The AI Engineering Stack

Three layers of the AI stack, how AI engineering is different from ML engineering and fullstack engineering, and more. An excerpt from the book AI Engineering by Chip Huyen

“AI Engineering” is a term that I didn’t hear about two years ago, but today, AI engineers are in high demand. Companies like Meta, Google, and Amazon, offer higher base salaries for these roles than “regular” software engineers get, while AI startups and scaleups are scrambling to hire them.

However, closer inspection reveals AI engineers are often regular software engineers who have mastered the basics of large language models (LLM), such as working with them and integrating them.

So far, the best book I’ve found on this hot topic is AI Engineering by Chip Huyen, published in January by O’Reilly. Chip has worked as a researcher at Netflix, was a core developer at NVIDIA (building NeMo, NVIDIA’s GenAI framework), and cofounded Claypot AI. She has also taught machine learning (ML) at Stanford University.

In February, we published a podcast episode with Chip about what AI engineering is, how it differs from ML engineering, and the techniques AI engineers should be familiar with.

For this article, I asked Chip if she would be willing to share an excerpt of her book, and she has generously agreed. This covers what an AI engineering stack looks like: the one us software engineers must become expert in order to be an AI engineer.

In today’s issue we get into:

Three layers of the AI stack. Application development, model development, infrastructure.

AI engineering versus ML engineering. Similarities and differences, including how inference optimization evaluation matters more in AI engineering, and ML knowledge being more of a nice-to-have and less of a must-have.

Application development in AI engineering. The three main focus areas: evaluation, prompt engineering, and AI interfaces.

AI Engineering versus full-stack engineering. “AI engineering is just software engineering with AI models thrown in the stack.”

If you find this excerpt useful, you’ll likely get value from the rest of the book, which can be purchased as an ebook or a physical copy. This newsletter has also published some deepdives which you may find useful for getting into AI engineering:

AI Engineering in the real world – stories from 7 software engineers-turned AI engineers

Building, launching, and scaling ChatGPT Images – insights from OpenAI’s engineering team

Building Windsurf – and the engineering challenges behind it

As with all recommendations in this newsletter, I have not been paid to mention this book, and no links in this article are affiliates. For more details, see my ethics statement.

With that, let’s get into it:

This excerpt is from Chapter 1 of AI Engineering, by Chip Huyen. Copyright © 2025 Chip Huyen. Published by O'Reilly Media, Inc. Used with permission.

AI engineering’s rapid growth has induced an incredible amount of hype and FOMO (fear of missing out). The number of new tools, techniques, models, and applications introduced every day can be overwhelming. Instead of trying to keep up with these constantly shifting sands, let’s inspect the fundamental building blocks of AI engineering.

To understand AI engineering, it’s important to recognize that AI engineering evolved out of ML engineering. When a company starts experimenting with foundation models, it’s natural that its existing ML team should lead the effort. Some companies treat AI engineering the same as ML engineering, as shown in Figure 1-12.

Some companies have separate job descriptions for AI engineering, as shown in Figure 1-13.

Regardless of where organizations position AI engineers and ML engineers, their roles significantly overlap. Existing ML engineers can add AI engineering to their list of skills to enhance their job prospects, and there are also AI engineers with no ML experience.

To best understand AI engineering and how it differs from traditional ML engineering, the following section breaks down the different layers of the AI application building process, and looks at the role each layer plays in AI and ML engineering.

1. Three layers of the AI Stack

There are three layers to any AI application stack: application development, model development, and infrastructure. When developing an AI application, you’ll likely start from the top layer and move downwards as needed:

Application development

With models so readily available, anyone can use them to develop applications. This is the layer that has seen the most action in the last two years, and it’s still rapidly evolving. Application development involves providing a model with good prompts and necessary context. This layer requires rigorous evaluation and good applications demand good interfaces.

Model development

This layer provides tooling for developing models, including frameworks for modeling, training, fine-tuning, and inference optimization. Because data is central to model development, this layer also contains dataset engineering. Model development also requires rigorous evaluation.

Infrastructure

At the bottom of the stack is infrastructure, which includes tooling for model serving, managing data and compute, and monitoring.

The three layers, and examples of responsibilities for each one, are shown below:

To get a sense of how the landscape has evolved with foundation models; in March 2024, I searched GitHub for all AI-related repositories with at least 500 stars. Given the prevalence of GitHub, I believe this data is a good proxy for understanding the ecosystem. In my analysis, I also included repositories for applications and models, which are the products of the application development and model development layers, respectively. I found a total of 920 repositories. Figure 1-15 shows the cumulative number of repositories in each category month by month.

