The Trimodal Nature of Tech Compensation Revisited

Why can a similar position offer 2-4x more in compensation, in the same market? A closer look at the trimodal model I published in 2021. More data, and new observations.

👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a subscriber-only issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. To get articles like this in your inbox, every week, subscribe:

This article is part of a 3-part series on trimodal compensation:

Part 1: The trimodal nature of software engineering salaries in the Netherlands and Europe (2021)

Part 2: The trimodal nature of tech compensation revisited (2024, this article)

Part 3: The trimodal nature of tech compensation in the US, UK and India (2025)

My most frequently-cited article to date is one published before the Pragmatic Engineer newsletter had even launched. It’s The trimodal nature of software engineering salaries in the Netherlands and Europe. I wrote it in 2021, between leaving my role as an engineering manager at Uber and starting this newsletter.

The article attempted to analyze how tech compensation really works, mainly in the Netherlands. I wrote it because I was confused by the very large differences in compensation figures quoted in tech salary research about pay for senior software engineers, and what Uber actually offered tech professionals in Amsterdam. There was an invisible comp range which nobody talked about and I wanted to find out if this gap was real. And if so: why did it exist?

I based my analysis on 4 years I’d spent as a hiring manager; extending offers, learning about counter-offers, and candidates sharing their comp numbers. It also included around 100 data points from the Netherlands market which I sourced via a form I asked people to share their pay details in.

Three years later, I have comp feedback from hundreds of tech professionals, have spent a load of time talking with hiring managers, CTOs, and founders about pay, and also amassed 10x more data points. So, it’s time for a fresh look at the model!

Today, we cover:

The trimodal model. A summary of the three tiers of the model, and how I detected it while researching the gap between public compensation benchmarks and the ranges I saw as a hiring manager.

Applicability in the US, Canada, UK, Europe, etc. Over the last three years, I’ve received plenty of feedback on the model and it’s proved surprisingly accurate in describing tech compensation structures globally..

