools not exactly living up to the hype: the first from January, when coding tool Devin generated a bug that cost a team $733 in unnecessary costs by generating millions of PostHog analytics events:

While responsibility lies with the developer who accepted a commit without closer inspection, if an AI tool’s output is untrustworthy, then that tool is surely nowhere near to taking software engineers’ work.

Another case enjoyed with self-confessed schadenfreude by those not fully onboard with tech execs’ talk of hyper-productive AI, was the public preview of GitHub Copilot Agent, when the agent kept stumbling in the .NET codebase.

Fumbles included the agent adding tests that failed, with Microsoft software engineers needing to tell the agent to restart:

Microsoft deserves credit for not hiding away the troubles with its agent: the .NET repository has several pull requests opened by the agent which were closed because engineers gave up on getting workable results from the AI.

We cover more on this incident in the deepdive, Microsoft is dogfooding AI dev tools’ future.

So between bullish tech executives and unimpressed developers, what’s the truth? To get more details, I reached out to engineers at various types of companies, asking how they use AI tools now. Here’s what I learned…

2. AI dev tools startups

It’s harder to find more devs using AI tools for work than those at AI tooling companies which build tools for professionals, and dogfood their products.

Anthropic

The Anthropic team told me:

“When we gave Claude Code to our engineers and researchers, they all started using it every day, which was pretty surprising.”

Today, 90% of the code for Claude Code is written by Claude Code(!), Anthropic’s Chief Product Officer Mike Krieger says. And usage has risen sharply since 22 May – the launch day of Claude Sonnet 4 and Claude Code:

40%: how much Claude Code usage increased by on the launch day of Claude Sonnet 4

160%: Userbase growth in the month after launch

These numbers suggest Claude Code and Claude Sonnet 4 are hits among developers. Boris Cherny, creator of Claude Code, said this on the Latent Space podcast:

"Anecdotally for me, it's probably doubled my productivity. I think there are some engineers at Anthropic for whom it's probably 10x-ed their productivity."

MCP (Model Context Protocol) was created by Anthropic in November 2024. This is how it works:

MCP is gaining popularity and adoption across the industry:

November 2024: Anthropic open sources MCP

December 2024 – February 2025: Block, Replit, Windsurf, and Sourcegraph, adopt the protocol

March, April: OpenAI, Google, Microsoft also adopt it

Today: Thousands of active MCP servers operate, and adoption continues

We cover more about the protocol and its importance in MCP Protocol: a new AI dev tools building block.

Windsurf

Asked how they use their own product to build Windsurf, the team told me:

“~95% of our code is written using Windsurf’s agent Cascade and the passive coding feature, Windsurf Tab.”

Some non-engineers at the company also use Windsurf. Gardner Johnson, Head of Partnerships, used it to build his own quoting system, and replace an existing B2B vendor.

We previously covered How Windsurf is built with CEO Varun Mohan.

Cursor

~40-50% of Cursor’s code is written from output generated by Cursor, the engineering team at the dev tools startup estimated, when I asked. While this number is lower than Claude Code and Windsurf’s numbers, it’s still surprisingly high. Naturally, everyone at the company dogfoods Cursor and uses it daily.

We cover more on how Cursor is built in Real-world engineering challenges: building Cursor.

3. Big Tech

After talking with AI dev tools startups, I turned to engineers at Google and Amazon.

Google

From talking with five engineers at the search giant, it seems that when it comes to developer tooling, everything is custom-built internally. For example:

Borg: the Google version of Kubernetes. It predates Kubernetes, which was built by Google engineers, with learnings from Borg itself. We cover more on the history of Kubernetes with Kat Cosgrove.

Cider: the Google version of their IDE. Originally, it started off as a web-based editor. Later, a VS Code fork was created (called Cider-v). Today, this VS Code version is the “main” one and is simply called “Cider.”

Critique: in-house version of GitHub’s code review

Code Search: the internal Sourcegraph, which Code Search predates. Sourcegraph was inspired by Code Search. We previously covered Sourcegraph’s engineering culture.

