The Product-Minded Engineer: The importance of good errors and warnings

Product engineers are more in demand than ever, but how do you become one? New book, “The Product-Minded Engineer”, offers a guide. An interview with its author and an exclusive excerpt

Before we start: I’m hiring!

The Pragmatic Engineer is not a typical publication, and so this is also not a typical role. I’m looking for someone to help research and compile Tuesday deepdives like the one on Cursor, on Claude Code, on Stripe, and many others. This position will include directly talking with engineers at interesting companies, researching both public details and details made exclusively available to us, and compiling what we learned into detailed reports.

If you’ve worked at startups or Big Tech for a while, would enjoy working full-remote, keeping up with the cutting edge of the industry sounds interesting, and you’d enjoy doing something that can start as part-time: read more and apply here. Applications close Monday, 26 Jan.

One trend in tech is that more startups are hiring for “product engineers” or “product-minded engineers”, who can implement products and also come up with strong product and feature ideas, then build them. This trend of engineers’ involvement from the ideas stage through to shipping looks set to accelerate with AI tools generating ever more code.

My recent analysis of what happens when AI writes almost all the code mentioned that nimble startups were already recruiting “product engineers” who can create their own work, and act as blends of mini-product manager and software engineer. I said this indicates that being more product-minded could become a baseline at startups because it’s increasingly important to specify what an AI tool should build.

But how do you get better at being a product engineer?

Obviously, pairing with a product manager, staying close to the business, and finding a mentor who’s a great product engineer are strong options. But if these aren’t all available in your workplace, there’s now a book dedicated to the topic.

Entitled “The Product-Minded Engineer”, it’s written by former software engineer and current product manager, Drew Hoskins, and published by O’Reilly:

A few years ago, I published an article named “The Product-Minded Software Engineer” which offers tips for software engineers to grow their “product muscle”, and it’s timely that a fellow engineer has invested in writing a guide about this increasingly pertinent subject.

After hearing Drew was working on his book, I got in touch, reviewed a draft version, and asked if he’d consider sharing an excerpt in this newsletter. Graciously, both Drew and O’Reilly agreed. Drew will also be a speaker at The Pragmatic Summit in San Francisco next month, on 11 February, discussing tactics for leading product engineering teams in an AI-native environment.

In today’s issue, we cover:

Author’s background. Twenty years as a software engineer at Microsoft, Facebook, and Stripe – and today as a product manager at Temporal.

Writing the book. Why create this guide now?

Importance of good errors and warnings at product-level. Excerpt from Chapter 3: “Errors and Warnings”, about why designing the right approach to errors has a massive impact upon products used by developers and nontechnical users, too.

My usual disclaimer: as with all my recommendations, I was not paid for this article, and none of the links are affiliates. See my ethics statement for more.

1. Author’s background

With experienced tech professionals who cross over into being published writers, I find it’s always useful to understand something about their background, and Drew has an impressive one spanning more than two decades:

Microsoft: Software Development Engineer (2002–2009). Worked on the C++ compiler backend, static analysis tools, and the Windows UI developer framework.

Facebook: platform/product infra engineer (2009–2015). Worked on the Facebook API and the initial version of the Facebook App Center. Then founded and led a product infrastructure team building the core data APIs for internal engineers. Still used pervasively today, EntSchema turbocharged Facebook’s Ent framework with codegen, reflection, and a sandbox experience. This later led to the popular open-source Ent framework in Go.

Oculus: Software engineer, E7: Senior Staff-level engineer, (2015-2017) Led the effort to rebuild Oculus’s web platform to Facebook’s infrastructure, after the social media giant acquired Oculus. Tech lead for Oculus’ Platform SDK.

Stripe: Staff+ software engineer (2018–2023). Tech Lead on the Stripe Connect product, then founded and led the Workflow Engine, a framework built on Temporal.

Temporal: Staff Product Manager (2024–present). Product manager at Temporal, an open source durable execution workflow service, working on developer experience and agentic orchestration.

Drew went from working on APIs and platform teams, to leading large engineering efforts, and starting new teams and initiatives in his workplaces – before heading over to the “dark side” of product management at a developer tools company. To me, Drew seems the ideal professional to write such a book because he has plentiful experience of working as a software engineer when it was required to understand the business, and he’s now a product manager working with fellow engineers on Temporal.

2. Writing the book

Drew told me more context about this project:

What was the trigger to start writing this book?

“I had written a book outline on usable API design for O’Reilly, and the main themes were product-thinking and user empathy; topics I’ve long wished more engineers engaged with. But Louise Corrigan at O’Reilly liked those themes more than the API topic, and suggested I make product-thinking itself the subject of the book.

I liked how this pivot mirrors my personal career journey; of my interest in API design blossoming into a broader interest in products and users”.

How long did it take to write?

“It was an 18-month process end-to-end, starting the day after I joined Temporal – so that was an intense period! I upgraded a lot of three-day weekends to four-day weekends, and also did some writing on cruise ships. I wrote the whole thing myself, but used friends, and especially Claude, for research. I also sought lots of Alpha and Beta feedback because I believe “it takes a village”. The two biggest inputs were my own career experience and concepts from the design and product communities. It’s well-known stuff, but nobody bothered to inform engineers about it”.

Who’s the best product-minded engineer you worked with?

“John Carmack, with whom I overlapped at Oculus. He’s amazing because he’s super-deep technically in areas like graphics, yet doggedly pursues the most important product goals.