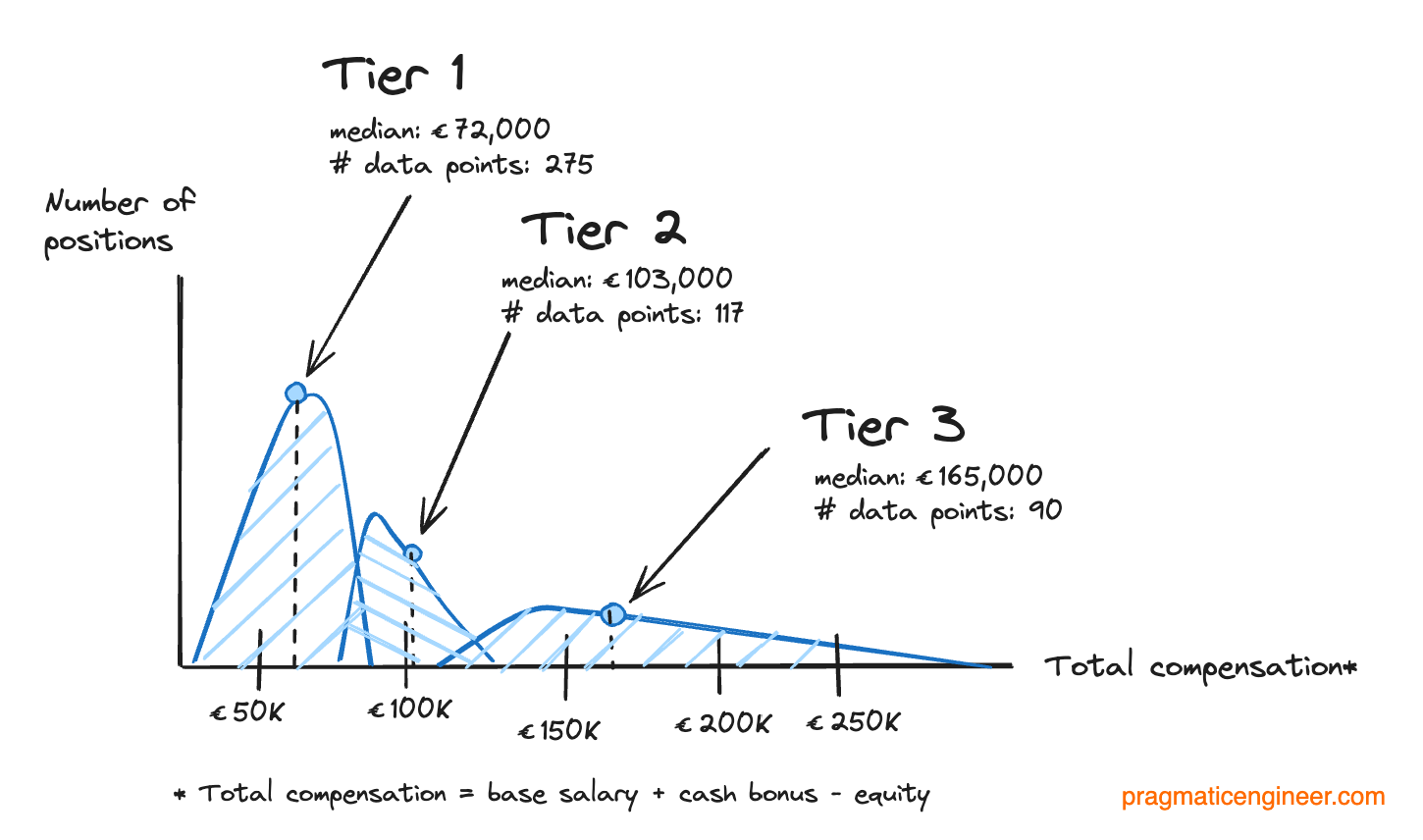

Validating the trimodal model with data. I parsed more than 1,000 data points, and manually tagged the company’s tier. Then looked at the distribution with this tagging: which distribution validated the correctness of the trimodal assumption.

Compensation numbers and tier distribution — in the Netherlands. Compensation data points for seniors, staff+, engineering managers and engineering executives. The lowest tier (Tier 1) seems to include the majority of total positions, with the fewest being in the highest tier (Tier 3.) The differences between tiers can help inform what to expect on other markets.

Top-paying (tier 3) companies and mid-paying (Tier 2) ones. Most of Big Tech, hedge funds, and some standout VC-funded scaleups are Tier 3, while VC-funded startups and scaleups, most full-remote companies, and plenty of bootstrapped ones tend to be Tier 2. Pointers to how to locate these kinds of companies.

Top-tier realities. Tiers 2 and 3 don’t really contain many differences in expectations, culture, and workload. Both often operate with a Silicon Valley-like engineering culture and are usually more stressful places to work than tier 1 places.

Beyond compensation. Pay is one of the few quantifiable things that are comparable across all jobs. But much of what makes a job “good” is harder to quantify.

We will go into details – with data – about why this kind of distribution for compensation exists in most markets:

This article harnesses data from several previous issues of this newsletter. You won’t be surprised that I recommend them as useful extra context:

Senior-and-above compensation: an overview of senior+ compensation at the 50th, 75th and 90th percentile across global tech markets. A benchmark for getting a sense of pay differences in your region, versus the US, UK or EU.

Compensation at publicly traded tech companies: a good place to identify which public companies may be top tier (3.)

A closer look at top-tier (3) compensation structures: details of Meta and Pinterest.

A closer look at mid-tier (2) compensation structures: details of Wise and (now-defunct) Pollen.

1. The trimodal model

In this article, we discuss total compensation, not just base salary. Total compensation consists of:

Salary: Monthly / bi-weekly compensation, dependent upon country. Most companies in the US, Canada, Australia and Latin America issue paychecks twice a month, while in most of Europe and Asia it’s once a month.

Cash bonus: Usually paid annually, although some companies do it twice a year. Bonus amounts aren’t guaranteed and often depend on a company’s or employee’s performance, or both. A cash bonus is also known as a “profit share” and is rarely revealed before issuance.

Equity. At publicly traded companies, equity is restricted stock units (RSUs) which can be sold after vesting. For privately-owned startups and scaleups, it’s usually double-trigger RSUs, options, phantom shares, SARs (stock appreciation rights,) or more exotic things like growth shares. For more detail, check out Equity 101 for software engineers. Note, almost always it’s only VC-funded startups and publicly traded companies which offer equity.