The reason Google has “custom everything” for its tooling is because the tools are integrated tightly with each other. Among Big Tech, Google has the single best development tooling: everything works with everything else, and thanks to deep integrations, it’s no surprise Google added AI integrations to all of these tools:

Cider:

Multi-line code completion

Chat with LLM inside IDE for prompting

Powered by Gemini

As a current engineer told me: “Cider suggests CL [changelist – Google’s version of pull requests] descriptions, AI input on code reviews, AI auto complete. It has a chat interface like Cursor, but the UX is not as good.”

Critique: AI code review suggestions

CodeSearch: AI also integrated

An engineer told me that Google seems to be taking things “slow and steady” with developer tools:

“Generally, Google is taking a very cautious approach here to build trust. They definitely want to get it right the first time, so that software engineers (SWEs) can trust it.”

Other commonly-used tools:

Gemini: App and Gemini in Workspace features are usually dogfooded internally, and are available with unlimited usage for engineers

LLM prompt playground: works very similarly to OpenAI’s dev playground, and predates it

Internal LLM usage: various Gemini models are available for internal use: big and small, instruction-tuned, and more creative ones, thinking models and experimental ones.

MOMA search engine: knowledge base using LLMs. This is a chatbot fine-tuned with Google’s inside knowledge. The underlying model is based on some version of the Gemini model, but what it provides is pretty basic: answers to direct questions. Devs tell me MOMA is promising, but not as useful as some hoped, likely due to how dependent it is on internal documentation. For example, if a team’s service is badly documented and lacks references, the model wouldn’t do well on questions about it. And since all Google’s services are custom, the generic model knowledge doesn’t help (e.g., details about Kubernetes don’t necessarily apply to Borg!)

NotebookLM: heavily used. One use case is to feed in all product requirement documents / user experience researcher documents, and then ask questions about the contents. NotebookLM is a publicly available product.

Google keeps investing in “internal AI islands.” A current software engineer told me:

“There are many org-specific and team-specific GenAI tooling projects happening everywhere. This is because it’s what leadership likes to see, these days!

Cynically: starting an AI project is partly how you get more funding these days. As to how effective this tooling is, who knows!”

I’d add that Google’s strategy of funding AI initiatives across the org might feel wasteful at first glance, but it’s exactly how successful products like NotebookLM were born. Google has more than enough capacity to fund hundreds of projects, and keep doubling down on those that win traction, or might generate hefty revenue.

Google is preparing for 10x more code to be shipped. A former Google Site Reliability Engineer (SRE) told me:

“What I’m hearing from SRE friends is that they are preparing for 10x the lines of code making their way into production.”

If any company has data on the likely impact of AI tools, it’s Google. 10x as much code generated will likely also mean 10x more:

Code review

Deployments

Feature flags

Source control footprint

… and, perhaps, even bugs and outages, if not handled with care

Amazon

I talked with six current software development engineers (SDEs) at the company for a sense of the tools they use.

Amazon Q Developer is Amazon’s own GitHub Copilot. Every developer has free access to the Pro tier and is strongly incentivized to use it. Amazon leadership and principal engineers at the company keep reminding everyone about it.

What I gather is that this tool was underwhelming at launch around two years ago because it only used Amazon’s in-house model, Nova. Nova was underwhelming, meaning Q was, too.

This April, that changed: Q did away with the Nova dependency and became a lot better. Around half of devs I spoke with now really like the new Q; it works well for AWS-related tasks, and also does better than other models in working with the Amazon codebase. This is because Amazon also trained a few internal LLMs on their own codebase, and Q can use these tailored models. Other impressions:

Limited to files. Amazon Q can currently only understand one file at a time — a limitations SDEs need to work around.

Works well with Java. If Amazon runs on one thing, it’s Java, so this is a great fit.

Finetuned models are only marginally better. Even models trained on Amazon’s own codebase feel only moderately better than non-trained models, surprisingly.

Cline hooked up to Bedrock is a popular alternative: A lot of SDEs prefer to use Cline hooked up to AWS Bedrock where they run a model (usually Sonnet 4)

Q CLI: the command line interface (CLI) is becoming very popular very quickly internally, thanks to this tool using the AWS CLI being able to directly hook up to MCP servers, of which Amazon has hundreds already (discussed below)

Q Transform: used for platform migrations internally, migrating from one language version (e.g. Java 8) to another (e.g. Java 11). It’s still hit-and-miss, said engineers: it works great with some internal services, and not others. Q transform is publicly available.