One year, he decided the community needed to level up in building performant VR apps for a mobile compute envelope, so he mentored the entire community in marathon sessions. Another time, he decided the Oculus platform needed more great apps, so went to Netflix and Mojang, worked with those teams, and heroically brought the Netflix and Minecraft VR apps into existence”.

What’s your advice for mid and senior-level software engineers who want to be more product-minded?

“My suggestions:

Ask “why” a lot. Don’t expect to always get clear answers, not even from EMs and PMs.

Switch your viewpoint. Go from the system level, to the user lens, and then back again.

Use scenarios. Simulate and sequence user interactions until this becomes routine. Writing scenario tests is often a good start.

Customer support. Spend time on user support and think about more permanent fixes while you engage and unblock users”.

As a product manager, what can devs do to be seen as product-minded and be invited to do more product work?

“I try to have devs help me author use cases/scenarios. I also invite them to come along on customer calls if they want. If they have an idea, I ask them to justify it with scenarios. If they start throwing use cases back at me without prompting after a couple of months, I know they’re on the journey”.

What is one technique for using AI tools that you’d recommend devs try, in order to be more product-minded?

“It’s easier than ever to gather user signal with AI tools. My team at Temporal has a Claude Code skill for gathering customer signal: the tool searches our internal Slack, community Slack, Miro Insights, GitHub issues, and Gong, and aggregates it all into a report with lots of links to chase down customers and requests. Many of those tools in turn have AI assistants that make all this much easier to do!”

3. Excerpt: “The importance of good errors and warnings at product-level”

The excerpt below is from “The Product-Minded Engineer”, by Drew Hoskins. Copyright © 2025 Drew Hoskins. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc. Used with permission.

From Chapter 3: “Errors and Warnings”

The Value of Diagnostics

Crafting well-structured diagnostics with useful messages is an incredibly valuable and high-leverage way to spend your time. For many applications and platforms with complex and open-ended inputs, diagnostics are the primary interface—the vast majority of the user’s time will be spent dealing with errors and progressing to the next one.

Filling out electronic forms is all about being told about your missing or malformed input. My coding time is at least half dealing with errors and lint rules. Even writing in a word processor has become a constant process of looking at underlined text and being asked to proofread or rephrase.

And yet, as we design software, because errors often don’t appear in screenshots, marketing materials, or API method listings, they can be out of sight and out of mind.

Autonomous agents shine a bright light on this problem. They are now regularly presented with error messages resulting from their actions and instructed to correct their mistakes based on them. If the message isn’t sufficiently helpful, they fail at their task. The process of trying different things is slow and costly. Because agents are billed based on usage, the costs are directly measured.

Tip: Diagnostics may be the most important interface of your product.

Scenarios for Diagnostics

When considering errors, warnings, and their associated messages, it is essential to think about a broad range of scenarios, starting with identifying edge cases, to understanding how developers can automate reactions, and how end users will understand and act upon them. Improve your ability to understand your users’ knowledge, generate user stories, and simulate user interactions, and you’ll improve your diagnostics. For users, we provide contextual and actionable errors. For developers, we carefully select our error types, codes, and metadata so that those who receive them can recover gracefully.

In the rest of this chapter, you’ll learn how to craft refreshingly useful warnings and errors. We’ll explore how to:

Understand the scenario—the persona who will benefit from the error and their situation

Provide enough context to our users for them to understand the error

Provide actionable error messages that suggest what to do about the problem

Choose error codes and types carefully to allow upstream developers to serve their users

Raise errors at the API or UI layer so that messages can be written with full context about what the user’s trying to do

Shift left; that is, fire errors as early as possible to speed up your users, and before bad things happen

In Chapter 8, I’ll address how to list out edge cases to figure out what errors to check for in the first place. For now, I’ll focus on crafting errors once you already know what they are.

Categorizing Error Scenarios

When writing errors, you need to make a few main choices. First, a user-facing choice:

What is the error message?

There are also choices of concern to developers so that they can catch errors and automate responses:

What is the error’s class or code?

What metadata is needed to pinpoint the problem?

Thus, when you craft errors in virtually any application or platform, you must think of two categories of user scenarios: the human one and the programmer one.

There are further divisions in the developer scenarios: are you communicating with members of your team who work on your codebase, or those from other teams or companies? This is especially important if you are building an API or service where upstream developers can catch your error and act upon it.