The data shows a big jump in the number of AI toolings in 2023, after the introduction of Stable Diffusion and ChatGPT. That year, the categories which saw the biggest increases were applications and application development. The infrastructure layer saw some growth, but much less than in other layers. This is expected: even though models and applications have changed, the core infrastructural needs of resource management, serving, monitoring, etc., remain the same.

This brings us to the next point. While the level of excitement and creativity around foundation models is unprecedented, many principles of building AI applications are unchanged. For enterprise use cases, AI applications still need to solve business problems, and, therefore, it’s still essential to map from business metrics to ML metrics, and vice versa, and you still need to do systematic experimentation. With classical ML engineering, you experiment with different hyperparameters. With foundation models, you experiment with different models, prompts, retrieval algorithms, sampling variables, and more. We still want to make models run faster and cheaper. It’s still important to set up a feedback loop so we can iteratively improve our applications with production data.

This means that much of what ML engineers have learned and shared over the last decade is still applicable. This collective experience makes it easier for everyone to begin building AI applications. However, built on top of these enduring principles are many innovations unique to AI engineering.

2. AI engineering versus ML engineering

While the unchanging principles of deploying AI applications are reassuring, it’s also important to understand how things have changed. This is helpful for teams that want to adapt their existing platforms for new AI use cases, and for developers interested in which skills to learn in order to stay competitive in a new market.

At a high level, building applications using foundation models today differs from traditional ML engineering in three major ways:

Without foundation models, you have to train your own models for applications. With AI engineering, you use a model someone else has trained. This means AI engineering focuses less on modeling and training, and more on model adaptation.

AI engineering works with models that are bigger, consume more compute resources, and incur higher latency than traditional ML engineering. This means there’s more pressure for efficient training and inference optimization. A corollary of compute-intensive models is that many companies now need more GPUs and work with bigger compute clusters than previously, which means there’s more need for engineers who know how to work with GPUs and big clusters [A head of AI at a Fortune 500 company told me his team knows how to work with 10 GPUs, but not how to work with 1,000 GPUs.]

AI engineering works with models that can produce open-ended outputs, which provide models with the flexibility for more tasks, but are also harder to evaluate. This makes evaluation a much bigger problem in AI engineering.

In short, AI engineering differs from ML engineering in that it’s less about model development, and more about adapting and evaluating models. I’ve mentioned model adaptation several times, so before we move on, I want to ensure we’re on the same page about what “model adaptation” means. In general, model adaptation techniques can be divided into two categories, depending on whether they require updating model weights:

Prompt-based techniques, which includes prompt engineering, adapt a model without updating the model weights. You adapt a model by giving it instructions and context, instead of changing the model itself. Prompt engineering is easier to get started on and requires less data. Many successful applications have been built with just prompt engineering. Its ease of use allows you to experiment with more models, which increases the chance of finding a model that is unexpectedly good for an application. However, prompt engineering might not be enough for complex tasks, or applications with strict performance requirements.

Fine-tuning, on the other hand, requires updating model weights. You adapt a model by making changes to the model itself. In general, fine-tuning techniques are more complicated and require more data, but they can significantly improve a model’s quality, latency, and cost. Many things aren’t possible without changing model weights, such as adapting a model to a new task it wasn’t exposed to during training.

Now, let’s zoom into the application development and model development layers to see how each has changed with AI engineering, starting with what ML engineers are more familiar with. This section gives an overview of different processes involved in developing an AI application.

Model development

Model development is the layer most commonly associated with traditional ML engineering. It has three main responsibilities: modeling and training, dataset engineering, and inference optimization. Evaluation is also required because most people come across it first in the application development layer.

Modeling and training

Modeling and training refers to the process of coming up with a model architecture, training it, and fine-tuning it. Examples of tools in this category are Google’s TensorFlow, Hugging Face’s Transformers, and Meta’s PyTorch.

Developing ML models requires specialized ML knowledge. It requires knowing different types of ML algorithms such as clustering, logistic regression, decision trees, and collaborative filtering, and also neural network architectures such as feedforward, recurrent, convolutional, and transformer. It also requires understanding of how a model learns, including concepts such as gradient descent, loss function, regularization, etc.

With the availability of foundation models, ML knowledge is no longer a must-have for building AI applications. I’ve met many wonderful, successful AI application builders who aren’t at all interested in learning about gradient descent. However, ML knowledge is still extremely valuable, as it expands the set of tools you can use, and helps with trouble-shooting when a model doesn’t work as expected.