Amazon Q is a publicly available product and so far, the feedback I’m hearing from non-Amazon devs is mixed: it works better for AWS context, but a frequent complaint is how slow autocomplete is, even for paying customers. Companies paying for Amazon Q Pro are exploring snappier alternatives, like Cursor.

Claude Sonnet is another tool most Amazon SDEs use for any writing-related work. Amazon is a partner to Anthropic, which created these models, and SDEs can access Sonnet models easily – or just spin up their own instance on Bedrock. While devs could also use the more advanced Opus model, I’m told this model has persistent capacity problems – at least at present.

What SDEs are using the models for:

Writing PR/FAQ documents (also called “working backwards” documents). These documents are a big part of the culture, as covered in Inside Amazon’s engineering culture.

Writing performance review feedback for peers, and to generate self-reviews

Writing documentation

…any writing task which feels like a chore!

It’s worth considering what it would mean if more devs used LLMs to generate “mandatory” documents, instead of their own capabilities. Before LLMs, writing was a forcing function of thinking; it’s why Amazon has its culture of “writing things down.” There are cases where LLMs are genuinely helpful, like for self-review, where an LLM can go through PRs and JIRA tickets from the last 6 months to summarize work. But in many cases, LLMs generate a lot more text with much shorter prompts, so will the amount of time spent thinking about problems reduce with LLMs doing the writing?

Amazon to become “MCP-first?”

In 2002, Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos introduced an “API mandate.” As former Amazon engineer Steve Yegge recalled:

“[Jeff Bezos’] Big Mandate went something along these lines:

1. All teams will henceforth expose their data and functionality through service interfaces.

2. Teams must communicate with each other through these interfaces.

3. There will be no other form of interprocess communication allowed: no direct linking, no direct reads of another team's data store, no shared-memory model, no back-doors whatsoever. The only communication allowed is via service interface calls over the network. (...)

6. Anyone who doesn't do this will be fired.

7. Thank you; have a nice day!

Ha, ha! Ex-Amazon folks will of course realize immediately that #7 was a little joke I threw in, because Bezos most definitely does not give a s**t about your day.

#6 was real, so people went to work.”

Since the mid-2000s, Amazon has been an “API-first” company. Every service a team owned offered APIs for any other team to use. Amazon then started to make several of its services available externally, and we can see many of those APIs as today’s AWS services. In 2025, Amazon is a company with thousands of teams, thousands of services, and as many APIs as services.

Turning an API into an MCP server is trivial, which Amazon does at scale. It’s simple for teams that own APIs to turn them into MCP servers, and these MCP servers can be used by devs with their IDEs and agents to get things done. A current SDE told me:

“Most internal tools and websites already added MCP support. This means it’s trivial to hook up automation with an agent and the ticketing agent, email systems, or any other internal service with an API. You can chain pretty much everything!”

Another engineer elaborated:

“There’s even an internal amazon MCP server that hooks into our wiki, ticketing system, and Quip. The internal MCP also works with Q CLI. This integration steadily increased in popularity internally.”

Developers are often selectively lazy, and some have started to automate previously tedious workflows.

Amazon is likely the global leader in adopting MCP servers at scale, and all of this can be traced back to that 2002 mandate from Bezos pushing everyone to build APIs.

4. AI startups

Next, I turned to engineers working at startups building AI products, but not AI developer tools. I was curious about how much cutting-edge companies use LLMs for development.

incident .io

The startup is a platform for oncall, incident response, and status pages, and became AI-first in the past year, given how useful LLMs are in this area. (Note: I’m an investor in the company.)

Software engineer Lawrence Jones said:

“Our team is massively into using AI tools to accelerate them. Over the last couple of years we’ve…

Seen many engineers adopt IDEs like Cursor and use them for both writing code and understanding it

Built Claude Code 'Projects' which contain our engineering documentation, so people can draft code in our style, according to our conventions and architecture preferences

Lots of the team use Granola to track notes from calls, sometimes grabbing a room to just talk to their phone about plans which they’ll later reformat into a doc

Claude Code has been the biggest change, though. Our entire team are regular users. Claude Code is the interactive terminal app that runs an Anthropic agent to explore and modify your codebase.”