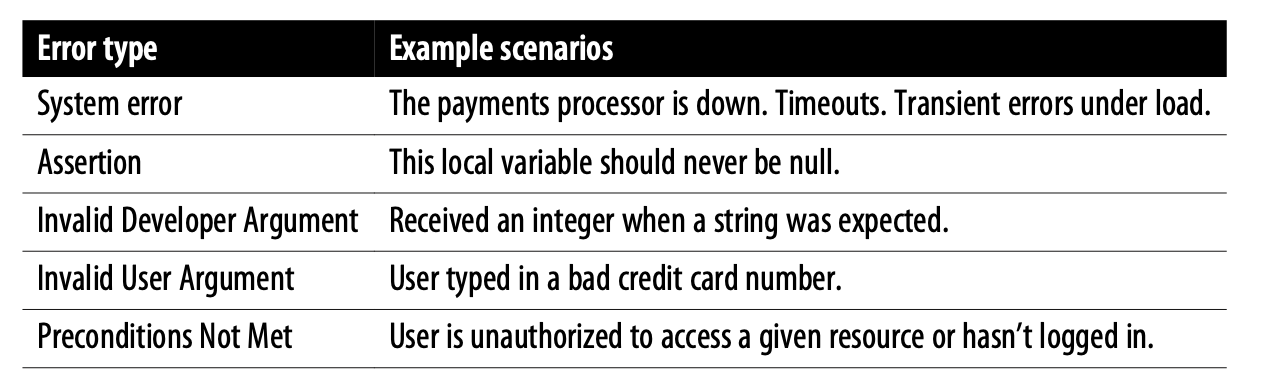

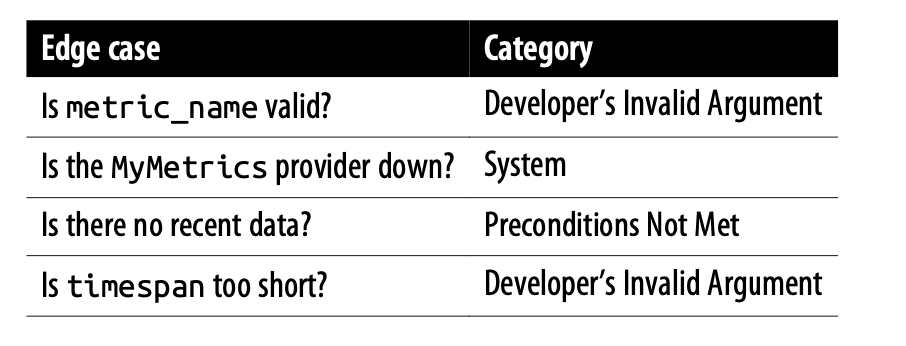

So, the first step is to pitch your message to the right person in the right circumstance. We’ve all seen errors that didn’t seem to be meant for us, such as when websites show code listings to end users. To determine your audience, start by deciding your error’s category. For our purposes, the five shown in Table 3-1 cover most cases.

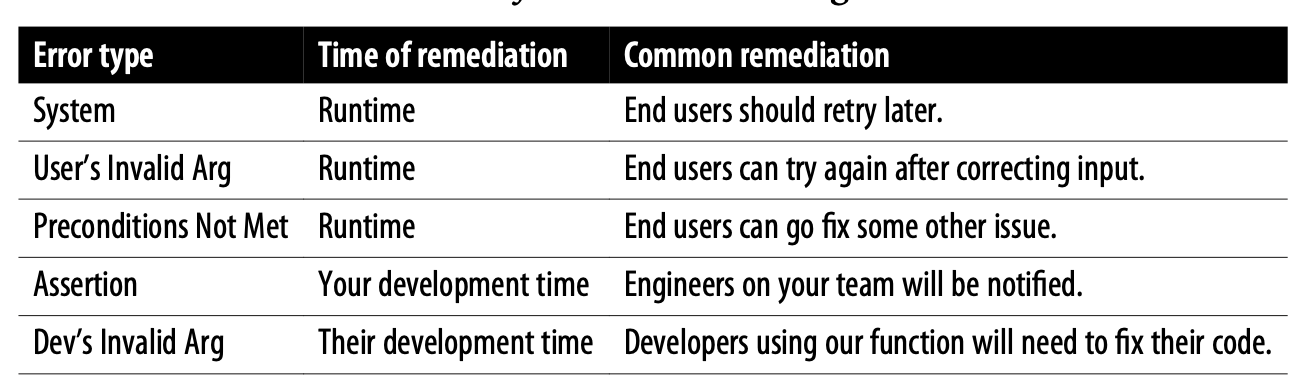

Start by mentally categorizing any error you write. This gives a huge clue as to who you’re talking to—your own team, other developers, or users—and when the errors can be fixed—at runtime or during development. This will help you write with the right vocabulary and suggest helpful actions (see Table 3-2).

These five types of scenarios reveal drastically different strategies. For example, if an assertion triggers in production, it’s usually catastrophic. If the code is in a state the authors didn’t foresee, it will lead to unpredictable behavior—most likely in the form of a crash or a poor error message. Occasionally there are worse consequences, like data corruption. In some programming languages, assertions are stripped out in production to optimize their execution, meaning that you shouldn’t rely on them for anything load bearing. In no case is the end user persona expected to interact with them successfully.

For some applications, all end users are not the same; in which case, messages should be tailored to each persona. A classic example is a Preconditions Not Met error caused by the user not having the necessary access. Is the user an administrator or an end user? This determines whether we will provide them with direct instructions or instruct them to contact an administrator.

Knowing your personas will help you speak to the user’s ontology. (Ontology was defined in Chapter 2 as a structured graph of known concepts.) Consider “PC Load Letter,” [a reference to a segment before this excerpt] which tried to ask users to reload the printer’s paper tray. It was actionable—it told the user to load the paper—but it failed because it was speaking to the wrong persona. “PC” stood for “paper cassette” and “Letter” referred to a size of paper— 8.5”x11”. Perhaps instead, they should have labeled the paper trays A, B, and C and said, “Reload tray B.”

Categorizing Errors in Practice

Let’s work an example to show how to use product thinking to categorize errors.

Which of the five categories does a divide-by-zero—in Python, a ZeroDivisionError —fall into?

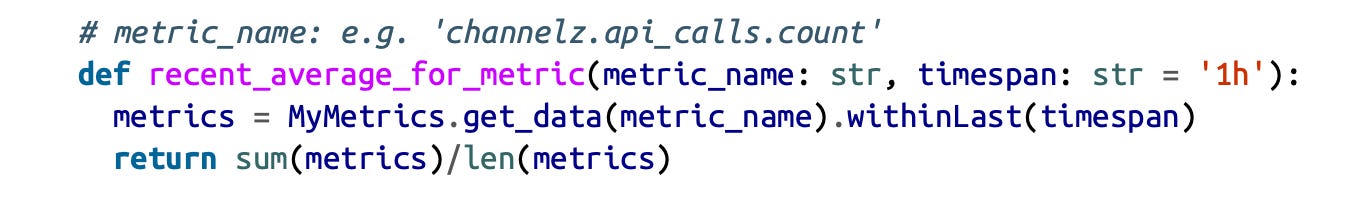

Imagine you are writing a method to compute the average value of an online metric over a time window.