Differences between training, pre-training, fine-tuning, and post-training

Training always involves changing model weights, but not all changes to model weights constitute training. For example, quantization, the process of reducing the precision of model weights, technically changes the model’s weight values but isn’t considered training.

The term “training” can often be used in place of pre-training, finetuning, and post-training, which refer to different phases:

Pre-training refers to training a model from scratch; the model weights are randomly initialized. For LLMs, pre-training often involves training a model for text completion. Out of all training steps, pre-training is often the most resource-intensive by a long shot. For the InstructGPT model, pre-training takes up to 98% of the overall compute and data resources. Pre-training also takes a long time. A small mistake during pre-training can incur a significant financial loss and set back a project significantly. Due to the resource-intensive nature of pre-training, it has become an art that only a few practice. Those with expertise in pre-training large models, however, are highly sought after [and attract incredible compensation packages].

Fine-tuning means continuing to train a previously-trained model; model weights are obtained from the previous training process. Since a model already has certain knowledge from pre-training, fine-tuning typically requires fewer resources like data and compute than pre-training does.

Post-training. Many people use post-training to refer to the process of training a model after the pre-training phase. Conceptually, post-training and fine-tuning are the same and can be used interchangeably. However, sometimes, people use them differently to signify the different goals. It’s usually post-training when done by model developers. For example, OpenAI might post-train a model to make it better at following instructions before releasing it.

It’s fine-tuning when it’s done by application developers. For example, you might fine-tune an OpenAI model which has been post-trained in order to adapt it to your needs.

Pre-training and post-training make up a spectrum, and their processes and toolings are very similar.

[Footnote: If you think the terms “pre-training” and “post-training” lack imagination, you’re not alone. The AI research community is great at many things, but naming isn’t one of them. We already talked about how “large language model” is hardly a scientific term because of the ambiguity of the word “large”. And I really wish people would stop publishing papers with the title “X is all you need.”]

Some people use “training” to refer to prompt engineering, which isn’t correct. I read a Business Insider article in which the author said she’d trained ChatGPT to mimic her younger self. She did so by feeding her childhood journal entries into ChatGPT. Colloquially, the author’s usage of the “training” is correct, as she’s teaching the model to do something. But technically, if you teach a model what to do via the context input into it, then that is prompt engineering. Similarly, I’ve seen people use “fine-tuning” to describe prompt engineering.

Dataset engineering

Dataset engineering refers to curating, generating, and annotating data needed for training and adapting AI models.

In traditional ML engineering, most use cases are close-ended: a model’s output can only be among predefined values. For example, spam classification with only two possible outputs of “spam” and “not spam”, is close-ended. Foundation models, however, are open-ended. Annotating open-ended queries is much harder than annotating close-ended queries; it’s easier to determine whether an email is spam than it is to write an essay. So data annotation is a much bigger challenge for AI engineering.

Another difference is that traditional ML engineering works more with tabular data, whereas foundation models work with unstructured data. In AI engineering, data manipulation is more about deduplication, tokenization, context retrieval, and quality control, including removing sensitive information and toxic data.

Many people argue that because models are now commodities, data is the main differentiator, making dataset engineering more important than ever. How much data you need depends on the adapter technique you use. Training a model from scratch generally requires more data than fine-tuning does, which in turn requires more data than prompt engineering.

Regardless of how much data you need, expertise in data is useful when examining a model, as its training data gives important clues about its strengths and weaknesses.

Inference optimization

Inference optimization means making models faster and cheaper. Inference optimization has always been important for ML engineering. Users never reject faster models, and companies can always benefit from cheaper inference. However, as foundation models scale up to incur ever-higher inference cost and latency, inference optimization has become even more important.

One challenge of foundation models is that they are often autoregressive: tokens are generated sequentially. If it takes 10ms for a model to generate a token, it’ll take a second to generate an output of 100 tokens, and even more for longer outputs. As users are notoriously impatient, getting AI applications’ latency down to the 100ms latency expected of a typical internet application is a huge challenge. Inference optimization has become an active subfield in both industry and academia.

A summary of how the importance of categories of model development changes with AI engineering:

3. Application development in AI engineering

With traditional ML engineering where teams build applications using their proprietary models, the model quality is a differentiation. With foundation models, where many teams use the same model, differentiation must be gained through the application development process.

The application development layer consists of these responsibilities: evaluation, prompt engineering, and AI interface.