Back in 2021, I collected around 100 data points on the Dutch market of small local companies, all the way to international businesses like Booking.com, Databricks, Uber, and more. I mapped out the numbers and plotted a line on the graph:

This graph was not what I expected, which was something closer to normal distribution. ‘Normal distribution’ (aka Gaussian distribution) is a common concept in statistics, mapping the probability distribution of a random variable. If we know median total compensation is $X, a normal distribution graph looks something like this:

Normal distribution doesn’t inevitably occur, but experience shows that it frequently describes things containing some degree of randomness, such as human height, blood pressure, exam scores, IQ scores, reaction times – even shoe sizes.

Could this compensation graph be a collection of three other distinct graphs? I noticed three “local maximum” spots:

But what if the graph was not one distribution, but three distinct ones? That would explain the strange shape, and the three local maximums. I grouped the data points behind the graphs, and sure enough, found three different groups:

Local companies (Tier 1): most local businesses that benchmark to the numbers on most salary comparison sites. They usually offer close to – and sometimes slightly above – what government positions advertise for senior engineering roles.

Ambitious local companies (Tier 2): startups, scaleups, and more ambitious local companies that want to hire and retain the best people, locally.

Companies benchmarking across a region (Tier 3). Big Tech companies, hedge funds and scaleups that hire across regions, frequently hire from abroad, and often compete with fellow Big Tech giants for talent.

Mapping these three groups separately to the same data I plotted before, produced this:

This graph looked pretty sensible, and the three distributions more normal. These were still not “normal” distributions, but the “long tails”of tiers 2 and 3 compensation components were explained by equity appreciation. Specifically, outlier data points (very high total compensation numbers) were almost all people who received an equity grant which had appreciated 5-10x since issuance, pushing up total compensation.

The trimodal model explained why public salary benchmarks seemed wrong. It was puzzling that sites like Payscale, Honeypot, and similar sites published median compensation numbers that seemed too low, and did not even hint at the higher packages that clearly exist at the market. The trimodal model explained what was happening: all these sites were only showcasing data for the lowest tier, Tier 1 — and perhaps a few data points for Tier 2. Looking at my model, this checked out:

Comparing data within the Netherlands, it all checked out. Sites like Honeypot and Talent.io reported the median senior software engineering salary was around €60,000/year ($65,000) and they were right: for Tier 1 packages only! I also observed it was possible to find a few more data points in the Tier 2 range scattered among individual data points on sites like Glassdoor, but that there was little public data on Tier 3 – the “invisible” range.

There seem several reasons why there’s so little data on Tier 3.

Relatively few compensation packages, which means sites that look at median, average, or even the 75th percentile, exclude them.

Top earners have little incentive to share their numbers; they know they’re well above publicly reported median numbers.

Many compensation sites do not capture equity in compensation packages. This is because the majority of compensation packages do not have equity (Tier 3 packages are a minority in all markets!), so most sites have not added support to capture this component. And yet, equity is usually the biggest reason for the difference in compensation. But to know this, a site needs to capture equity details!

But in the past few years more data has been published about the top of the market. Salary sharing and offer negotiation site Levels.fyi is the best-known source, covering virtually all top-tier (Tier 3) companies in the US. In Europe, this article lists top tier companies across various European cities. Other sources include Blind, an anonymous social network used by many working in tech, where people are expected to share their total compensation – aka TC – in each post, and some Reddit forums.

Confident that I had sufficient data points for the Netherlands, I published this graph and accompanying article.

2. Applicability in the US, Canada, UK, Europe, and beyond

At the time I didn’t know if the model applied beyond the Netherlands because all data I’d sourced related to that country. The lowlands nation has characteristics that overlap with the US, European countries, and other places with venture-funded tech companies:

US Big Tech is growing. Amazon is expanding its AWS organization in the Netherlands, as is Google Cloud with GCP. Meta also started hiring locally from 2021, and Uber has its European headquarters there.

VC-funded companies with headquarters elsewhere. Plenty of tech companies hiring in the Netherlands are headquartered in the US, UK, and other European countries, and hire heavily in the Netherlands. Examples include Databricks, Stripe, Personio, Fonoa, Linear.

Hedge funds. Few cities in the world have hedge funds and high frequency trading funds hiring software engineers in large numbers. London and New York are the best-known locations, along with Amsterdam. Companies like Optiver, Flow Traders and IMC Trading hire there.

Local VC-funded companies. Mollie (a Stripe competitor valued at $6.5B,) Messagebird (a Twilio competitor valued at $1B,) and Adyen (another Stripe competitor, publicly traded, with a market cap of $35B) are companies founded in the Netherlands that raised venture capital.