The team has a Slack channel where team members share their experience with AI tools for discussion. Lawrence shared a few screenshots of the types of learnings shared:

The startup feels like it’s in heavy experimentation mode with tools. Sharing learnings internally surely helps devs get a better feel for what works and what doesn’t.

Biotech AI startup

One startup asked not to be named because no AI tools have “stuck” for them just yet, and they’re not alone. But there’s pressure to not appear “anti-AI”, especially as theirs is a LLM-based business.

The company builds ML and AI models to design proteins, and much of the work is around building numerical and automated ML pipelines. The business is doing great, and has raised multiple rounds of funding, thanks to a product gaining traction within biology laboratories. The company employs a few dozen software engineers.

The team uses very few AI coding tools. Around half of devs use Vim or Helix as editors. The rest use VS Code or PyCharm – plus the “usual” Python tooling like Jupyter Notebooks. Tools like Cursor are not currently used by engineers, though they were trialled.

The company rolled out an AI code review tool, but found that 90% of AI comments were unhelpful. Despite the other 10% being good, the feedback felt too noisy. Here’s how an engineer at the company summarized things:

“We've experimented with several options with LLMs, but little has really stuck.

It's still faster to just write correct code than to review LLM code and fix its problems, even using the latest models.

Given the hype around LLMs, I speculate that we might just be in a weird niche.”

An interesting detail emerged when I asked how they would compare the impact of AI tools to other innovations in the field. This engineer said that for their domain, the impact of the uv project manager and ruff linter has been greater than AI tools, since uv made their development experience visibly faster!

Ruff is 10-100x faster than existing Python linters. Moving to this linter created a noticeable developer productivity gain for the biotech AI startup

It might be interesting to compare the impact of AI tools to other recent tools like ruff/uv. These have had a far greater impact.

This startup is a reminder that AI tools are not one-size-fits-all. The company is in an unusual niche where ML pipelines are far more common than at most companies, so the software they write will feel more atypical than at a “traditional” software company.

The startup keeps experimenting with anything that looks promising for developer productivity: they’ve found moving to high-performance Python libraries is a lot more impactful than using the latest AI tools and models; for now, that is!

5. Seasoned software engineers

Finally, I turned to a group of accomplished software engineers, who have been in the industry for years, and were considered standout tech professionals before AI tools started to spread.

Armin Ronacher: from skeptic to believer

Armin is the creator of Flask, a popular Python library, and was the first engineering hire at application monitoring scaleup, Sentry. He has been a developer professionally for 17 years, and was pretty unconvinced by AI tooling, until very recently. Then, a month ago he published a blog post, AI changes everything:

“If you would have told me even just six months ago that I'd prefer being an engineering lead to a virtual programmer intern over hitting the keys myself, I would not have believed it. I can go and make a coffee, and progress still happens. I can be at the playground with my youngest while work continues in the background. Even as I'm writing this blog post, Claude is doing some refactorings.”

I asked what changed his mind about the usefulness of these tools.

“A few things changed in the last few months:

Claude Code got shockingly good. Not just in the quality of the code, but in how much I trust it. I used to be scared of giving it all permissions, now it's an acceptable risk to me – with some hand holding.

I learned more. I learned from others, and learned myself, about how to get it to make productivity gains

Clearing the hurdle of not accepting it, by using LLMs extensively. I was very skeptical; in particular, my usage of Cursor and similar code completion actually went down for a while because I was dissatisfied. The agentic flow, on the other hand, went from being not useful at all, to indispensable.

Agents change the game. Tool usage, custom tool usage, and agents writing their own tools to iterate, are massive game changers. The faults of the models are almost entirely avoided because they can run the code and see what happens. With Sonnet 3.7 and 4, I noticed a significant step up in the ability to use tools, even if the tools are previously unknown or agent created.”

