What is Old is New Again

The past 18 months have seen major change reshape the tech industry. What does this mean for businesses, dev teams, and what will pragmatic software engineering approaches look like, in the future?

👋 Hi, this is Gergely. I give one conference talk per year: this was the one for 2024. It’s my best attempt to summarize the sudden changes across the tech industry and what they will mean for the next few years of software engineering.

To keep up with how the tech industry is changing, subscribe to The Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter, where I offer ongoing analysis. Readers of the newsletter have received many of the insights in this talk months ahead of the presentation.

What is the underlying reason for all the sudden change is happening across the tech industry, and how is the software engineering industry likely to change as a result? I tackled these burning questions in my annual conference talk, “What’s Old is New Again,” which was the keynote at Craft Conference in Budapest, Hungary, in May 2024. If you were there, I hope you enjoyed it! This article contains the full presentation, slides, and summary. I do one conference talk per year, and this was the one for 2024.

If you have some time to spare, you can check out the edited recording below, which has just been published. Shout out to the Craft Conference team for the excellent video production, and for organizing the event!

Also, watch the video on YouTube, access the presentation slides, or watch the Q&A after the talk.

In this article, we cover:

What’s going on?

Why is it happening?

Impact of interest rates on startups

Smartphone and cloud revolutions

New reality

History repeating?

Q&A, slides and further reading. Access the slides here, and watch the Q&A here.

1. What’s going on?

The tech jobs market, VC funding, IPOs, and Big Tech have been heavily affected by the winds of change in the past 2 years.

Job market

The end of 2021 was the hottest tech hiring market of all time, as described in The Pragmatic Engineer:

“If you are a hiring manager who needs to hire, you’ll know what I’m talking about. There is a fraction of the usual volume of applications, closing is more difficult, and candidates ask for compensation outside target levels. You might have had people verbally accept and then decline for a better offer. A hiring manager on the market:

“Never before has it been this challenging, and in all regions. I remember seeing a heated market before in India a few years back. However, the current environment is many times magnified. We are seeing the same type of intensified competition in the US, UK, EU, Eastern Europe, South America... Heck, just about everywhere. We are predicting this to last late in the year.” – a tech company with offices on most continents.

Analyzing the situation back then, I outlined six factors causing that “perfect storm” in the jobs market which turned it into an employee’s dream.

Six months later in February 2022, the New York Times (NYT) ran an article coming to a similar conclusion that tech companies faced a hiring crisis. However, by the time the NYT noticed, the job market was already changing fast again…

April and May 2022 saw unexpected layoffs:

One-click checkout startup Fast went bankrupt overnight, a year after raising $100M

Klarna let go 10% of staff in an unexpectedly massive cut

Several other companies followed with cuts: Gorillas, Getir, Zapp (instant delivery,) PayPal, SumUp, Kontist, Nuri (fintech,) Lacework (cybersecurity,) and many others.

Fall 2022 saw the big cuts continue, with Lyft, Stripe, CloudKitchens, Delivery Hero, OpenDoor, Chime, MessageBird, and others slashing 10% of their jobs or more.

One thing connected many redundancies: they happened at loss-making companies, so were easier to justify than at businesses that were in the black.

But then profitable companies started making cuts, too. In November 2022, Meta let go 11,000 people (13% of staff) in what were the first-ever layoffs at the social media giant. A few months later, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon followed suit; creating the biggest spike in job cuts to date.

VC funding

Before 2020, VC investment in startups was rising steadily. Then in 2021, the pace of investment exploded; nearly doubling:

Since then, VC investment has steadily fallen. In Q1 of this year, it was at the same level as 2018!

IPOs

2021 was a standout year for public offerings, as a relative flood of tech companies floated on the stock market.

For a sense of just how many IPOs there were that year, here’s just a few of the notable ones:

GitLab (version control,) Rivian (electric vehicles,) Couchbase (NoSQL database,) Affirm (buy-now-pay-later,) Bumble (dating,) Duolingo (language learning,) Robinhood (trading,) Expensify (expensing,) Nubank (fintech,) Roblox (gaming,) Coinbase (crypto,) Squarespace (domains,) Coupang (e-commerce,) DigitalOcean (hosting,) Toast (restaurant tech,) Coursera (edtech,) Udemy (edtech,) Amplitude (analytics,) AppLovin (mobile analytics,) UiPath (automation,) Monday.com (project management,) Confluent (data streaming,) Didi Chuxing (ridesharing,) Outbrain (advertising,) Nerdwallet (personal finance.)

By comparison, there were precisely zero tech IPOs in 2022, and only three in 2023 (ARM, Instacart, and Klaviyo.) Little did we know at the time, but HashiCorp’s IPO in December 2021 was the last one for 18 months.

Big Tech

The tech giants did large layoffs in early 2023, which were justified with the claim they’d overhired during the pandemic of 2020-2022. However, by the start of this year, Big Tech was still doing mass layoffs, despite not having overhired AND posting record profits. Google was the model case; founded in 1998, it had only done a single mass layoff back in 2008, when 2% of staff (300 people) were let go. Then in January 2023, around 6% of staff were let go. In January 2024, amid record revenue and profits, the search giant cut yet more staff:

Google’s approach looks pretty typical; regardless of record income and profits, Big Tech companies seem to have become comfortable with regularly letting people go.

I analyzed the rationale behind these cuts at the time, writing:

“Meta, Google and Amazon, are not cutting senselessly; they seem to be strategically cutting their cost centers and heavily loss-making divisions. Plus, they are very likely managing low performers out.”

Summing up

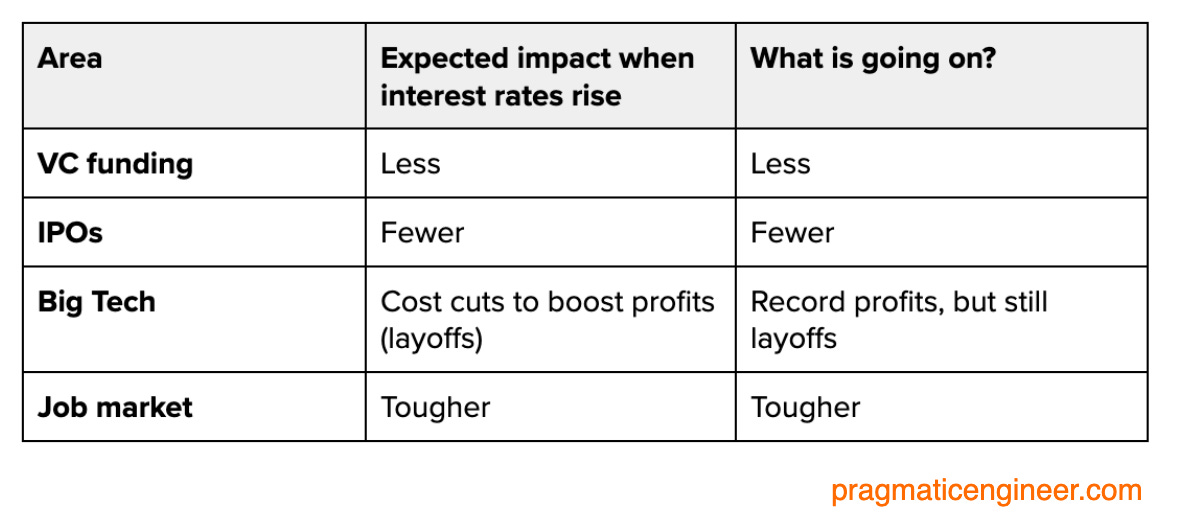

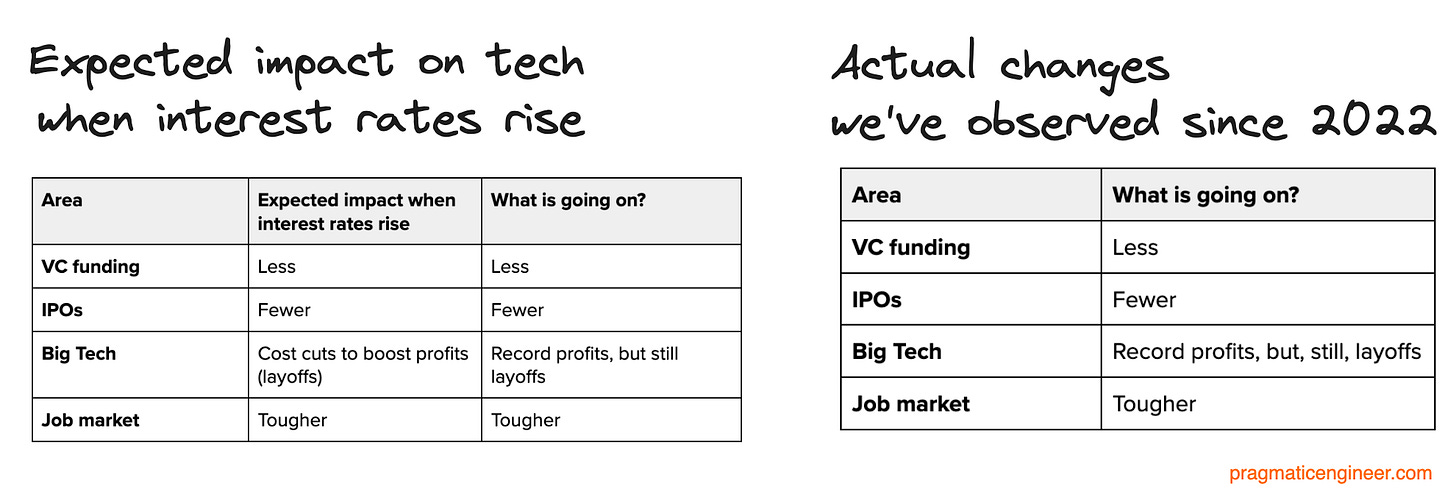

Here are the changes we’re seeing:

2. Why is this happening today?

Something changed around 2022-2023. But what?

An obvious candidate was the end of the pandemic and lockdowns of 2020-2021, as the world slowly returned to normal.

At the time, founders and CTOs told me why their companies were cutting staff, and why their businesses suddenly faced growth challenges. The “macroeconomic environment” was repeatedly mentioned and was echoed in company announcements reporting job cuts. It became clear that changing interest rates had a larger-than-expected role.

In mid-2022, the US Federal Reserve (FED) did something not seen in decades by increasing interest rates dramatically:

What are interest rates, and why are they going up?

We need to take a brief but necessary detour to understand interest rates a bit.

I refer to “interest rates” as the rate set by national central banks. In the US, this is the Federal Reserve (the Fed,) in the UK it’s the Bank of England, and in the EU it’s the European Central Bank (ECB.) These institutions aim to maintain financial stability with a mandate to execute governmental fiscal policy, which may be to increase or decrease consumer spending, increase or decrease inflation, etc. One of the most powerful “levers” a central bank has at its disposal is to set the interest rates that apply to deposits and debts.

In 2022, inflation was at a 40-year-high in the US (9.1% in July 2022), a 30-year-high in the UK (8.6% in August,) and at its highest-ever in the EU (9.2% in 2022.) Governments in these places set fiscal policies to try and pull inflation down to around 2-3%. The Fed, Bank of England, and (ECB) all took the same action: they raised interest rates.

How do higher interest rates slow down the rate of inflation? Here’s an explainer from the BBC:

“The Bank of England moves rates up and down in order to control UK inflation - the increase in the price of something over time.

When inflation is high, the Bank, which has a target to keep inflation at 2%, may decide to raise rates. The idea is to encourage people to spend less, to help bring inflation down by reducing demand. Once this starts to happen, the Bank may hold rates, or cut them.

The Bank has to balance the need to slow price rises against the risk of damaging the economy.”

Replace “Bank of England,” with “Fed,” or “ECB,” and it’s the same. Raising rates is a tried-and-testing method for tackling inflation, worldwide.

Why do higher rates matter?

In the US, the interest rate jumped from almost 0% to around 5% in less than a year:

To understand whether this rate change was “business as usual,” let’s look back 15 years or so:

This graph is eye-opening. Dating back to 2009, the interest rate was close to 0%, and then between 2017-2019 it climbed to around 2%. Then it promptly went back to zero due to the pandemic, as the Fed tried to discourage saving and encourage spending in order to stimulate the economy and avert recession.

Now let’s zoom out all way back to 1955 for a sense of what “normal” interest rates typically are, over time:

A “wow” point in the graph above reveals that ultra-low interest rates are historically atypical. Let’s mark up the periods when the interest rate was at or below 1%:

Since 1955, there have been a total of 11.5 years of ultra-low “near-zero” interest rates, 11 of which occurred after 2009. That’s why it’s known as a zero interest rate period (ZIRP.)

Interestingly, this ZIRP was not unique to the US. Very similar events played out in Canada, the UK, and the EU, due to the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007-2008, when the financial system had a near-death experience.

3. Impact of interest rates on tech startups

It’s tempting to assume tech is unconnected to finance and interest rates, but the truth is the opposite. This is not me saying it, but Bloomberg analyst and columnist Matt Levine, who’s passionate about the tech industry and explains how fiscal policies affect industry. In 2023, he analyzed the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank:

“Startups are a low-interest-rate phenomenon. When interest rates are low everywhere, a dollar in 20 years is about as good as a dollar today, so a startup whose business model is ‘we will lose money for a decade building artificial intelligence, and then rake in lots of money in the far future’ sounds pretty good.

When interest rates are higher, a dollar today is better than a dollar tomorrow, so investors want cash flows. (...)

If some charismatic tech founder had come to you [the bank] in 2021 and said ‘I am going to revolutionize the world via [artificial intelligence][robot taxis][flying taxis][space taxis][blockchain],’ it might have felt unnatural to reply, ‘nah, but what if the Fed raises rates by 0.25%?’ This was an industry with a radical vision for the future of humanity, not a bet on interest rates.

Turns out it was a bet on interest rates though.”

When I read this analysis, my instinct was to push back. Surely there could not be such a basic connection between interest rates and tech startups? However, the more I thought about it, the more I saw Levine had a solid point.

Let’s analyze what happens when interest rates rapidly increase from 0% to 5%, as they did:

Let’s also look at topics this newsletter covers, like VC funding, IPOs, Big Tech, and the job market, and how interest rates affect them:

Less VC funding: Venture capital is a high-risk/high-reward investment type that large pension funds and ultra-high-net-worth individuals invest in. The idea is to put a large sum, such as $100M, into a VC fund and wait around 10 years for a pretty handsome return. The investment might turn into $150M, $200M, and so on. The alternative is to keep it in the bank, but this erodes its value because annual inflation (for example, of 2%) reduces the purchasing power of a dollar, year on year. But with a 5% interest rate, you can turn $100M into $150M at virtually no risk; so why invest in risky tech startups – of which some succeed and some fail – and risk being left with less than the sum of your initial investment in a decade’s time?

Fewer Tech IPOs: Tech companies going public are generally loss-making, as they are still in growth mode; the majority of tech companies going public in 2021 were in this category. In a high-interest environment, investing in them is less tempting because unless they have a definite path to profitability: they could run out of money, thus devaluing your investment. Rivian’s market cap falling from $150B in 2021 to just $10B in 2024 – in part thanks to the risk of running out of money – is such a cautionary example. In contrast, investors can earn an attractive rate of interest by just putting their money in the bank, instead.

Big Tech profit push. During a ZIRP, the “baseline” return is 0%. When this baseline rises to 5%, profitable companies need a higher profit ratio in order to maintain their valuation. This means Big Tech cuts costs more aggressively in order to make their profits look better, even if already very profitable.

Worse job market. This is due to Big Tech layoffs and fewer startups hiring because there’s less VC funding available.

Let’s compare these with the changes of the past two years, as described in section 1 of this article; ‘What is going on?’

Comparing what we logically should happen with rising interest rates, versus what we are currently seeing:

It may be unexpected, but rising interest rates explain many trends in the tech market.

4. Smartphone and cloud revolutions

The drop in interest rates from around 2009 drove more venture capital into startups because VC investing is more attractive when interest rates are at rock bottom and the returns from government bonds are low. Two other factors also began to make an impact at around the time of the GFC.

Smartphone revolution

The iPhone launched in 2007 and the now-defunct Windows Phone followed two years later. Smartphones have transformed consumer tech, and were the catalyst for mobile-first tech companies, like Spotify (founded 2006,) WhatsApp (2009,) Instagram (2010,) Uber (2010,) Snap (2011,) and thousands more.

Cloud revolution

At around the same time as smartphones appeared, the first cloud providers launched:

2006: AWS

2008: Azure

2008: Google Cloud

Cloud providers made it much faster and cheaper for startups to build products. Instead of having to buy and operate on-prem servers, they could just rent a virtual server. And if they needed more capacity, they could just pay for it and scale up almost immediately. Early Amazon employee, Joshua Burgin, (now VP of Engineering at VMWare) described it in The past and future of modern backend practices:

“This [cloud] transition enabled early AWS customers like Netflix, Lyft, and Airbnb, to access the same level of computing power as established tech giants, even while these startups were in their infancy. Instead of purchase orders (POs,) months-long lead times, and a large IT department or co-location provider, you only needed a credit card and could start instantly!“

Some of the best-known AWS customers today are Netflix, Airbnb, Stripe, and Twitch. All grew faster – and likely needed less capital – by utilizing the cloud.

Overlap

The smartphone and cloud revolutions coincided almost perfectly with when interest rates fell to zero and then stayed in the deep freeze for a decade:

These developments gave VCs even more reason to invest in startups:

New categories of mobile-first startups were around, with potential to become billion-dollar companies if they moved fast. Raising large amounts of capital was crucial to win the market; Uber and Spotify succeeded with this strategy.

Startups could turn investment into growth more efficiently by throwing money at scaling problems by using the cloud, instead of spending years building their own infrastructure. This was another way VC investment helped startups win their respective markets.

It’s likely the 2010s were a golden age for tech startups, due to the ahistorical combination of the longest-ever period of 0% interest rates, and two technological revolutions which kicked off at that time.

Today, another potential tech revolution is heating up: generative AI, and large language models (LLM.) The AI revolution has similarities to the cloud revolution in how AI could also bring efficiency increases (once AI costs decrease from where are today.) However, the AI revolution is very different in nature to the smartphone revolution: this is because AI doesn’t appear to offer a new, initially free, broad distribution channel like the smartphone did for app makers. And the GenAI revolution also began in a high interest rate environment:

We cover more on the “how” of GenAI in these articles:

5. New reality

So, what is the “new reality” which we work in? Check out this part of the presentation for my take on what it means for software engineers and engineering practices.

Basically, it’s tougher for software engineers to land jobs, and career advancement is slower. For engineering practices, we’ll likely see a push to choose “boring” technology, monoliths become more popular, “fullstack” and Typescript gain more momentum, and more responsibilities “shift left” onto developers.

Previous newsletters go into even more depth:

6. History repeating?

Change is often unfamiliar and unexpected. Those around for the Dotcom Bust of 2001 must see similarities between today and the sudden changes wrought when the tech bubble burst, back then. Software engineers who were working during that period offer perspectives and tactical advice on how to prioritize career security when job security feels beyond control.

7. Q&A, slides and further reading

For a recap of the Q&A following the talk, see this recording.

Access the presentation slides.

I’ve covered several topics from my talk at length in individual analysis pieces. For more, check out:

Takeaways

Sometimes it’s helpful to “zoom out” and take stock of change as it unfolds across tech, in order to understand more about it. The demise of 0% interest rates is a mega-event with notable effects on the tech industry. It’s hard to predict the future – especially in tech, where things change fast – but I find it useful to seek understanding of the underlying forces influencing the direction of the sector.

From one perspective, the history of the tech industry is one of cyclical booms and busts. Innovation is fertile ground for new business opportunities, and I have no doubt there’s many boom times ahead; we just need to recognize them when they happen!

After the keynote, several people shared with me that it had “clicked” with them, in terms of their experience at work, at their friends’ workplaces, and on the job market. One participant said they’re planning their next career step, and understanding the trends at work is helping them to make more considered decisions:

“Using a soccer analogy: I want to run to the part of the pitch where the ball will be shot forward to, and not to where most players are looking at (where the ball currently is.) I feel I have more information about where the tech industry ‘ball’ will be headed in the next few years, so I can position myself better.”

I hope you found this analysis insightful, and the talk interesting to watch!

Finally, a big thank you to Craft Conference for hosting me. I asked the organizers how the conference did this year, and here are interesting statistics they shared with me:

2,000 attendees: around 1,500 in-person, and the rest online.

80 speakers: 95% of whom attended from abroad. This international roster attracted me to the event.

49 countries from which participants traveled, including Germany, Romania, Norway, Austria, the Netherlands, US, and Serbia, as well as locally-based professionals.

60% of participants were software engineers, 13% engineering managers/team leads, and 10% architects.

Javascript & Typescript are the most popular programming languages among attendees. Java, Python, C#, C+++, PHP, C, Go and Kotlin are next in popularity.

The event is annual and the next edition will take place in spring 2025.

Hey Gergely, amazing talk and article! This was really relieving to see. I think it would be interesting to go back to the ideas that were brewing around the post-dotcom-bubble era to see if there's more lessons to learn. I wanted to ask, in your talk you made a comment about how its an open secret that every company made their own NIH version of React Native. I'd love to hear more about that, and maybe some reporting about how the companies that have embraced React Native (Microsoft, Shopify, Amazon, Walmart) have been able to take advantage of the benefits. Thanks!

Thank you for gathering the data, analyzing trends, creating plots, and writing this analysis, Gergely! Your newsletter saves me a lot of time that I would otherwise spend doing these tasks to understand the software engineering industry. I appreciate that you explain the reasoning behind your conclusions so I can trace back to the data and understand both the outcome and how you arrived at it. It is very valuable!

So, GenAI is like the Cloud but with 5% interest rates? What would that look like? I don't have personal experience with the Dotcom era as I wasn't in the industry yet. However, I am familiar with the Cloud and am curious about how GenAI will differ. Can you write a post on this?