Look at the return statement. If this method threw a ZeroDivisionError when the metrics array was empty, callers would be quite confused—they’d need to know the innards of your function to understand.

Tip: Users and developers should never have to understand your implementation to understand an error.

Thus, unless your code is literally a calculator, a divide-by-zero error is an Assertion, designed to be found at test time and telling your team that the code needs improvement. Avoid it—do some upfront validation before attempting the division.

So, we’re going to validate, but what scenario category would that validation fall under? The circumstance that led to the len(metrics)==0 condition could have been any of those listed in Table 3-3.

As I’ll discuss in the next section on messages, you’ll want to suggest different actions in each of these cases and therefore will need distinguishing checks in the code. Further, you will need to perform these validations at a moment when you have the necessary context.

In this section, we categorized diagnostics as either interacting with developers or end users and distinguished between scenarios that were actionable at runtime and those that were actionable only during development. Next, we’ll build on this to author awesome messages.

Warning and Error Messages

Writing diagnostic messages combines system thinking with user thinking. Know precisely what happened, but shift to your user’s perspective. Explain what they need to know in terms they understand. Otherwise, obscure warnings like LaTeX’s “underfull hbox (badness 10000)” will result.

Users seeing a diagnostic will want to know two things:

What precisely happened to cause the error, in terms from the product’s ontology? This should help them know the impact of the failure and provide clues as to how to remediate it.

What can they do about it, if anything? Actionable diagnostics will directly help them accomplish their task.

Let’s tackle those two goals one at a time. But first, let me introduce an example that will thread through the next few sections.

Case Study Introduction

Channelz is a fictional software as a service (SaaS) company building a workplace communication tool like Slack, Microsoft Teams, or Discord.

Elise works on the API team, and her teammate Deng is the tech lead.

In Channelz, one can write direct messages to coworkers or send them to “channels,” which are groups of employees organized around a specific topic; the API engineering team might have a channel called #team-api-eng. Elise’s user handle is @elisek and Deng’s is @deng.

Channelz is building out an API that can be used to send messages from bots, either directly to users or to channels. Their customers want to use it to send various notifications.

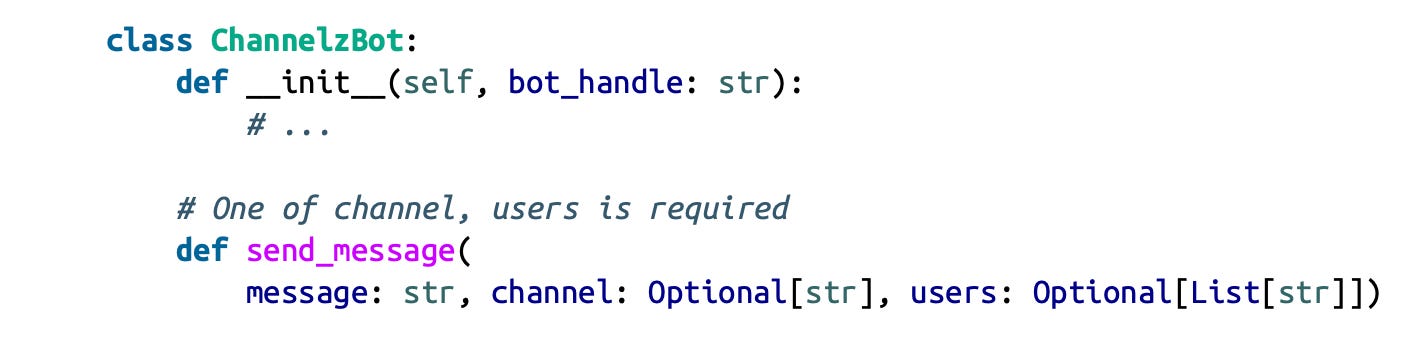

Before coding, Elise sketches a quick developer interface design and shows it to Deng. Channelz messages can go to a set of individuals or to a channel to alert employees when something has gone wrong or a job has been completed.

The method in the Python SDK they ship to customers will look like this:

She sketches some use cases for Deng:

Deng looks at Elise’s design and asks her to list failure scenarios as well. Elise has shown successful usages of the API, when callers already know what to do, but what about before then? If their users’ coding session is a journey, Elise has shown only the end. It’s as if somebody asked for directions with an online maps search, and she responded with only a pin on the destination.

Elise comes up with a few scenarios. (I will teach probing for edge cases in Chapter 7. For this chapter, I’ll skip that step.) She raises one important scenario that we’ll obsess over here: what if the user or channel passed into the API is invalid?

[We now skip ahead to the middle of the chapter, skipping through the section titled Provide Context.]

Make Error and Warning Messages Actionable

In many circumstances knowing what happened is only half the battle. Users often need to be given suggestions or told what to do. And for read operations—and increasingly with AI—you can even correct the mistake for them, as with Google’s “Showing results for: [correction]” feature, as well as coding or writing assistants automatically fixing your code or language.

We’ve all spent countless hours of our lives dealing with error messages, figuring out what to do, sometimes discovering after much investigation that the fix is simple.