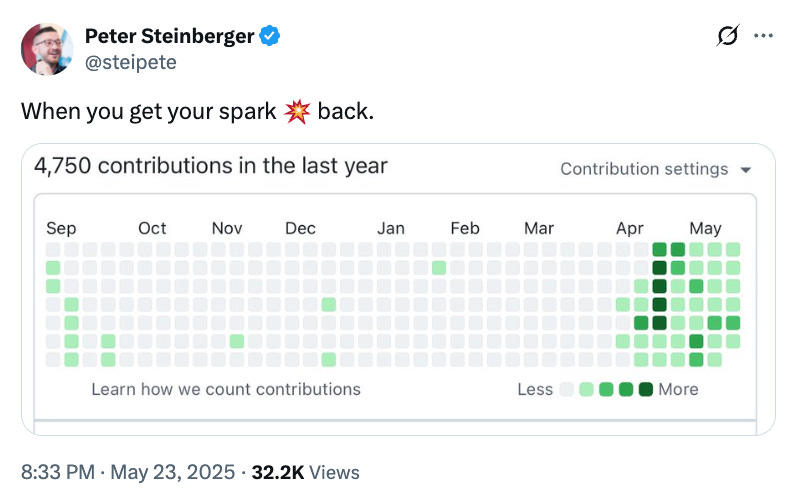

Peter Steinberger: rediscovering a spark for creation

Peter Steinberger has been an iOS and Mac developer for 17 years, and is founder of PSPDFKit. In 2021, he sold all his shares in the company when PSPDFKit raised €100M in funding. He then started to tinker with building small projects on the side. Exactly one month ago, he published the post The spark returns. He writes:

“Right now, we are at an incredible crossroads in technology. AI is moving so fast and is changing the way we work in software development, but furthermore, it’s going to change the world. I haven’t been as excited, astounded, and amazed by any technology in a very long time.”

Indeed, something major did change for Pete: for the first time in ages he started to code regularly.

I asked what the trigger was that got him back to daily coding. Peter’s response:

“Tools got better. Models reached a stage where they are really capable, pricing went down: we're at this inflection point where suddenly things "just work", and especially with Cursor and Claude Code they became easy. Everyone can just open that thing on their project, type in what they want and it just happens.

I see more and more folks getting infected by it. Once they see how capable this new generation of tools is, it doesn't take long before their excitement is through the roof. These tools fundamentally change how we build software.

Suddenly, every side project is just a few sentences away, code becomes cheap, languages and frameworks matter less because it got incredibly simple to just switch. Combine that power with a capable engineer, and you easily create 10-20x the output.

I see people left and right quitting their jobs to dedicate all their time to AI. My friend just said "it's the most exciting time since I started to learn programming”. Suddenly, I feel I can build anything I want.”

Pete emphasized:

“I’m telling you, [agentic AI tools] are the biggest shift, ever. Been talking to a bunch of engineers who wanna quit their job just because they wanna go all in on doing stuff with AI!”

Birgitta Böckeler: a new “lateral move” in development

Birgitta is a Distinguished Engineer at Thoughtworks, and has been writing code for 20 years. She has been experimenting with and researching GenAI tools for the last two years, and last week published Learnings from two years of using AI tools for software engineering in The Pragmatic Engineer. Talking with me, she summarized the state of GenAI tooling:

“We should embrace that GenAI is a lateral move and opportunity for something new, not a continuation of how we've abstracted and automated, previously. We now have this new tool that allows us to specify things in an unstructured way, and we can use it on any abstraction level. We can create low code applications with it, framework code, even Assembly.

I find this lateral move much more exciting than thinking of natural language as "yet another abstraction level". LLMs open up a totally new way in from the side, which brings so many new opportunities.”

Simon Willison: “coding agents” actually work now

Simon has been a developer for 25 years, is the creator of Django, and works as an independent software engineer. He writes an interesting tech blog, documenting learnings from working with LLMs, daily. He was also the first-ever guest on The Pragmatic Engineer Podcast in AI tools for software engineers, but without the hype. I asked how he sees the current state of GenAI tools used for software development:

“Coding agents are a thing that actually work now: run an LLM in a loop, let it execute compilers and tests and linters and other tools, give it a goal, and watch it do the work for you. The models’ improvement in the last six months have tipped them over from fun toy demos, to being useful on a daily basis.”

Kent Beck: Having more fun than ever

Kent Beck is the creator of Extreme Programming (XP), an early advocate of Test Driven Development (TDD), and co-author of the Agile Manifesto. In a recent podcast episode he said:

“I’m having more fun programming than I ever had in 52 years.”

AI agents revitalized Kent, who says he feels he can take on more ambitious projects, and worry less about mastering the syntax of the latest framework being used. I asked if he’s seen other “step changes” for software engineering in the 50 years of his career, as what LLMs seem to provide. He said he has:

“I saw similar changes, impact-wise:

Microprocessors (1970s): the shift from mainframe computing

The internet (2000s): changed the digital economy

iPhone and Android (2010s): suddenly things like live location sharing is possible, and the percentage of time spent online sharply increased”

Martin Fowler: LLMs are a new nature of abstraction

Martin Fowler is Chief Scientist at Thoughworks, author of the book Refactoring, and a co-author of the Agile Manifesto. This is what he told me about LLMs:

“I think the appearance of LLMs will change software development to a similar degree as the change from assembler to the first high-level programming languages did.

The further development of languages and frameworks increased our abstraction level and productivity, but didn't have that kind of impact on the nature of programming.

LLMs are making the same degree of impact as high-level languages made versus the assembler. The distinction is that LLMs are not just raising the level of abstraction, but also forcing us to consider what it means to program with non-deterministic tools.”

Martin expands on his thoughts in the article, LLMs bring a new nature of abstraction.

6. Open questions

There are plenty of success stories in Big Tech, AI startups, and from veteran software engineers, about using AI tools for development. But many questions also remain, including:

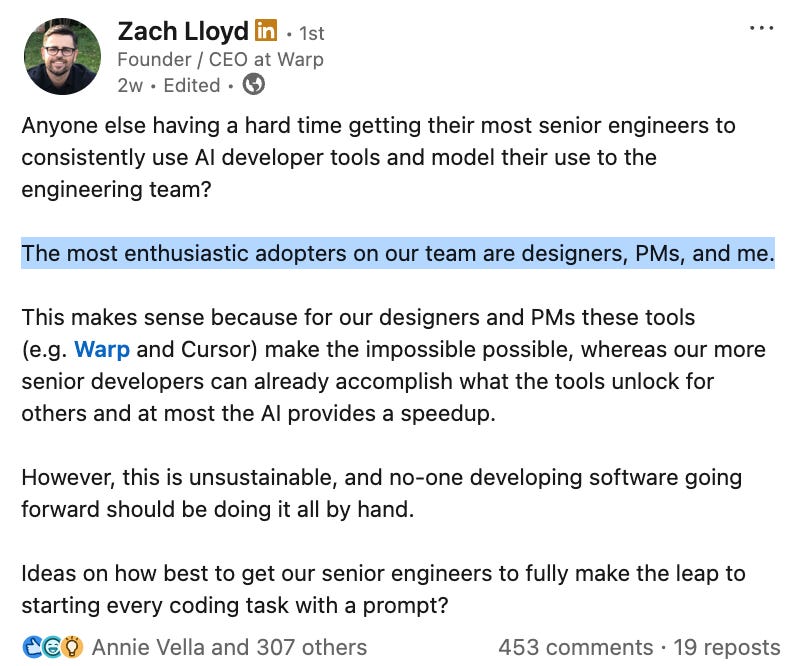

#1: Why are founders and CEOs much more excited?

Founders and CEOs seem to be far more convinced of the breakthrough nature of AI tools for coding, than software engineers are. One software engineer-turned-founder and executive who runs Warp, an AI-powered command line startup, posted for help in convincing devs to stop dragging their feet on adopting LLMs for building software:

#2: How much do devs use AI?

Developer intelligence platform startup DX recently ran a study with 38,000 participants. It’s still not published, but I got access to it (note: I’m an investor at DX, and advise them). They asked developers whether they use AI tools at least once a week:

5 out of 10 devs use AI tools weekly across all companies (50%)

6 out of 10 devs use them weekly at “top” companies (62%)

On one hand, that is incredible adoption. GitHub Copilot launched with general availability 3 years ago, and Cursor launched just 2 years ago. For 50% of all developers to use AI-powered dev tools in such a short time feels like faster adoption than any tool has achieved, to date.

On the other hand, half of devs don’t even use these new tools once a week. It’s safe to assume many devs gave them a try, but decided against them, or their employer hasn’t invested.

#3: How much time does AI save devs, really?

In the same study, DX asked participants to estimate how much time these tools saved for them. On the median, it’s around 4 hours per week:

Is four hours lots? It’s 10% of a 40-hour workweek, which is certainly meaningful. But it is nowhere near the amounts reported in the media: like Sam Altman’s claim that AI could make engineers 10x as productive.

Google CEO Sundar Pichai also estimated that the company is seeing 10% productivity increase thanks to AI tools on a Lex Fridman podcast episode, which roughly matches the DX study.

This number feels grounded to me: devs don’t spend all their time coding, after all! There’s a lot of thinking and talking with others, admin work, code reviews, and much else to do.

#4: Why don’t AI tools work so great for orgs?

Laura Tacho, CTO at DX told me:

“These GenAI tools are great for the individual developer right now, but not yet that good at the organizational level.”

This observation makes sense: increasing coding output will not lead to faster software production, automatically; not without increasing code review throughout, deployment frequency, doing more testing (as more code likely means more bugs), and adapting the whole “software development pipeline” to make use of faster coding.

Plus, there’s the issue that some things simply take time: planning, testing, gathering feedback from users and customers, etc. Even if code is generated in milliseconds, other real-world constraints don’t just vanish.

#5: Lack of buzz among devs

I left this question to last: why do many developers not believe in LLMs’ usefulness, before they try it out? It’s likely to do with the theory that LLMs are less useful in practice, then they theoretically should be.

Simon Willison has an interesting observation, which he shared on the podcast:

“Right now, if you start with the theory, it will hold you back. With LLMs, it's weirdly harmful to spend too much time trying to understand how they actually work, before you start playing with them, which is very unintuitive.

I have friends who say that if you're a machine learning researcher, if you've been training models and stuff for years, you're actually more disadvantaged when starting to use these tools, than if you come in completely fresh! That’s because LLMs are very weird; they don't react like you expect from other machine learning models.”

Takeaways

Summarizing the different groups which use LLMs for development, there’s surprising contributions from each:

I’m not too surprised about the first three groups:

AI dev tools startups: their existence depends on selling tools to devs, so it’s only natural they’d “eat their own dogfood”

Big Tech: companies like Google and Amazon are very profitable and want to protect their technology advantage, so will invest heavily in any technology that could disrupt them, and incentivize engineers to use these tools; especially home grown ones, like Google’s Gemini and Amazon’s Q.

AI startups: these are innovative companies, so it’s little surprise they experiment with AI dev tools. I found it refreshing to talk to a startup where the new tools don’t work that well, yet.

The last one is where I pay a lot more attention. For seasoned software engineers: most of these folks had doubts, and were sceptical about AI tools until very recently. Now, most are surprisingly enthusiastic, and see AI dev tools as a step change that will reshape how we do software development.

LLMs are a new tool for building software that us engineers should become hands-on with. There seems to have been a breakthrough with AI agents like Claude Code in the last few months. Agents that can now “use” the command line to get feedback about suggested changes: and thanks to this addition, they have become much more capable than their predecessors.

As Kent Beck put it in our conversation:

“The whole landscape of what's ‘cheap’ and what's ‘expensive’ has shifted.

Things that we didn't do because we assumed they were expensive or hard, just got ridiculously cheap.

So, we just have to be trying stuff!”

It’s time to experiment! If there is one takeaway, it would be to try out tools like Claude Code/OpenAI Codex/Amp/Gemini CLI/Amazon Q CLI (with AWS CLI integration), editors like Cursor/Windsurf/VS Code with Copilot, other tools like Cline, Aider, Zed – and indeed anything that looks interesting. We’re in for exciting times, as a new category of tools are built that will be as commonplace in a few years as using a visual IDE, or utilizing Git as a source control, is today.

Did you come across conflicting opinions from seasoned software engineers when writing this article?

For instance, this piece by Glyph [1] to which Armin Ronacher responded to in his blog [2].

[1] https://blog.glyph.im/2025/06/i-think-im-done-thinking-about-genai-for-now.html

[2] https://lucumr.pocoo.org/2025/6/10/genai-criticism/

Richard Hamming's Book - The Art of Science and Engineering - is a great study for how doing one part of the system better (coding, but now with AI) could produce more solutions on the surface and more problems in the system. If more code is being output, other tools (ex. reviews) have to keep up with the inevitable issues that show up with stronger output from one part of the system.

The real question is does the overall system improve with these tools by a high amount or is it marginal?