Evaluation

Evaluation is about mitigating risks and uncovering opportunities, and is necessary throughout the whole model adaptation process. Evaluation is needed to select models, benchmark progress, determine whether an application is ready for deployment, and to detect issues and opportunities for improvement in production.

While evaluation has always been important in ML engineering, it’s even more important with foundation models, for many reasons. To summarize, these challenges arise chiefly from foundation models’ open-ended nature and expanded capabilities. For example, in close-ended ML tasks like fraud detection, there are usually expected ground truths which you can compare a model’s outputs against. If output differs from expected output, you know the model is wrong. For a task like chatbots, there are so many possible responses to each prompt that it is impossible to curate an exhaustive list of ground truths to compare a model’s response to.

The existence of so many adaptation techniques also makes evaluation harder. A system that performs poorly with one technique might perform much better with another. When Google launched Gemini in December 2023, they claimed Gemini was better than ChatGPT in the MMLU benchmark (Hendrycks et al., 2020). Google had evaluated Gemini using a prompt engineering technique called CoT@32. In this technique, Gemini was shown 32 examples, while ChatGPT was shown only 5 examples. When both were shown five examples, ChatGPT performed better, as shown below:

Prompt engineering and context construction

Prompt engineering is about getting AI models to express desirable behaviors from the input alone, without changing the model weights. The Gemini evaluation story highlights the impact of prompt engineering on model performance. By using a different prompt engineering technique, Gemini Ultra’s performance on MMLU went from 83.7% to 90.04%.

It’s possible to get a model to do amazing things with just prompts. The right instructions can get a model to perform a task you want in the format of your choice. Prompt engineering is not just about telling a model what to do. It’s also about giving the model the necessary context and tools for a given task. For complex tasks with long context, you might also need to provide the model with a memory management system, so the model can keep track of its history.

AI interface

AI interface means creating an interface for end users to interact with AI applications. Before foundation models, only organizations with sufficient resources to develop AI models could develop AI applications. These applications were often embedded into organizations’ existing products. For example, fraud detection was embedded into Stripe, Venmo, and PayPal. Recommender systems were part of social networks and media apps like Netflix, TikTok, and Spotify.

With foundation models, anyone can build AI applications. You can serve your AI applications as standalone products, or embed them into other products, including products developed by others. For example, ChatGPT and Perplexity are standalone products, whereas GitHub’s Copilot is commonly used as a plug-in in VSCode, while Grammarly is commonly used as a browser extension for Google Docs. Midjourney can be used via its standalone web app, or its integration in Discord.

There needs to be tools that provide interfaces for standalone AI applications, or which make it easy to integrate AI into existing products. Here are some interfaces that are gaining popularity for AI applications:

Standalone web, desktop, and mobile apps. [Streamlit, Gradio, and Plotly Dash are common tools for building AI web apps.]

Browser extensions that let users quickly query AI models while browsing.

Chatbots integrated into chat apps like Slack, Discord, WeChat, and WhatsApp.

Many products, including VSCode, Shopify, and Microsoft 365, provide APIs that let developers integrate AI into their products as plug-ins and add-ons. These APIs can also be used by AI agents to interact with the world.

While the chat interface is the most commonly used, AI interfaces can also be voice-based, such as voice assistants, or they can be embodied as with augmented and virtual reality.

These new AI interfaces also mean new ways to collect and extract user feedback. The conversation interface makes it so much easier for users to give feedback in natural language, but this feedback is harder to extract.

A summary of how the importance of different categories of app development changes with AI engineering:

4. AI Engineering versus full-stack engineering

The increased emphasis on application development, especially on interfaces, brings AI engineering closer to full-stack development. [Footnote: 7 Anton Bacaj told me: “AI engineering is just software engineering with AI models thrown in the stack.”]

The growing importance of interfaces leads to a shift in the design of AI toolings to attract more frontend engineers. Traditionally, ML engineering is Python-centric. Before foundation models, the most popular ML frameworks supported mostly Python APIs. Today, Python is still popular, but there is also increasing support for JavaScript APIs, with LangChain.js, Transformers.js, OpenAI’s Node library, and Vercel’s AI SDK.

While many AI engineers come from traditional ML backgrounds, more increasingly come from web development or full-stack backgrounds. An advantage that full-stack engineers have over traditional ML engineers is their ability to quickly turn ideas into demos, get feedback, and iterate.

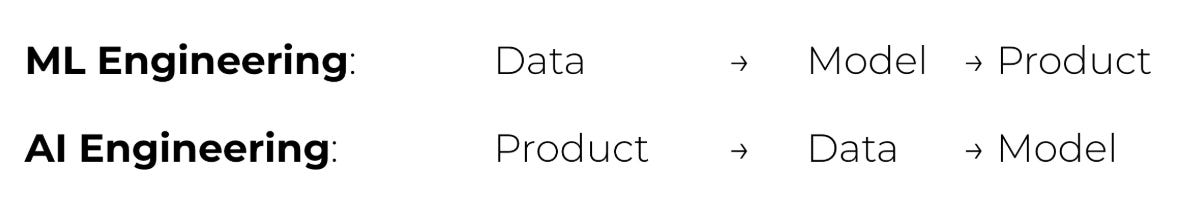

With traditional ML engineering, you usually start with gathering data and training a model. Building the product comes last. However, with AI models readily available today, it’s possible to start with building the product first, and only invest in data and models once the product shows promise, as visualized in Figure 1-16.

In traditional ML engineering, model development and product development are often disjointed processes, with ML engineers rarely involved in product decisions at many organizations. However, with foundation models, AI engineers tend to be much more involved in building the product.

Summary

I intend this chapter to serve two purposes. One is to explain the emergence of AI engineering as a discipline, thanks to the availability of foundation models. The second is to give an overview of the process of building applications on top of these models. I hope this chapter achieves this. As an overview, it only lightly touches on many concepts, which are explored further in the book.

The rapid growth of AI engineering is motivated by the many applications enabled by the emerging capabilities of foundation models. We’ve covered some of the most successful application patterns, for both consumers and enterprises. Despite the incredible number of AI applications already in production, we’re still in the early stages of AI engineering, with countless more innovations yet to be built.

While AI engineering is a new term, it has evolved out of ML engineering, which is the overarching discipline involved in building applications with all ML models. Many principles of ML engineering are applicable to AI engineering. However, AI engineering also brings new challenges and solutions.

One aspect of AI engineering that is challenging to capture in words is the incredible collective energy, creativity, and engineering talent of the community. This enthusiasm can often be overwhelming, as it’s impossible to keep up-to-date with new techniques, discoveries, and engineering feats that seem to happen constantly.

One consolation is that since AI is great at information aggregation, it can help us aggregate and summarize all these new updates! But tools can help only to a certain extent; the more overwhelming a space is, the more important it is to have a framework to help navigate it. This book aims to provide such a framework.

The rest of the book explores this framework step-by-step, starting with the fundamental building block of AI engineering: foundation models that make so many amazing applications possible.

Gergely, again. Thanks, Chip, for sharing this excerpt. To go deeper in this topic, consider picking up her book, AI Engineering, in which many topics mentioned in this article are covered in greater depth, including:

Sampling variables are discussed in Chapter 2

Pre-training and post-training differences are explored further in Chapters 2 and 7

The challenges of evaluating foundation models are discussed in Chapter 3

Chapter 5 discusses prompt engineering, and Chapter 6 discusses context construction

Inference optimization techniques, including quantization, distillation, and parallelism, are discussed in Chapters 7 through 9

Dataset engineering is the focus of Chapter 8

User feedback design is discussed in Chapter 10

“AI Engineering” is surprisingly easy for software engineers to pick up. When LLMs went mainstream in late 2022, I briefly assumed that to work in the AI field, one needed to be an ML researcher. This is still true if you want to work in areas like foundational model research. However, most AI engineering positions at startups, scaleups and Big Tech, are about building AI applications on top of AI APIs, or self-hosted LLMs.

Most of the complexity lies in the building of applications, not the LLM model part. That’s not to say there are not a bunch of new things to learn in order to become a standout AI engineer, but it’s still very much doable, and many engineers are making the switch.

I hope you enjoyed this summary of the AI engineering stack. For more deepdives on AI engineering, check out:

AI Engineering in the real world – Hands-on examples and learnings from software engineers turned “AI engineers” at seven companies

Building, launching, and scaling ChatGPT Images – ChatGPT Images became one of the largest AI engineering projects in the world, overnight. But how was it built? A deepdive with OpenAI’s engineering team

Building Windsurf – the engineering challenges of building an AI product serving hundreds of billions of tokens per day.

AI Engineering with Chip Huyen – What is AI engineering, and how to get started with it? Podcast with Chip.

Great chapter, demystifies so much. I've added the book to my read queue.

Despite the fact that I already own the book, I definitely prefer "original" articles here, whether they're written by Gergely or some guest author.