In this section, you’ll see how to routinely improve your diagnostics. To achieve this, you’ll need to empathize with your audience, starting with the scenario categorization we did previously.

Returning to our Channelz example, suppose you called the API:

bot.send_message(message=”The sky is falling!”, channel=”@barnyard- friends”)

and got this error message:

Cannot deliver a Channelz message to channel ‘@barnyard-friends’: channel does not exist.

Can you tell what went wrong? It may take a bit to figure out, and if you’re not super familiar with Channelz nomenclature, you may not realize that channels are prefixed with #, not @.

It would be better to give our users a couple of options for what to do:

Cannot deliver a Channelz message to channel ‘@barnyard-friends’: it is prefixed with @. Did you mean to pass it into ‘users’? Or did you mean ‘#barnyard-friends’?

Channelz could even query accounts to see if #barnyard-friends exists—and is public to the user—and show:

Channel @barnyard-friends is prefixed with @, but we found a channel, #barnyard-friends. Is that what you meant?

By eliminating chunks of “search space” for your users, suggesting actions can save hours or prevent them from giving up and churning out of your product. Even a simple “try again in a minute” after a System error can increase completions of workflows.

Sometimes, the advice gets complicated. You may need to introduce users to some concepts, like the concept of channels, or guide them through a number of decisions. Where appropriate, link out to documentation dedicated to resolving that error. For example, if this case were more complex, you might do:

See https://channelz.io/docs/errors/invalid_channel to learn how to resolve this error.

Raise Errors at the Interface

If it were straightforward to write good error messages, engineers would do it more often. One of the main reasons they don’t is because it often takes diligent code organization to pull it off.

To write the best error messages, you need two pieces of information: What happened in the system? And, what was the user trying to do? The trouble is, in real life a different piece of code has each piece of information.

One place, near the API or UI boundary, knows who the user was and what they were trying to do. It is best placed to tell the user what to do without mentioning implementation details the user won’t be aware of.

The other, deep in the bowels of your processing code, is where the problem happens.

This came up when we were categorizing errors. When we divided by zero, Python’s division operation knew the exact law of mathematics being violated, but had no idea how the division was being used and therefore no hope of giving a good error.

The best place to raise errors is usually at the interface between the system and the user, where we can combine the bottom-up and top-down knowledge. (An alternative is to pass all the user context down, which I’ll explore in a later section.)

Generally, people raise at the interface in two ways:

They raise errors proactively, using upfront validations at the API boundary.

They use error handlers to intercept a lower-level error and repackage it into an appropriate form.

To illustrate each, let’s return to Channelz.

Upfront Validations

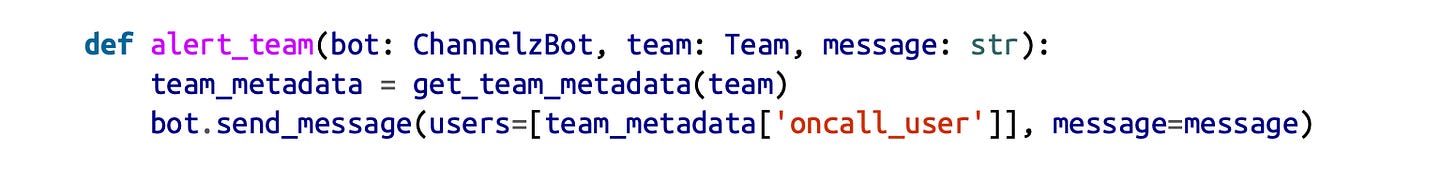

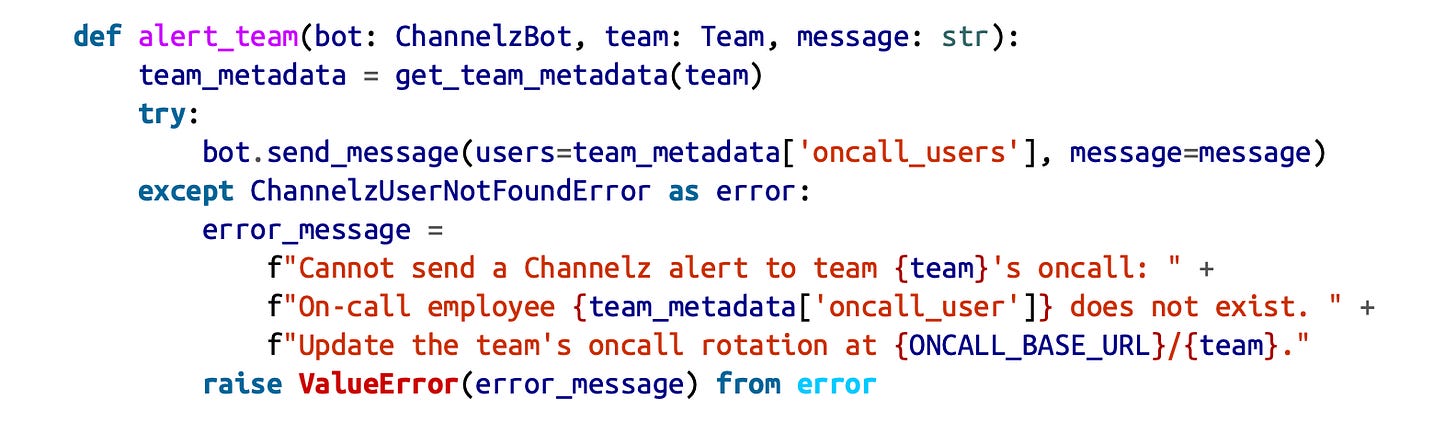

The Observability team at ChickenLittle has another problem. The function powering their on call messages is alert_team:

get_team_metadata reads a database of on call rotations that people at ChickenLittle set in a user interface at https://corp.chickenlittle.io/oncalls/.