The bulk of software engineers are still hired by “local” companies. My sense is that most developer hiring happens this way.

Other countries share these characteristics to varying degrees.

The model seems to hold up well, internationally. Since publication, feedback has been continuous, and hiring managers and engineers confirm the model explains the dynamics in their countries and regions – with only the numbers needing adjustment.

I’ve talked with founders and hiring managers in the US, Canada, UK and EU, who shared that this model is relevant to them.

US:

“I think the Trimodal nature of salaries will apply to the U.S., as well. No data, it's anecdotal, but it's what I have seen in my own experience and in conversations with IC's and managers across all three types of companies.” – VP of engineering Rick Luevanos

“Ignore the absolute numbers if you aren’t in Europe. The trends are the same in the US. I left the first category and moved into the second category last year.” – a software engineer in a post on Reddit

“Moved to Ireland from northern California and have been interested (and delighted) to see SV companies pushing up salaries here. Trimodal salary matches my experiences closely.” – a software engineer in the US

In an interesting follow-up, compensation negotiation and salary benchmarking site Levels.fyi found the model perfectly explains US internship salary ranges:

Canada:

“This is exactly what I experienced in Canada. Tier 1 category companies are the most prevalent and the pay is subpar. I've 2.5x [increased] my salary over the past couple years by getting into Tier 3.” – a software engineer in a post on Reddit

“In general, most Canadian companies are just competing with other Canadian companies and they get away with paying very little. This often changes when they get big and have to start hiring in the US as well (Slack, Shopify, etc.) But this doesn't really change the local market very much.

This is changing slowly with remote work. Big US companies are starting to hire more in Canada because they're getting the same performance for like 75% of the salary. But things are still in flux. Most Canadian companies are still competing with each other and not with the US firms, so you have to jump jobs in order to get that pay raise.

In your terms you're changing "brackets", but really, you're changing "tiers". You're moving from a low paying tier to a higher one.” – a senior principal engineer on Glassdoor

UK: based on data I collected on TechPays, for the UK, the trimodal split describes the UK market well. Compensation packages are higher than in the Netherlands in all tiers by about 15-30%.

New Zealand:

“Slightly different reasons, but I'm seeing something similar in New Zealand. Domestic companies benchmark against each other, and pay lower salaries. Meanwhile Australian companies have mostly come to terms with remote work after the lockdowns, which makes NZ a valuable recruitment market.

And since they benchmark against each other and because NZ is so small, close, and similar, Australian firms mostly don't adjust their salary bands from (higher) Australian norms, so they pay 25-30% more for comparable roles than a domestic NZ company would. Meanwhile, a few American companies are also starting to recruit, and again, most don't adjust their salary bands, and so generally pay 50-80% more than domestic NZ companies.” – a software engineer in a comment on Hacker News.

Japan: software engineer Patrick McKenzie (resident in Japan) suspects the same applies there:

I created this model to explain compensation for engineers and engineering managers, but it seems to hold for product managers, and roles across tech. Aakash Gupta — who writes the publication Product Growth — was a VP of Product and worked at Apollo.io, Affirm, and Epic Games. He concluded:

“If you can get a job at the right company, you can earn 3-5x local companies.

I find the [trimodal] distribution applies to most jobs: engineering, PM, tech, non-tech.”

3. Validating the trimodal model with data

After publishing the model, I launched a side project called TechPays, a site where people can anonymously submit compensation numbers. It’s geared mainly towards Europe, where there are fewer data points for higher tiers. I analyzed detailed data points submitted in 2022. In that year, there were 1,100 submissions for the Netherlands, and 482 were for senior software engineer positions; nearly 10x more data than in the original model.

So, how does the model hold up with the additional data? Cutting out distant outlier data points at the bottom and top, it did pretty well. Here is the 482 data points for senior software engineers with no grouping:

Let’s plot these data points into a line:

I manually tagged each company with the tier that was most appropriate:

Here’s what happens when applying the trimodal model after tagging each company by tier:

Let’s clean the chart up by removing distracting lines and numbers:

As we’ve built up this model from the ground up, using data, we got to a very similar graph to what I hand-drew in 2021. The model seems to hold up: now backed with data.

4. Numbers and tier distribution in the Netherlands

Here are more detailed data points for mid-level, senior, staff+, engineering manager and engineering executives in the Netherlands: