Why techies leave Big Tech

A job in Big Tech is a career goal for many software engineers and engineering managers. So what leads people to quit, after working so hard to land these roles?

Hi – this is Gergely with the monthly, free issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. If you’ve been forwarded this email, you can subscribe here.

In case you missed it: the first two The Pragmatic Engineer Podcast episodes are out: Efficient scaleups in 2024 vs 2021 and AI tools for software engineers, but without the hype. Each episode covers approaches you can use to build stuff – whether you are a software engineer, or a manager of engineers. If you enjoy podcasts, feel free to add it to your favorite player.

Ask a hundred software engineers what their dream company is and a good chunk are likely to mention Google, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, and other global tech businesses. This is no surprise:

Brand value – few businesses in any sector are better-known than Big Tech

Compensation – pay is usually at the very top of the market. Ranges can get especially high in staff-and-above positions. We cover more on pay in The trimodal nature of tech compensation and in Senior-and-above compensation in tech

Scale – infrastructure used by hundreds of millions or billions of users, data storage measured in petabytes, and services which handle requests at the thousands per seconds, or above

With upsides like these and others, why walk out? To learn more, I asked several software engineers and engineering leaders who did precisely this. Personal experiences vary, but I wondered if there are any common threads in why people quit prestigious workplaces. Thanks to everyone who contributed.

In today’s deep dive, we cover:

Big Tech less stable than it was. Big Tech had few to no mass layoffs for years – but that’s all changed.

Professional growth in a startup environment. It’s hard to keep learning in some Big Tech environments, compared to at startups.

Closed career paths at Big Tech. It’s often more achievable to get to executive-level engineering positions at scaleups, than at global companies.

Forced out. The bigger the company, the more there’s politics and scope for workers to be victims of competing interests, personalities, and rivalries.

Scaleups get “too Big Tech.” Scaleups are nimble and move fast with few processes. Successful scaleups slow down and add more process.

Steep compensation drops. A falling stock price can make people consider leaving if it leads their compensation to also reduce. Also, when an initial equity grant vests out after 4 years.

Raw feedback. A former engineering leader at Snowflake shares their take on how people leave workplaces – or struggle to; golden handcuffs, a Big Tech hiring slowdown, a bifurcated market, and more.

1. Big Tech less stable than it was

Luiz Santana was a tech lead manager at Google in Germany, before leaving to cofound the health tech startup, Digitale Patientenhilfe. Before Google, he was a senior engineering manager at fintech N26, and head of engineering at ride-sharing app, FREE NOW. Luiz shares why he decided to say farewell to what looks like a techie’s dream job:

‘Some things helped me make the decision to leave Google:

The startup I got an offer from had raised healthy funding, meaning a good amount of runway

I managed to negotiate to join as a cofounder and CTO, which meant a healthy equity package.

The other two cofounders have a great track record with a previous startup. This gave me confidence.

‘Google changed a lot, which also made the decision easier:

Google had layoff tension at the time. In mid-2023, there were lots of small, unpredictable layoffs, which made Google feel less of a “secure” place to work.

The culture also changed visibly. There was cost cutting, ranging from small things like reduced snack selection, to some teams having trouble securing servers they needed for organic growth.

I realized I am no fan of promotion-driven culture, which I saw to result in outcomes I didn’t like.

‘Google makes it hard to leave. Some big factors held me back from quitting:

Compensation. The biggest challenge, by far! Google pays very well, and few if any companies can match the total package. In my case, I received my stock grant at half the stock price to what it was vesting at. This meant that my equity compensation was already worth double!

Brand. I have always been a big fan of Google products, and being associated with Google is a big positive in so many ways.

Risk. Staying at Google is lower risk – even with layoffs – than joining a startup is.

‘Personal circumstances made the decision to quit easier.

I had “layoff fatigue” keeping track of all the small layoffs in various teams.

In Germany, I was at higher risk of being laid off because I was not married at the time and do not have kids. There’s a “social criteria” for redundancies in Germany, and I was not in a protected bracket; if a layoff happened, I was a prime candidate.

I trusted the founders, and appreciated that they spent a lot of time with me, sharing their vision.

‘After a lot of back-and-forth, I finally pulled the trigger to join the startup. I’ve not looked back since!’

Luiz’s hunch about diminished job security echoes the reality. Since mid-2022, Big Tech has shattered its image for job security:

Meta let go ~25% of staff in 6 months in two separate layoffs. Before November 2022, the company had never done mass redundancies; then it did two.

Google never did repeat annual layoffs in its history until in 2024, following shock layoffs in 2023

Amazon made deep cuts in 2023. The company is also known for less job security due to using PIPs more than most other Big Tech companies. PIPs are used as part of meeting unregretted-attrition targets

Microsoft did large cuts in 2023 and small layouts since

Tesla did widespread layoffs in secret in 2022, hitting long-time employees with a 1-week severance package.

Apple and NVIDIA are the only two Big Tech companies not to do mass layoffs in the last two decades.

2. Professional growth in a startup environment

Benedict Hsieh is a software engineer based in New York City, who spent five years at Google, before quitting for a startup in 2015. Ben describes his journey:

‘I didn’t want to become a ‘lifer’ at Google. This was the specific reason I left Google: I felt I was headed in a direction of being stuck there for life. I was only learning Google-specific tech, and the position was not very demanding. I felt like I should be working harder and learning to create value on my own, instead of only functioning as a cog in the machine.

‘I’d stopped “exploring” and was mostly “exploiting.” There is a mental model I like called the explore-exploit tradeoff. Exploitation means you choose the best option based on your current knowledge. Exploration means you try out new technologies and approaches. Reflecting on my day-to-day work, it felt that almost all of it was “exploiting,” and I was doing very little “exploring.” It was too early in my career (and life) to stop exploring!

‘I think my mentality of worrying about not doing enough “exploring” is rare. Almost all my former peers are still at Google because the total compensation is really, really hard to beat!

‘Looking back, I was overconfident about how quickly I would grow in startup-land – both professionally and in the financial sense. I was willing to take the hit on significantly decreasing my total compensation, and getting a larger chunk of startup equity. I was impatient about hitting my “retirement number” by joining a fast-growing startup with much higher upside.

‘Also, to be frank, I figured that I could go back to working at Big Tech anytime I wanted: because I spent enough years there, and had a pretty good existing network.’

Ben joined a startup as a cofounder. The experience was not what he expected, as he wrote about:

‘I was miserable. We were working out of [my cofounder’s] unfinished apartment which was freezing cold in the middle of the winter and a constant reminder of all the things that weren't going well. I'm a low-conflict person who needs hours to calm down after an argument, where she preferred communicating via loud debate.

‘I was trying to learn all kinds of things that we needed for our business – how to work with clients, keep our servers up at all hours by myself, debug statistical anomalies in our data, or send out cold emails to find new business. I was the only one who could do these things, so I got them done. I woke up early in the morning and had trouble sleeping at night. Once I worked past midnight to compile a report for a client who'd requested a last-minute meeting in the morning, only for them to no-show, followed by an email two days later asking me why I hadn't found another way to send them their data. If I had asked my body what it wanted in that moment, it surely would have responded with incoherent screaming. It basically did that without being asked.

‘Our company folded in less than a year.

‘But in eight stressful and mostly unpleasant months I accomplished more than I had in the eight years before that. We made some money for our clients, and a minimal but nonzero amount for ourselves, and I was able to parlay the experience into an early position at a much more successful startup. More importantly, I learned how to just get things done when they need to be done, instead of feeling like a helpless bystander watching a car crash.’

Ben reports that the new startup he is working at is doing a lot better, and reckons he needed a “startup shock” to develop his professional skills beyond the (comparatively) neat and tidy confines of Google.

3. Closed career paths at Big Tech

A product manager based in Seattle worked in Big Tech for 14 years: 3 at Amazon, and 11 at Google, where they went from a product manager on a single product, to senior product manager, group product manager, and product lead for a portfolio of products. Despite promotions into influential positions, they quit the search giant for a fintech startup, as VP of Product. They asked to remain anonymous, and share:

‘I'd already decided to quit Google without a new gig lined up. This was because I couldn't find a new role that was a combination of interesting challenge, interesting people, and/or one that fulfilled my career goals. I had over 50 conversations inside Google for ~9 months.

‘I talked to many ex-Googlers and ex-Amazonians during interviews. I'd never heard of my current company prior to joining, but most people I met during the interview were ex-Googlers/Amazonians. They were tackling the worthy, difficult problem of building a truly modern fraud monitoring and management platform.

‘This company isn't a remuneration leader by any means. "Closing" a candidate – them accepting an offer – is a combination of:

A strong “sell” during interviews

Showcase the concentration of world-class talent at the company

Highlight that the team ships very fast – much faster than Big Tech!

Articulate interesting technical and product challenges the team overcomes

‘Despite not knowing about them, it turns out this business has a strong brand in the banking software sector. They have established business moats, and the more I learned, the more impressed I was.

‘The company is in the middle of an organizational turnaround that I get to be an active part of, as a VP. This challenge appeals to me because I get to work with a really motivated set of people who are focused on making a big difference within the company, but also across the financial industry.’

This journey from Big Tech middle-management into leadership at a scaleup, makes a lot of sense. Making the jump from engineering manager or product lead, to an executive position, is close to impossible at Big Tech because the change of scale is vast. An engineering lead might have 10-50 reports, but a VP or C-level will oftentimes have 10x more. There are exceptions, of course, like Satya Nadella, who rose through the ranks at Microsoft, from software engineer, through vice president, to CEO. But in general at large companies, getting promoted to the executive level is formidably difficult. Scaleups offer a more achievable path to C-level.

At the same time, tech professionals with managerial experience in Big Tech are often perfect fits for senior positions at scaleups. Recruitment like this can be a true win-win! A new executive gets to learn a lot by getting hands-on with strategy, attending behind-the-scenes meetings, liasing with the board and investors, and many other experiences that are simply off limits at Big Tech.

In exchange, the scaleup gets a seasoned professional who doesn’t panic when facing decisions potentially involving tens of millions of dollars, and who can make correct, well-informed decisions – which is what Big Tech managers do, usually.

4. Forced Out

Working at Big Tech is far from perfect; the larger the company, the more organizational politics there is, some of it bad.

Justin Garrison, former senior developer advocate at AWS, felt this after he posted an article that criticized the company, entitled Amazon’s silent slacking. In it, he wondered if Amazon’s sluggish stock price was the reason for its strict return to office (RTO) push, and whether it was a way to quietly reduce headcount via resignations. Justin shared other observations in the article:

“Many of the service teams have lost a lot of institutional knowledge as part of RTO. Teams were lean before 2023, now they’re emaciated.

Teams can’t keep innovating when they’re just trying to keep the lights on. They can’t maintain on-call schedules without the ability to take vacation or sick days.

The next logical step to reduce costs is to centralize expertise. It’s the reason many large companies have database administration, network engineering, or platform teams.

They’ll have to give up on autonomy to reduce duplication. Amazon has never had a platform engineering team or site reliability engineers (SRE). I suspect in 2024 they’ll start to reorg into a more centralized friendly org chart.”

Justin’s team was also hit by layoffs: his team was eliminated, but not his role. He was left in a limbo state of needing to find another role within the company, and was not offered severance. Justin suspected Amazon was aiming to avoid paying severance packages, and incentivised managers to put engineers on a performance improvement plan (PIP) and let them go without severance.

In the end, Justin didn’t want to go through what he predicted would be a demotivating, unfair process that would end in him being fired. So, he quit.

Afterward, he joined infrastructure startup Sidero Labs as head of product, building what they aim to make the best on-premises Kubernetes experience.

Ways out of Big Tech manager conflicts

There’s a saying about quitting that “people don’t leave bad companies, they leave bad managers.” It contains a kernel of truth: a bad manager is often reason enough to leave because it’s the most significant workplace relationship for most people.

At large companies, there is an alternative: internal transfers. As an engineer, if you feel held back by your manager or team, you can attempt to move. Internal transfers are usually a lot less risky– as someone changing jobs – than interviewing externally. With an internal transfer, you get to keep your compensation and network inside the company; in fact, you grow it. Also, your knowledge of internal systems and products is valuable.

There are usually a few requirements for an internal transfer to happen:

Minimum tenure: internal transfers are open to those at the company or in their current team for a year or more.

Good standing: performance reviews which meet expectations are needed to get to move, usually. This is to avoid low performers escaping to switching teams. Being on a performance improvement plan (PIP) is a blocker to moving at most companies.

Other teams’ headcounts: internal transfers can only happen when teams have the budget for your level. Internal transfers are a way to hire more efficiently.

Pass an interview: at many companies, internal transfers go through an internal interview. This is usually a lot more lightweight than external ones. The process usually depends on the manager. It might be a simple chat and review of your existing work, or be more competitive if there are other candidates. For example, at Microsoft/Skype, when I changed teams as a developer, my new manager had internal candidates do a software architecture interview.

Get approval from the existing team. At some places, this can be a thing! An existing manager can slow down a transfer, or even sometimes veto it. However, in practice, if an engineer and manager have a poor relationship but the engineer has decent standing, then the manager doesn’t have much reason to block their departure. Of course, a manager may be able to make the situation challenging enough that seeking opportunities externally seems like the better option.

5. Scaleups get “too Big Tech”

An engineering leader spent four years at Snowflake after joining in 2019, right before its IPO. They’ve asked to remain anonymous, and share why it was time to depart the data platform:

‘Snowflake became “too Big Tech” for my liking. When I joined, there was a lot of uncertainty within the company and teams moved quickly. We had to make rapid changes, and four years later, things looked different:

Stable teams

Mature and well-documented processes

Lots of internal committees

Ever-growing amount of documents

Endless program management work before starting anything meaningful

Lots of politics! Cliques formed and there was “empire building” in upper management.

‘I have to admit, none of this is for me; I’m more of a “move fast and build things” person. At the same time, I acknowledge that many people felt very comfortable with these changes, and thrive in them!

‘The reality is that the company became successful, quickly. I enjoyed being part of the ride and helping create this success, but the change in culture made it feel less close to me than the “old” culture.

“Working at a scaleup that became “Big Tech” made it so much easier to leave! I’m certain that having Snowflake on my resume gave me a huge head start on someone equivalent from a medium or lower tier company. If I didn’t have Snowflake on my resume, recruiters would have skipped over me, and hiring VPs would be extremely skeptical.

‘So while there have been lots of changes in culture thanks to the standout success of Snowflake, it gave a lot of career options to me and everyone who helped build Snowflake into what it is today.’

6. Steep compensation drops

Big Tech compensation packages usually have three components:

Base salary: the fixed sum in a paycheck

Cash bonus: awarded at the end of the year at some companies. Netflix is among the companies which do not award bonuses

Equity: awarded as an initial grant that vests over 4 years, usually. Most Big Tech companies offer equity refreshers

The more senior a position, the more of the compensation is in equity. Tech salary information site Levels.fyi maps how Microsoft’s positions offer considerably more equity, and how principal-and-above engineers usually make more in equity per year than in salary:

Rising stock prices make it hard to hire away from public companies

Equity is converted from a dollar amount to the number of stocks on issue date. This means that if the stock value increases later, so does the grant value. If the stock goes down, so does the grant value, and total compensation with it.

This connection is why it’s close to impossible for a company to tempt NVIDIA employees to leave the chip maker, if they joined in the past four years and are still vesting out their initial grants: NVIDIA stock is worth 10x today than 4 years ago. So, let’s take an engineer who joined in October 2020 with a compensation package of $250K per year:

$150K base salary

$400K in equity (vesting $100K/year on the issue date)

Four years later, this engineer’s 2024 total compensation is around $1.15M, thanks to stock appreciation:

$150K base salary

$1M in equity vested in 2024 (thanks to that $100K/year grant being worth 10x, $1M/year!)

Falling stock price: big incentive to leave

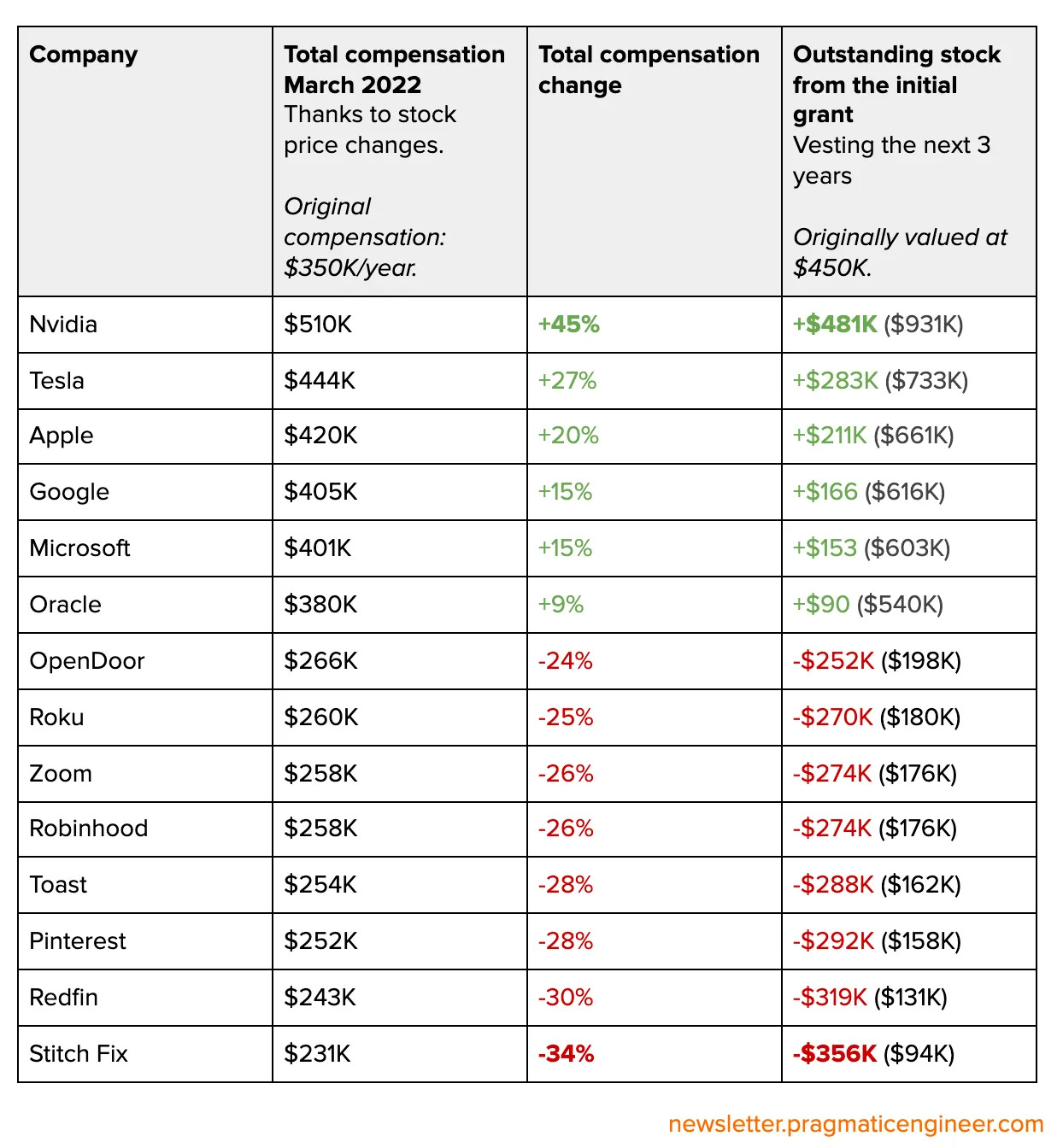

Stock prices don’t only go up, they also go down; and when they do the equity value of comp packages drops significantly. We previously covered how low stock prices lead more people to leave listed tech companies in May 2022. From The Pulse:

Some tech stocks have had a terrible past 12 months. Here are some of the tech companies which have seen their stock prices decrease the most since a year ago:

Stitch Fix: -79% 📉

Redfin: -71% 📉

Pinterest: -65% 📉

Toast: -64% 📉

Robinhood: -61% 📉

Zoom: -61% 📉

Roku: -60% 📉

Opendoor: -56% 📉

Docusign: -48% 📉

In comparison, some Big Tech have done well:

Nvidia: +107% 📈

Tesla: +63% 📈

Apple: +47% 📈

Google: +37% 📈

Microsoft: +34% 📈

Oracle: +20% 📈

Let’s take a senior software engineer who offered a $350K/year package in March 2021. Let’s assume they got this compensation package at all of the above companies, and that the package consisted of:

$200K cash compensation (e.g. $170K base salary, $30K bonus target)

$150K/year stock compensation ($600K in stock, vesting over 4 years).

Here’s what their compensation would look like, assuming no cash compensation changes:

Back when these stock drops happened, my suggestion was this:

“If you’re an engineering manager at a company where the stock has dropped significantly: buckle up for a bumpy ride. Unless your company can deploy significant retention grants, you will likely see record attrition in the coming months. Make cases for these retainers, but know that companies have financial constraints: and this is especially the case if the stock underperforms for a longer period of time.

If you’re looking for a new position: at places that issue equity, you’ll need to take a bet on the trajectory of the company. Consider companies where you believe in the company, their products, and how those products will grow over the next several years.”

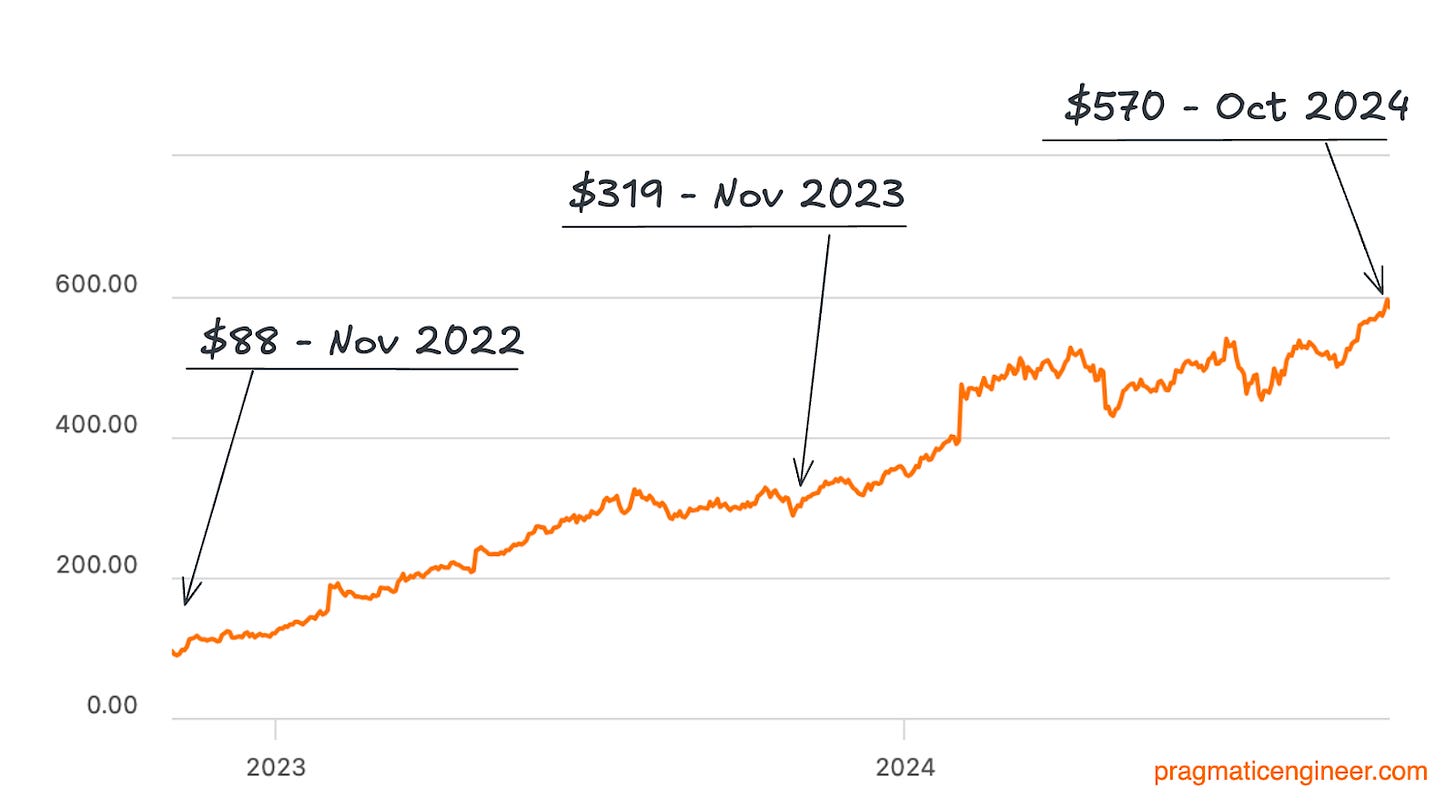

Over time, Big Tech stock has done much better than many recently IPO’d tech scaleups. The biggest stock drop happened at Meta, at the end of 2022. In just 6 months, the company’s stock price dropped from $330 to $88 – a 70% drop! Everyone who joined before 2022 saw their stock grants lose 50-70% of value on paper. Recovery was uncertain:

That year was probably one of the best times ever to hire away from Meta, due to its reduced stock price dragging down overall compensation. From early 2023, Meta’s stock rapidly recovered; employees’ issued with stock in 2022-2023 have seen its value multiple. From a total compensation point of view, it’s again hard to hire away from Meta:

We covered equity refresh targets per level in the US in Inside Meta’s engineering culture.

Four-year cliff

An event that frequently reduces compensation is the four-year vesting cliff, when the initial equity grant runs out at Big Tech. At senior engineer-and-above, and engineering-manager-and-above positions, these initial grants can be significant. It’s not uncommon for more equity to vest per year during the first four years of the initial grant vesting, than total compensation. The problem is that when this initial grant runs out, the compensation drops because the company does not “top up” with a similarly generous grant. This can mean a 10-40% drop in total compensation – pretty demoralizing!

As a manager, I dealt with the problem of engineers hitting 4 years’ tenure, and their annual earnings dropping 25-30%. The same happened to my own compensation package: in year 5 at Uber, I would have made about 30% less than in years 1-4, due to the initial equity grant running out, and lower annual refreshers. In the case of Uber, the stock price stayed relatively flat, and the drop in pay was the difference between revised compensation bands, and the equity which joiners had managed to negotiate.

Some Big Tech companies make the “cliff” less steep. Speaking with an engineering leader at Meta, they told me the annual refreshers offered at L6-and-above levels (staff engineer equivalent and above) are usually large enough to ensure no major compensation drop.

However, there are also companies like Amazon where only top performers receive top-up equity. This means that after four years, those without equity awards see a major compensation drop, as the compensation then only comprises salary, as Amazon doesn’t do cash bonuses. When this happens, it’s a signal that Amazon doesn’t particularly want to retain someone. It’s common for engineers to start applying externally when their equity is set to run out.

When a company’s stock price keeps increasing, the 4-year cliff becomes more painful. In Big Tech there are compensation targets for every engineering level. People earning above this target get very little or no equity refreshers, as they are already above target.

Going back to the example of NVIDIA, and the imaginary software engineer on $250K/year in 2020 ($150K salary, plus $100K/year stock), who’s on track to make $1.15M in 2024, thanks to NVIDIA’s stock price increase. That software engineer could see their compensation drop from $1.15M in 2024, to $150K in 2025, assuming no further equity refreshers. Even with an equity refresher of $400K over 4 years, their compensation will still drop from $1.15M in 2024 to $250K in 2025!

As a tech worker, it’s easy enough to rationalize that current compensation is outsized compared to other sectors; but you don’t need to be psychic to understand that a pay cut is demotivating; people are doing the same job as before for less money.

Assuming our engineer managed to save most of their gains from the incredible stock run, they might have a few million dollars in savings. This creates room for taking a risk, such as:

Joining another company for higher compensation (very small risk)

Joining a startup for lower compensation package but more equity (moderate risk)

Cofounding a startup, taking a steep cut on compensation, but a high equity stake (high risk)

7. Raw Feedback

The engineering leader who left Snowflake for becoming “too Big Tech” interviewed with several startups, and is in touch with peers still working in Big Tech. They share some unfiltered observations about people considering leaving big companies

Golden handcuffs

'Golden handcuffs' are a big thing at companies like Snowflake. I know plenty of people who are still riding out significant equity grants from the last few years that increased several times in value.

‘Salaries have stagnated across the industry, though. Back at Snowflake, we hired some people who were overpaid, compared to the current market. I know this because I hired some of them! We offered above the market because in 2021-2022 we were desperate to fill positions, like everyone else!

‘This is the problem with golden handcuffs: when you are lucky enough to have them, it’s hard to find anywhere offering more because you’re already above the market bands! So the only way to avoid a compensation cut is to stay.

Hiring slowdown

‘I have seen a slowdown in hiring across the tech industry, mostly at bigger companies. It also impacted people at the “lower end” of experience and domain expertise. If you are a very experienced engineer or engineering leader, or have some specific skills/knowledge that is in demand, the market is good in 2024!

‘Non-listed companies are still hiring more than public ones. I’ve talked with a decent number of strongly-growing companies and most want to hire experienced people.’ This observation tallies with one from the deep dive in August, Surprise uptick in engineering recruitment

‘I’m an example of the demand for experienced people. I have not been actively looking for jobs – but out of curiosity, I made myself open to inbounds from recruiters on LinkedIn. In two months, I had interviews with engineering VPs for series C and D companies. I am actually going to NYC next week for a half-day onsite as the final step for one role with a series D. I haven't actually actively applied to any jobs while doing so!

Bifurcated market

‘The current job market seems to be divided into two parts:

Experienced folks: If you are a senior, experienced person, especially with in-demand skills, there are options and the market is still moving steadily, if a bit slower than before

Junior folks: if you are more junior, or don't have unique experiences or skill sets, you are probably not going to see many opportunities in the current market

Risk takers favored:

‘There are two types of people when it comes to taking risks:

Builders and risk takers: people who like to build and grow teams and programs, who like taking risks, and jumping into the unknown with a bit of chaos. I’m someone who thrives on that; I get bored easily!

Incremental improvers seeking stability. Many people like to run things and make incremental improvements, from one stable job to another stable job.

‘In the current environment, big and stable companies are not hiring so much. So the people getting jobs are willing to take risks with less predictable companies, and jump into some chaotic situations.

Tech industry becoming ‘tiered’

‘An article by The Pragmatic Engineer covers the ‘tiering’ of the tech industry, which I experienced at first hand.

‘At my job before Snowflake, I was around “mid tier” at a financial software company. I would have been stuck in this “tier”, but got lucky in that Snowflake was desperate to hire tons of people in 2019.

Joining Snowflake immediately catapulted me into a much higher compensated group. Beforehand, I did not appreciate how massive the gap is between mid and top-tier companies! But I’m torn about this gap. On one hand, I really appreciate the compensation and career options. On the other hand, it irritates me how insular, incestuous, and hypocritical this is.

‘The upper tier literally feels like an old European aristocracy – and I’m saying this as someone who lives in the US! People help out their buddies, and are extremely suspicious of anyone not in their ‘club.’ It’s eye-opening to see how many people jump from company to company, taking their buddies with them. They all make lots of money, while keeping it exclusive and making sure it stays that way.’

Takeaways

Thank you to everyone who contributed to this look into why successful tech workers quit the most successful tech employers. When I joined Uber in 2016, it felt like the best-possible place I could have onboarded to. Back then, Uber had very positive media coverage, was called the most valuable startup in the world, and was the quickest to scale up in history. And yet, when I joined on the first 1:1 with my manager, the question I got from this was:

“So, what are you planning to do professionally after Uber?”

It was day one at the world’s most valuable startup; why was my manager asking about what I’ll do after this job? He later explained this question was because he’d been in the industry long enough to know that 99% of people don’t retire at their current company, and he wanted to be a supportive manager for future career goals. So if someone told him they might try to do a startup one day: he would try to get them involved in projects where they can do more zero-to-one building. If someone said they would like to get to a VP of engineering role at a scaleup later, he’d try to help them grow into a people manager. Everyone eventually leaves even the fastest-growing scaleups, or the most coveted Big Tech.

A smaller group departs into retirement, more commonly at companies like Microsoft and Amazon, where some engineers spend decades. But most people leave for other companies.

I hope the half dozen accounts from tech professionals who left Big Tech provide a sense of why people decide the most prestigious workplaces in tech are not for them.

Working at Big Tech can make leaving it much easier. This is counterintuitive because Big Tech pays so well, and the biggest reason against leaving is the compensation cut – at least in the short-term. However, the high pay allows people to save up a nest egg much faster, which provides the financial freedom to do something more risky like joining a startup and betting that the equity package will grow in value, or just taking a pay cut to join a company with more interesting work, or which they are passionate about.

Some people never stop growing professionally. A common theme in these accounts is feeling stagnant; most people felt they weren’t growing or being challenged. Some left because of frustration about doing more administrative busywork and less building.

Working at Big Tech is often a final goal, but a job in this elite group of workplaces can also be a stepping stone for pursuing new ambitions. I hope these accounts shed some light on the decision-making process and serve as a reminder that engineering careers are also about the journey, not just the destination.

"‘The upper tier literally feels like an old European aristocracy – and I’m saying this as someone who lives in the US! People help out their buddies, and are extremely suspicious of anyone not in their ‘club.’ It’s eye-opening to see how many people jump from company to company, taking their buddies with them. They all make lots of money, while keeping it exclusive and making sure it stays that way.’"

What has happened is, when you have only one or two roles open, and they are important, you get a lot more defensive, so you only hire "sure shots", people you know, people for whom their social capital and network capital will mean they have an extra incentive to do a decent job.

This is more of an incentive to do good work and not burn bridges, which I don't see as a bad thing.

Hi Gergely, I have a writing process/workflow question for you. While reading this, I saw you linked to a prior post about how promotion driven development works.

I think there's a lot of great content throughout the years, so how do you know where this content lives, and how are you able to find it?