What happens if team_metadata[oncall_user] is invalid? Recall that send_message will raise this error:

Error: Cannot deliver a Channelz message to ‘[@gooseyloosey]’ because ‘@gooseyloosey’ has been deactivated.

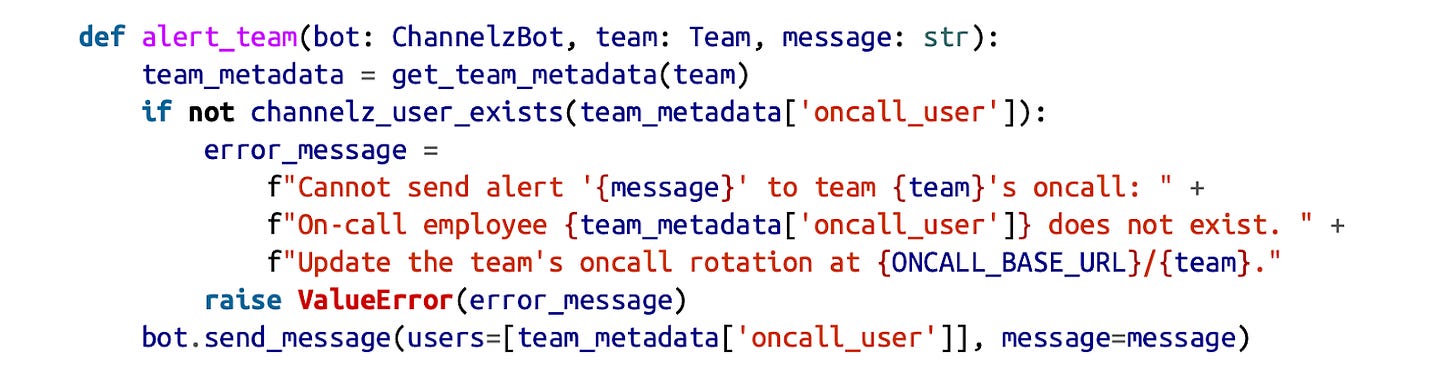

This is accurate, but when Goosey Loosey left the company, users couldn’t figure out how to fix the problem. So the Observability team added a validation upfront to tell folks what to do:

When a user is missing, this method is here to help:

Cannot send a Channelz alert to team ‘barnyard-friends’. On-call user ‘@gooseyloosey’ does not exist. Update your oncall rotation at https://corp.chickenlittle.io/oncalls/barnyard-friends.

This higher-level API alert_team captures the intent of the caller much more completely than send_message, which is a powerful basis for providing great errors.

Tip: Throw errors from the outermost layer of your API or application code where you can capture the user’s scenario.

The approach of upfront validation did the trick here, but it wasn’t perfect. Can you spot any issues?

Let’s look at an alternate technique of repackaging errors that your dependencies raise and see if it works any better.

Repackage Errors

There were two problems with the upfront validation. It’s expensive—it uses an extra roundtrip with the Channelz API. More important for our purposes in this chapter, the validation would need to duplicate edge-case-checking code already being done inside the Channelz API, such as checking whether @gooseyloosey’s account was deactivated. That info is still actionable—suppose the employee changed their Channelz handle because they changed their name. That would warrant a separate fix.

Since she’s given such good support before, the Observability team complains to Elise. They would rather write something like this:

Notice the from error clause in the last line. This is Python’s way of expressing “chained exceptions,” which preserves the inner error. Many programming languages have similar mechanisms. This would be the output:

ChannelzUserNotFoundError: User @looseygoosey’s account has been deactivated.

The above exception was the direct cause of the following exception:

ValueError: Cannot send a Channelz alert to team ‘barnyard-friends’.

On-call employee ‘@looseygoosey’ does not exist.

Update your oncall rotation at https://corp.chickenlittle.io/oncalls/barnyard-friends.

This is a longer message, but it contains everything the user might want to know. Observability asks Elise for specific errors in Channelz’s SDK so that they can do this.

With all these employees leaving ChickenLittle, Elise hopes the sky is not falling over there for her favorite design partner. Then, she and Deng investigate making their exceptions more programmable.

Since we’re diving into programmability, I’ll end our discussion of actionability and raising diagnostics from the interface layer here, turning my attention to making errors actionable for developers and their users.

[We now jump to the end of the chapter, skipping sections Raise Programmable Errors, Raise Specific Errors, Group Errors According to Scenario Category and Keep Information Around for Diagnostics]

Diagnose Early

Giving early diagnostics is often called shifting left and has numerous benefits for the system and for users.

Tip: Shift left. Give diagnostics to your users as early as you can.

For the system, it reduces resource usage by cutting off useless code paths. This can be critical, for example to fend off denial-of-service attacks. It also protects that same code from processing unpredicted inputs, preventing bugs like data loss.

Users benefit even more. Erroring early saves them time—think about how much time you save getting an error in your IDE rather than when deploying to production. Also, users are more likely to remember what they did when they get quick feedback, and to be more certain of the right action.

Here are four common techniques for shifting left:

Do static validations

Validate upfront

Let them test

Request user confirmations

Engineers widely practice the first two, but unfortunately not the last two. I came here to evangelize them all.

Do Static Validations

When validating any input, static validations can be performed cheaply and without deep inspection or network calls, while dynamic validations require more work or context.

Tip: Separate your cheap checks from your expensive ones and do the cheap ones early and often.

Many programmers are familiar with the pleasures of static typechecks and linters, but this comes up in products, too.

For example, when taking user input in application forms, look for cheap ways to tackle the users’ most common mistakes early, and provide inline advice telling them what needs to be corrected. Postal codes can be verified to be of the right length for their countries. Credit card numbers, UPC codes, and ISBN numbers have built-in checksum digits that help protect against common errors like typos and transpositions. These techniques shift left and also provide more certainty to diagnoses. If the checksum fails on a number, we know it’s not just missing from our database—it’s just flat wrong.

Validate Upfront

When I talked about crafting errors at the surface of an application or API, upfront validations provided a tool for more actionable and understandable error messages. But validations are also a tool for shifting left.

Imagine you went to the laundromat to wash your clothes, and you washed them, only to discover that only one dryer was online and it was booked for hours. A sign on the door would have saved you from a lot of wet, moldy clothes!

Similarly, when moving money, it’s essential to validate that the destination account is valid before withdrawing it from the source account.

Multistep workflows like laundry, money movement, and money laundering often benefit from upfront validation.

Let Them Test

If there’s one set of user scenarios I see most often neglected by platform engineers, it’s testing. They think of customers successfully using their production product without considering the trials their customers go through to get there.

If you’re building a developer service, your customers will adore you—and you’ll get adopted faster—if you build a fake. Fakes are high-fidelity versions of production systems that share as much code with the production path as possible, while taking certain shortcuts to avoid flaky runtime dependencies such as databases and online services that would make tests slower and less reliable.

Channelz should build a fake service for their messaging API. It would ideally:

Run in-memory or in a lightweight local process so that it can be tested by its users in their test environments and locally on their development machines

Allow users to input a bunch of users and channels so that they can then test various pieces of code that use the API

Act just like the production service for as many scenarios as possible

For a real-world example, Stripe, a provider of payment and billing APIs and UIs, provides a popular “test mode” in which one can do realistic transactions without actually moving money around. For example, customers can pass in special credit card numbers to induce various Invalid User Argument and Precondition errors. The card number 4000 0000 0000 9995, for example, simulates a card_declined error with an insufficient_funds subcode.

Stripe users spend far more time with test mode than with production, leveraging it when writing integration tests and testing user interfaces. For example, if a merchant wants to test their credit card input form, they can plug those magic numbers in manually and see how the site behaves.

Fakes are great ways to shift errors far to the left—to before developers even get properly authenticated or submit a production request.

Request User Confirmations

Confirmations are roadblocks in your app or platform that help users verify whether they have done the right thing. They are louder than warnings but not as intrusive as errors.

They frequently appear in user interfaces and developer tools when heuristics detect something odd about the user’s input. They explain why it might be unexpected or dangerous, and provide the opportunity to correct it or confirm it.

Google’s “Did you mean” is a fine example. When a user searched for “compture,” maybe they really were referring to Compture, the band. So, Google can’t just return an error, but they can report their suspicion to the user upfront rather than relying on them to figure it out after digging through search results.

Or instead, when you have just asked a user to fill out several pages of forms, show them a summary of what they’re about to submit so they can check for errors.

Confirmations allow you to shift left at times when you can’t be certain that the user is wrong without running the input through the whole system, but you can take your best guess.

One common method to allow upfront testing is with a “dry run” followed by a confirmation. In a stock-trading app, this is as simple as multiplying the number of shares someone plans to purchase by the current share price to show users how much they will spend.

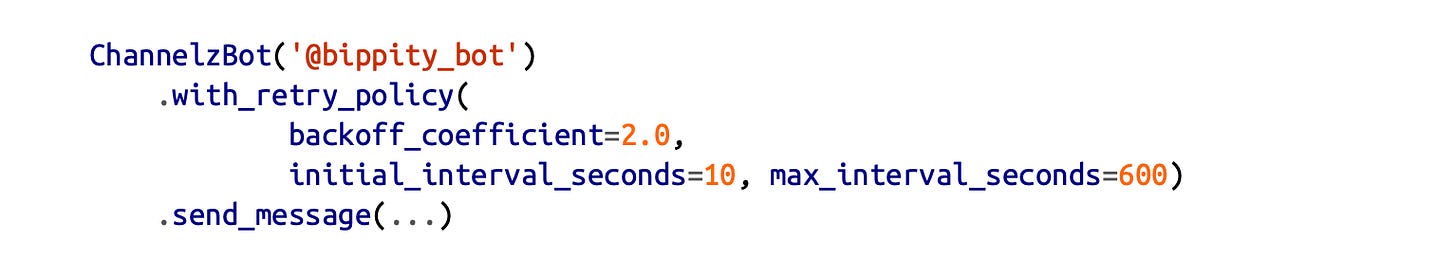

Here’s a more complex dry run at Channelz. Suppose Elise wants to add retry policies to her API, designed to be used like so:

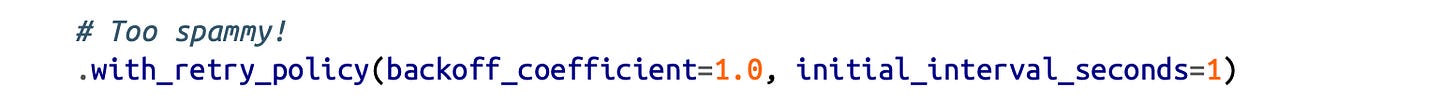

What happens if ChickenLittle authors a really spammy retry policy that retries once a second, forever? This could cause an accidental Denial-of-Service (DoS) style attack on Channelz, which would surely result in ChickenLittle’s traffic being throttled.

Elise could shift left with a heuristic-driven warning by simulating the retry policy and flagging bad behavior:

Your retry_policy (currently initial_interval_seconds=1, backoff_coeffi cient=1.0, max_attempts=Infinite) will result in 601 attempts in 600 seconds. This exceeds our limit of 50. You may ignore this by adding .ignore(Errors::RetryPolicySpamminess) to your policy.

Elise is not perfectly confident in her exact heuristic, but she can move fast and help her users out by providing this sort of confirmation that stops development temporarily. If her heuristic is off, users will complain, and she can adjust it upward.

In developer tools, --force flags override confirmations.

Confirmations aren’t foolproof—users might blithely confirm or copy/paste a -- force flag. So don’t use them for inputs you really can’t accept. That said, most developers I know are accustomed to absolutes—either the input is allowable, or it’s not. You’ll find that thinking about a middle case—the input is probably wrong—unlocks an incredible amount of richness and expressiveness in your interfaces.

In this section, we discussed the merits of shifting left and captured some of the many user scenarios that would benefit from the practice.

Since shifting left sometimes means we can’t perform a full, perfect validation, I explored techniques such as service fakes, heuristic-based confirmations, and static validations like checksums to address the most common user mistakes as early as possible.

Chapter Summary

As you think about writing your next few diagnostics, start by shifting your focus to your users’ experience and consider what they know, what they need to know, and what they should do. If you’re writing an error, bucket it into its scenario category— System, User’s Invalid Argument, Precondition, Developer’s Invalid Argument, or Assertion. This will help you to reason about constructing the metadata and message.

In your messages:

Give context. In most cases, echo back the operation being done and the bad data that was passed in.

Use concepts from the product’s user-facing ontology.

Suggest actions, and be willing to suggest alternatives if there’s not just one.

You’ll be more likely to do a good job of all of this if you raise the error to show the user from the interface boundary. For developers, include enough context and structure with your error so that other developers can do their jobs. Organize your errors into hierarchies to provide developers with both generic and specific ways to serve their users.

Finally, find creative ways to shift left for common or important scenarios, such as via techniques like confirmations, static checks, and fakes.

Exercises

Search the web for “Windows Blue Screen of Death Evolution” and watch as a few decades of Windows teams struggle to improve their error messages. (a) Decide which personas its messages are tackling. (b) Later in the video, you’ll see the Windows 11 screen. Analyze its message for the personas you picked.

For the next questions, pretend that you work on an e-commerce app. Users can fill their shopping cart and check out. The app finalizes orders via a submit_order API with the following fields: user ID, shopping cart ID, and credit card CVV code—the three- or four-digit code to verify a credit card. Your mobile client has the ability to do static verifications before sending up data to your API.

What error scenario category are invalid user ID and invalid shopping cart ID?What error scenario category is an invalid CVV code?

What about an empty CVV code?

Write an actionable end-user-facing error message for a missing CVV code.

Shopping carts can expire and are automatically deleted from the system after 24 hours. What scenario category of error is raised when the user tries to resume their session by adding to a deleted cart?

Can you think of a way to shift this expired shopping cart error left so that the user doesn’t need to re-find each item?

Takeaways

That concludes the excerpt

Many thanks to Drew and O’Reilly for sharing this extract from the new book. I very much recommend it if you’re interested in strengthening your “product muscle” as a software engineer, and it comes with lots of actionable examples. You can subscribe to Drew’s Substack, follow him on LinkedIn, and read more about his personal journey to becoming a product-minded engineer. Drew is also a speaker at the upcoming The Pragmatic Summit.

(or get it on Amazon)

What I really appreciate about the excerpt is that Drew goes into detail about the significance of those parts of a product which devs rarely think of, such as simple things like error messages. With well-crafted errors/warnings, you can reduce confusion, improve a product’s usability, and improve “stickiness” (i.e., when users “stick around” with a product despite it having issues).

My sense is that being a product-minded engineer is more than a simple checklist of skills, but I appreciate that Drew breaks down the important areas to focus on, like using your own product, collecting customer feedback, understanding users, understanding the product better, its architecture, and more.

I’m unsure to what extent 20+ years of lived experience can be captured in a single volume, but Drew makes a superb effort at doing so. In your own workplace, if there are standout product-minded engineers – or developer-minded product managers – from whom you can learn tips and tricks, then this book may seem familiar. For the rest of us, “The Product-Minded Engineer” is a great introduction to becoming a product-minded software engineer at a time when demand for this role is rising alongside the rapid growth of AI in our dev workflows.

Thanks, Gergely, for posting, and thanks to everyone for reading and sharing!

I didn't write this book because of AI--many of the topics, like errors and warnings, I've been itching to cover for years. But the AI transition *is* likely why it was chosen for publication. This is a very nervous moment in the history of software engineering as the role gets redefined, and amid all the fun engineers are having coding with Claude et al., I think individual contributors feel anxiety--am I ready for what's coming? As a lifelong IC, and in the spirit of Kent Beck's mission to "help geeks feel safe in the world," I hope this helps.

I want this to be a dialogue, not just a book. I'd love to hear from folks on Substack or LinkedIn--stories, questions, topic suggestions, or feedback about the content.

@drew Definitely getting this book. Would love for you to analyze more real world use cases (the Stripe example of using test more than production was a very interesting example).

Also really liked the exercises.